Balloonmania

"it kindled in the air and was consumed in a moment"

1783-84 was the year of Balloonmania. “Balloons are so much the mode,” wrote the reclusive poet William Cowper from rural Buckinghamshire, “that even in this country we have attempted a balloon.” Explaining a trip he made to see an attempt to launch a balloon, he said, “The whole country were there, but the balloon could not be filled. The endeavour was, I believe, very philosophically made, but such a process depends for its success upon such niceties as make it very precarious.”

Flight was indeed a precarious thing, both a benefit and a curse. To James Woodforde, a Norfolk Parson, balloons were entertainment. In 1785 he recorded in his diary that he had seen a balloon flight persist despite a rainstorm. “A vast concourse of people were assembled to see it,” he recorded, noting that the man who flew the balloon was courageous to go up straight after such a tempest. Twenty years earlier, though, Samuel Johnson had anticipated the darker side of balloon flight.

“What would be the security of the good,” Johnson wrote in Rasselas in 1759, “if the bad could at pleasure invade them from the sky?” By the time balloons were launched Johnson was an old and dying man and decided they would be useful only for amusement, not communication or information gathering, “till they have ascended above the height of mountains.” Altitude is indeed what makes the difference to balloon technology. In recent years, the Pentagon has spent billions on high-altitude balloon development.

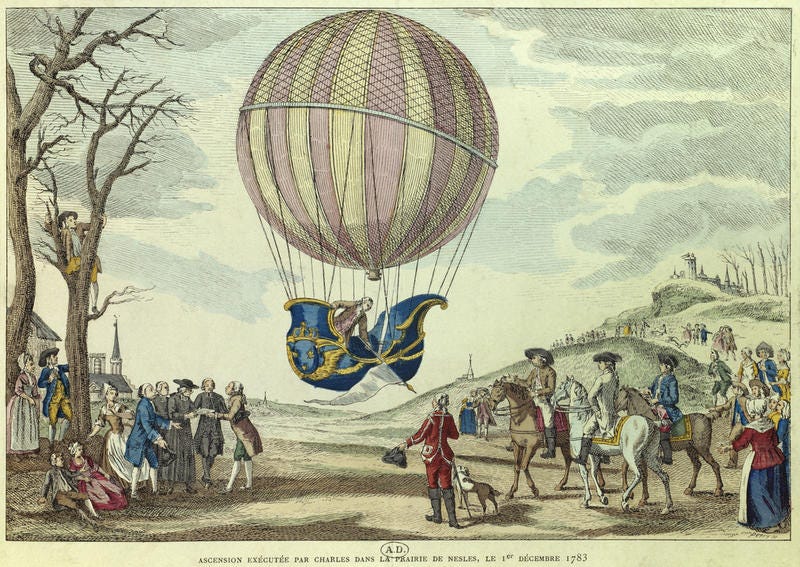

Montgolfier mania started in June 1783 when a balloon carrying a duck, a chicken, and a sheep was launched by the Montgolfier brothers at Versailles. In October, the first manned flight took off, supposedly in front of a hundred thousand spectators. In November, two experimental balloons were launched in London. They descended in the country and met quite different ends. One of them was hacked to bits by terrified peasants using pitchforks. The other was displayed by a farmer, who charged a penny to go into his barn and view the balloon. Toy balloons became popular and the new specialism of Balloon Maker was born.

Since the myth of Icarus, flight has been associated in literature with over-mighty ambition. Johnson’s remarks in Rasselas might have been inspired by Robert Cadman, a tightrope walker of Johnson’s youth, who died rope sliding across the River Severn. Johnson was never myopically literary—he was too interested in the mechanics of the world. To begin with, he wondered about ballooning’s potential to “bring down the state of regions yet unexplored.” Adventuring was part of the spirit of the age and scientific questions always fascinated Johnson.

Balloons did not fulfil their promise for Johnson, whose scepticism was married to his concern for his own health. “I had rather now find a medicine that can ease asthma,” he grumbled. Still, his curiosity never abated and he sent Frank to see the balloons take off in November 1784. One of the last things he wrote about balloons remains true today, as we have seen with our own balloonmania recently: “You see some balloons succeed and some miscarry, and a thousand strange and foolish things.”

Cowper, describing a balloon flight of August 1784, had a more foreboding tone, as you might expect from him:

On Thursday morning last, we sent up a balloon from Emberton meadow. Thrice it rose and as oft descended, and in the evening it performed another flight at Newport, where it went up and came down no more. Like the arrow discharged at the pigeon in the Trojan games, it kindled in the air and was consumed in a moment. I have not heard what interpretation the soothsayers have given to the omen, but shall wonder a little if the Newton shepherd prognosticate any thing less from it than the most bloody war that was ever waged in Europe.

That prognostication might still be extreme, but the most recent balloonmania is certainly a confirmation that we are in a new cold war. Like Johnson, unable to haul his infirm old body out to see the balloon, we are only experiencing this at second hand. We see the balloon, the video of the balloon, but it is not clear to most of us what it really means. “I see nothing; I must make my letter from what I feel,” wrote Johnson, “and what I feel with so little delight, that I cannot love to talk of it.”

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

A surprising read and a great way to put the latest balloon news into a slightly different context. Thanks!