A hanging and flogging sort of liberal. John Stuart Mill's support for the death penalty.

It is not human life only, not human life as such, that ought to be sacred to us, but human feelings.

The next book club is on 22nd October, 19.00 UK time. We are reading John Stuart Mill’s Autobiography. You can find the schedule here.

My final “How to Read a Poem” salon is on 9th November, focussing on Elizabeth Bishop.

The other side of the harm principle

John Stuart Mill is remembered for the harm principle: we should be free to do what we like, so long as we don’t harm others. This idea is foundational to modern liberal thinking and still debated today. But what about the other side of the harm principle? What did Mill believe should happen when someone did cause physical harm to another person? Despite the fact that Mill was a kind and gentle person, who meets every canon of liberal tolerance—Parliamentary reform, women’s equality, concern for the poor, religious toleration, penal reform, the importance of education, an interest in some forms of socialism—he advocated for harsh criminal sentences in a manner that might surprise us.

Mill thought that for “offences, even of an atrocious kind, against the person” the penalty was often “ludicrously inadequate, as to be almost an encouragement to the crime.” He even thought flogging, though generally “most objectionable”, would be a suitable punishment for “crimes of brutality… especially against women.” For crimes of violence, Mill wanted “severe sentences.” Prisons were too comfortable, too easy to escape from. Transportation had become “almost a reward” before it was abolished. And in limited cases, Mill supported the death penalty. John Bright, the Liberal MP, wrote in his diary how “deplorable” this was for a liberal like Mill—“many will be shocked.”

As we shall see, though, Mill’s case for the gallows was entirely consistent with his principles, even if it’s not with what we expect of him.

Mill’s support for capital punishment

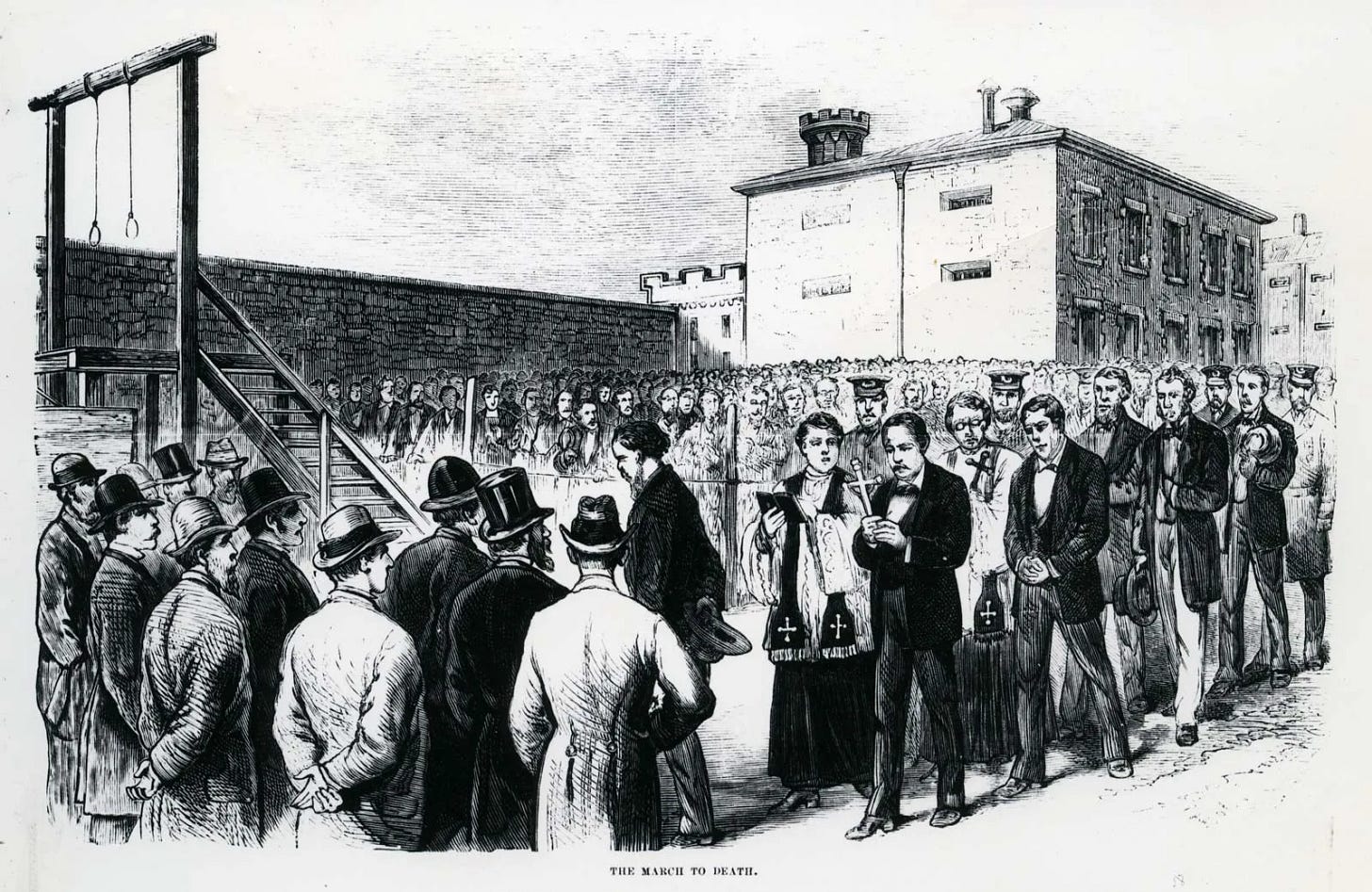

In April 1868, Mill spoke in the Commons on an amendment that would remove the death penalty from aggravated murder. This amendment was proposed by a group known as the philanthropists—a movement that had previously argued for the abolition of the slave trade, established children’s hospitals and orphanages, and campaigned to reform England’s penal code.

Normally, Mill would be on the philanthropist’s side. There was no group in public life he respected more. They worked with less “personal or class selfishness, than any other class of politicians whatever.” Mill remembered a time when people were hanged for stealing property worth forty shillings. It was the philanthropists who got that law changed, and others of “most revolting and most impolitic ferocity”.

But now was the time for their reforms to stop. Aggravated murder—murder with some additional evil: rape, robbery, premeditation, political motivation, racial or sexual motivation, the murder of a pregnant woman, and so on—was “the greatest crime known to the law”. Some of these criminals, Mill warned, show no remorse. Sometime there is “no hope that the culprit may even yet not be unworthy to live among mankind.” Sometimes the crime was not an “exception to his general character” but quite in keeping with it. These criminals could only be dealt with in one way: “solemnly to blot him out from the fellowship of mankind and from the catalogue of the living.”

How startling, to find in such a liberal person, the phrase, “the life of which he has proved himself to be unworthy.” These are the hard limits of Mill’s liberalism. Violent crime required strong deterrence, punishments that would approve themselves to the “moral sentiments of the community.”

Liberalism, death, and human feeling

Mill had no thirst for blood. His reasoning was rooted in compassion. The only alternative punishment, which could still act as a serious enough restraint, was life imprisonment with hard labour. Mill called this a “living tomb.”

What comparison can there really be, in point of severity, between consigning a man to the short pang of a rapid death, and immuring him in a living tomb…debarred from all pleasant sights and sounds, and cut off from all earthly hope

Considering most criminals will die not very much later, often with more suffering, Mill thought it probable that while the death penalty was “less cruel in actual fact than any punishment that we should think of substituting for it.”

Mill also saw value in the terrifying power the death penalty held on the imagination. In the future, he said, juries might shrink from finding criminals guilty, Home Secretaries might shirk their duty, out of a sense of horror at the punishment. If so, then the law should be reformed. Theft cases, under the old law, had become difficult to prosecute because people would perjure themselves rather than see a man hanged for such a minor crime. If that happened, though, Mill would see it as:

an enervation, an effeminacy, in the general mind of the country. For what else than effeminacy is it to be so much more shocked by taking a man’s life than by depriving him of all that makes life desirable or valuable?…

It is not human life only, not human life as such, that ought to be sacred to us, but human feelings. The human capacity of suffering is what we should cause to be respected, not the mere capacity of existing.

In our own time, the philosopher Derek Parfit has argued that all suffering should be avoided. Mill doesn’t go quite that far, but the question of human feeling is central to his argument, as it is to all of his work. As he wrote in Utilitarianism,

Few human creatures would consent to be changed into any of the lower animals… A being of higher faculties requires more to make him happy, is capable probably of more acute suffering, and is certainly accessible to it at more points… he can never really wish to sink into what he feels to be a lower grade of existence.

Mill didn’t think the death penalty was an affront to life, quite the opposite. “Does fining a criminal show want of respect for property, or imprisoning him, for personal freedom?” He thought England’s justice system more favourable to criminals than other countries. And he believed the harshness of the death penalty would make courts “more scrupulous.” Relaxing the punishment might reduce that scrupulousness, which would be a “great evil” to set against the potential errors of execution. And he conceded that the evidentiary standard ought to be raised.

Overall, Mill sees the death penalty as the least harmful option. He uses utilitarian principles, but with deep liberal concern for the quality of human life and the nature of suffering. That combination leads to his surprising conclusions. It is this ability to think, to apply principles to the reality of our times, that we should learn from Mill, more than any particular doctrine.

This was super interesting and admirably concise work; I feel sort of like Neo getting stuff downloaded into his brain when I read posts like this (your work offers that frequently).

Thoughtful and thought provoking piece. I get his point about death versus a truly unpleasant life. Does it ring true in today's world? I'm not sure that 'life imprisonment' is the horror now that it was then, or that the loss of freedom means the same, which tempers his argument a little. Perhaps. I like to think I am totally against capital punishment, but find myself momentarily wavering when the latest horrific serious crime hits the headlines. Then I settle back into complacent liberalism. It's a hard thing to talk about, thank you for approaching it through JSM.