A great deal of ruin in a talent

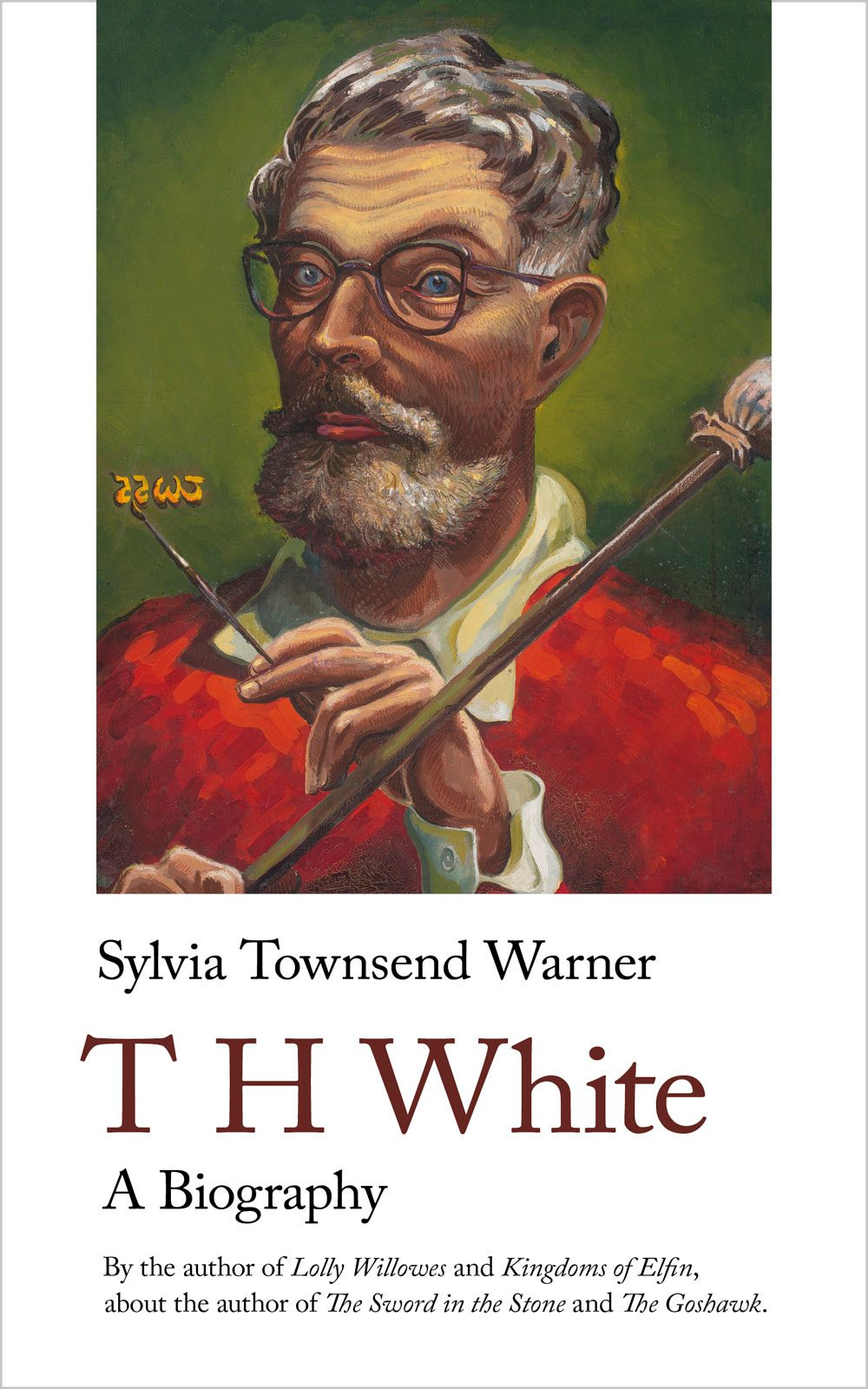

T.H. White by Sylvia Townsend Warner

What an interesting book this is, just reissued. Written by Sylvia Townsend Warner aged seventy (her first attempt at biography: late bloomer!) it was the first biography of White, written just after his death. White had a very mixed career. He’s know for only a few books now but he wrote twenty. He had many lives and lots of misdirection. He once complained of being idle like Johnson and wished he had a Boswell, on the assumption that Boswell did things like buy the tickets for their trip to the Hebrides. He drank too much. It’s a book, therefore, about a big talent that didn’t quite become a major one. Adam Smith thought there was a great deal of ruin in a nation and I wonder how often the same is true of talent.

As well as being a study of how much you might fail while you partially succeed, this books shows the way distractions can become inspirations. All that time spent lolling in pubs gave White an ear for folk dialogue. When he rather madly decided to train a hawk he became, as Warner nicely puts it, “the only twentieth century falconer to man a bird using methods Shakespeare would have accepted as traditional.” From this experience he later produced The Goshawk, his most successful work. It was White’s relationship with a dog that gave him the emotional breakthrough needed to begin the Arthurian series that became The Once and Future King. The ways in which we develop are not easy to predict. The best thing he ever did was to go and live feral (his word) in a cottage with a small clutch of animals.

Warner uses the technique of printing lots of letters and diary entries straight into the text without rewriting them into her own narrative. This is now often thought to be old fashioned and dull but Warner proves what a good technique it is. Whenever it is best to let the person speak for themselves, you should. Froude went to ridiculous lengths, once printing thirty pages of Carlyle’s notebook. Warner quotes with brevity, but not always with short passages. She lets White speak when he is interesting, when he describes something better than she can, when he is in some sort of mood. Her own prose is sharp too. She describes the red setter as having a “grieving Vandyke portrait expression.”

Warner doesn’t resort to psychology to explain White, rather she is prepared to speculate mildly with common sense about the sort of person he was. Here’s a typically clarifying moment:

If he had been committed to Wandsworth Jail, by the end of three months he would have been writing a history of Wandsworth, with sections on its geology, botany, bird-life, etc, together with a dictionary of prisoners’ slang and an analysis of what was wrong with the penal system and how to improve it. Wherever chance had directed him, his active, loquacious mind would have bourne him company… But at times one has the impression of this faithful mind looking up at the man and saying, ‘Master, why are you so sad, all of a sudden?’

I like that tinge of dualism, as if White’s mind were also his daemon. Warner is surely correct to compare this to his love of loyal animals and to note White had “complete control of neither.” This is, I think, the first time I have read a biography without reading the author’s novels first. I’m glad I did. It is so good it distracted me from my bacon and eggs.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

I love his writing in The Once & Future King. The animal, feral experience achieves such strangeness & power. And unbearable sadness. The hedgehog’s farewell.

Any similarities to J A Baker, The Peregrine?

I remember reading The Goshawk as a young boy and feeling transported to another world, full of magic and life.