I would not want to live in a society without gossip. Gossip is how we tell the truth. Most people, in social situations, are bad truth-tellers. Many nervous considerations stop us telling the truth in front of a group: you might not know how everyone will react; it might not be pertinent to them all, despite being salacious to them; you may feel awkward at the subject matter; it may rouse hostility; and so on.

But telling the truth is remarkably important. Imagine you consider going to work with someone, but they show signs of difficult behaviour. You will ask one or two people in private if your impression is correct. Is this person always like this? Do they get worse?

How ought these people to respond? Telling the truth is a moral good, and essential for true inquiry. But no-one wants (or says they want) to be a gossip. You may not consider this to be a paradigmatic case of gossip, but it is spreading unflattering information about a person behind their back:—Gossip often borders on a warning.

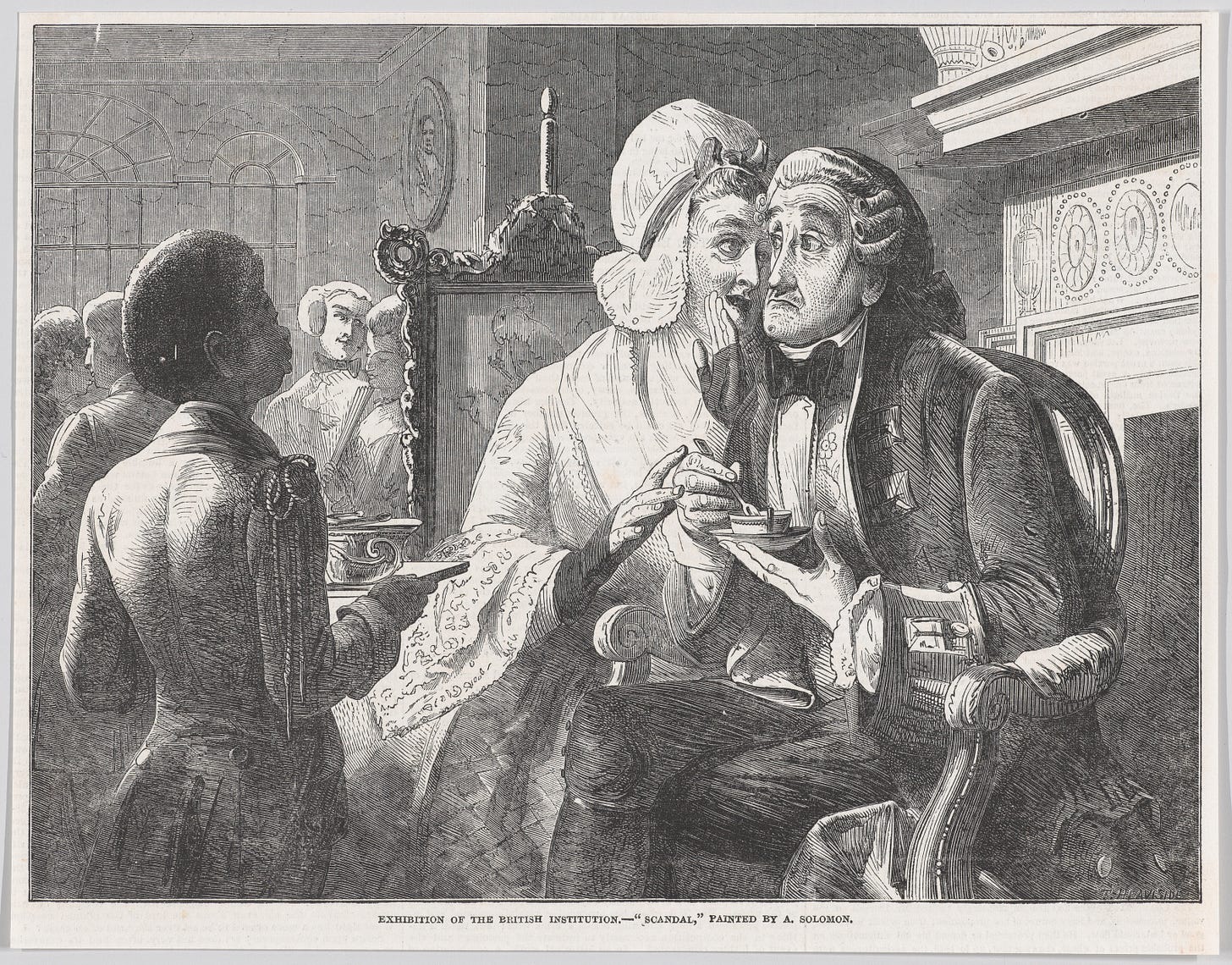

Johnson defined a gossip as, “One who runs about tattling like women at a lying-in.” A lying-in is the period of confinement during childbirth. So the gossip here is about paternity. He does not specify whether the information passed along is true or speculative, or whether it exists, like so much of what we think we know about each other, in between.

The OED defines the noun as “one who delights in idle talk; a newsmonger, a tattler.” A newsmonger and a tattler are not always so different as they appear. The scandal of gossip is often not that it is invented, but that is it true. It is a double scandal: once as it relates to the subject (they did what?), and once as it relates to the tattler (she told you that?).

In responding to the person asking to know if their new colleague is a bully, we are not running about tattling:—we are giving vent to our impressions without the chance to avoid judgement, ours or our interlocutors. The example is apt because it is a case of virtuous gossip: people should be warned before they work with bullies, even though, were they to hear of the warning, the bully might say, were you gossiping about me?

A lot of the gossip that I am told is not salacious, merely interesting. We all find great interest in the workings of other people. Well-intentioned and truthful gossip can be harmless, admiring, or a warning. If women were unable to gossip about men, they would all surely feel much less safe. If children were unable to gossip about grown-ups, they would find themselves more confused in their relationships with authority.

A far higher rate of women than men (according to survey data I can no longer find) report that before they consider accepting a job, they find someone they know (or someone who knows someone they know) inside the organisation. There are certain reassurances that can only provided in this way, which is a form of gossip. The news is passed on privately. Other people are implicated, judged, perhaps condemned.

Companies know this. “You brand is what they say about you when you leave the room” is a common marketing adage.

When gossip helps us find out the truths that we cannot discover more publicly it becomes a virtue. Talking about other people is another form of learning about other people. Done well, gossip is knowledge. Knowledge is essential to an ethical and intellectual life.

As Phyllis Rose wrote in Parallel Lives, “gossip may be the beginning of moral inquiry, the low end of the platonic ladder which leads to self-understanding.”

I started reading this with an expectation of disagreeing strongly with it, because (at least in my own head) I detest gossip and consider it pernicious.

But then I reached your comment about (mostly) women who "report that before they consider accepting a job, they find someone they know (or someone who knows someone they know) inside the organisation" - and I realized that I did exactly the same thing: before I accepted my current job, I spoke at length to someone who had previously worked there but had left about his experiences and his reasons for leaving. I didn't think of that as "gossip" ... but I suppose you're right, it was.

So ... I've had to rethink my anti-gossip position! I still believe that there is a huge danger of even truthful gossip being pernicious - in a previous job I experienced that, where I allowed my perceptions of some colleagues to be slanted negatively by things that other colleagues privately reported to me about them, which led to some very bad outcomes. But you're probably right that it can have more positive effects as well.

I had a boss who wanted to ban gossip in the office, which was ridiculous. It's how we bond with each other when you have little other in common than your place of work. Obviously her plan failed and we were subjected to many rants about how much she hated it in meetings. For many people it's what gets them through a job they hate.