Blue Ticket, Sophie Macintosh

A book review with statistics and graphs

Why is the population falling?

Did you know that car seat regulation is one of the reasons for the falling birth rate in America? Maybe you did. It’s not likely you’ve heard that more than once though, and probably recently. Far more possible is that you have heard repeated dozens of times during the last decade that the world is overpopulated.

The overpopulation claim is speculative, a hypothesis repeated as if it were a fact. The car seat claim is much more likely to be a fact. There’s empirical evidence that large car seats have a significant effect on family size.

The idea that we are overpopulated is also presented as an isolated idea; as if we could depopulate, regenerate the natural world, and expect no other side effects. Whereas, the car seat metric is fairly simple and uncomplicated, declining populations are not.

As Ross Douthat says in his excellent recent article,

The birthrate isn’t just an indicator of some nebulous national greatness; it’s entangled with any social or economic challenge that you care to name.

As social scientists have lately begun “discovering,” a low-birthrate society will enjoy lower economic growth; it will become less entrepreneurial, more resistant to innovation, with sclerosis in public and private institutions. It will even become more unequal, as great fortunes are divided between ever smaller sets of heirs.

These are just the immediately measurable effects of a dwindling population. They don’t include the other likely effects: the attenuation of social ties in a world with ever fewer siblings, uncles, cousins; the brittleness of a society where intergenerational bonds can be severed by a single feud or death; the unhappiness of young people in a society slouching toward gerontocracy; the growing isolation of the old.

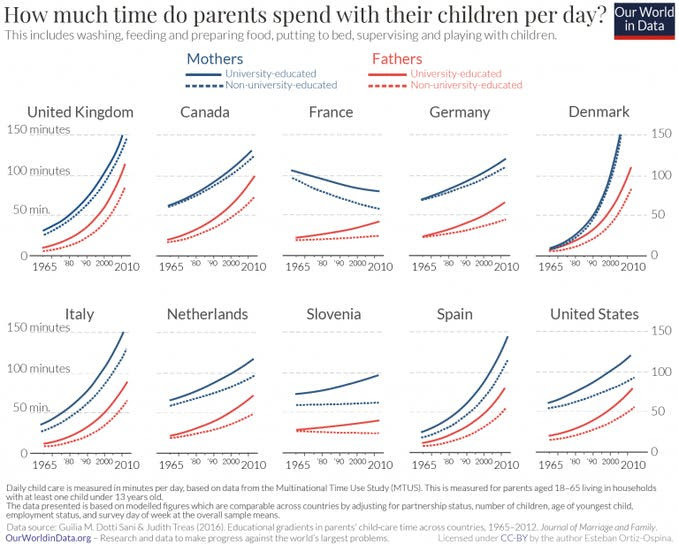

There’s some data amongst this debate that I think gets under reported. Parents today spend a lot more time with their children. You can read about that in Bryan Caplan’s book Selfish Reasons to Have More Kids, but this chart makes the point very clearly. The amount of time parents have spent with their children in the last sixty years has skyrocketed.

Is it so crazy to wonder that this has happened in parallel with falling birth rates and that it is not a coincidence? We realise that we are having smaller, more brittle families, and so we hold them closer. We saw our grandmothers and great grandmothers have five, six, seven siblings; we saw the generations shrinking; we felt ourselves getting more isolated. We did this at a time of rising wealth, so we coddled the children we did have.

Novels from the 1920s and 1930s are full of maiden aunts, a by-product of the war. The falling birth rate means novels of our time will soon be repeating the pattern. As Louise Perry says, in her wonderful article Why bother having babies?:

Around 18% of women in England and Wales born in 1972 reached the end of their childbearing years not having had children, compared with only 10% of women born in 1945. Millennials are projected to continue the trend. As of 2019, the total fertility rate in England and Wales is at a historic low of 1.7, and the Covid-19 crisis may lower that still further. All in all, it is quite plausible that at least 1 in 4 people of my generation will not be having children.

Finally, a novelist who can think, and use sentence fragments properly

You won’t find any graphs or statistics in Sophie Mackintosh’s novel Blue Ticket, but it is, as most good novels are, an exceptional thought experiment about an issue that isn’t as widely recognised as a potential disaster as it ought to be. (If you want data visualisation in a novel, read Helen DeWitt’s book of short stories Some Trick — link below — and pray she gets to finish and publish her next novel without being wittered away into oblivion by the publishing industry.)

You can think of it as a differently imagined version of The Handmaid’s Tale but more plausible, and focussed more on character than system. Not literally plausible — I don’t expect girls to be sent to the doctor to take a ticket that determines whether they are allowed to have children or not and then to be supervised by authoritarian state doctors for the rest of their lives. (Yes, that’s the premise of the book. The only other thing I need to tell you to get you hooked is that the protagonist gets a blue ticket (no children), realises she really does want children after all and goes on the run.)

I mean this book is plausible in the sense that there are a lot of women who are not having children under something that is neither choice nor the illusion of choice. In this case demographics is reasonably close to destiny.

Danny Dorling, professor of human geography at Sheffield University, describes the sharp distinction:

“Society has split into two groups. One group, of women graduates, clustered particularly in London and the commuter belt, is having children very late and the rest are having them at much the same age as their mothers and their grandmothers did.”

This first group of highly educated people, both male and female, is also the group most likely not to have children at all. In contrast, working-class people are more likely to hold on to traditional family values that include a disapproval of voluntary childlessness. In our society, blue tickets are not picked by lottery, but they’re not exactly randomly selected either: there are strong demographic forces at play, with class being the most important one.

Whatever causes the opt out, it happens. A belief system that having children is bad for the planet is a strong social enforcement mechanism. By the time you factor in class, not wanting to trade in a lifestyle, and the moral pressure not to ignore David Attenborough, there’s a case to be made that conformism is happening more than we realise, whether or not a doctor is enforcing it.

And conformism haunts the characters in this book. Every woman with a blue ticket has to go to her doctor regularly for a check-up. This is as much a surveillance check-up as a medical one. When the protagonist goes on the run she ends up in a kind of thriller plot, not knowing who she can trust.

And, finally, here is a writer who knows how to use sentence fragments. And she has saved the poor, abused comma. Blue Ticket is a blessed relief from the copywriter’s favourite literary style that has dominated so-called literary fiction for the last few years. It’s as if all novelists learnt how to write short prose from the same advertising agency.

This, however, is a fragmentary syntax that matches the slightly eerie, slightly familiar setting. Mackintosh said in an interview earlier this year, ‘I think you can do a lot with fragments; telling a story through shards.’ The book is also as free of political ideology as it is of reflexive, unthinking prose style.

This is because Sophie Mackintosh has a professional humility you don’t always hear from novelists. She talks about realising that while this is an important, under discussed, issue, ‘in the scheme of things, my book is just a book... there are a million takes one can have on any subject, and this is just mine. And to think of it in conversation with the others, perhaps, but finding its own way and interpretation.’

When was the last time you heard a writer talk so much like a thinker, rather than an aesthete? You don’t have to agree with the conclusions I suggested above when you read this novel. But it will engage with the arguments we are seeing in the data, through a plausible set of characters and circumstance. It will unsettle you.

Mostly, Mackintosh’s rare ability to think, to actually work through some of the implications of a situation, without adhering to an ideological bundle, will pull you along through her gripping, original story, that reaches a conclusion something like what she said about her own changing views on motherhood:

I had to study the narrative I’d built around myself, the narrative of who I was and what I deserved. What if having a child wouldn’t be a disaster? What if, actually, I was an imperfect person with a lot of love to give?… I saw more of my friends give birth around me, but also friends go through the heartbreak of infertility and miscarriage, I thought about how the desire to have a child was never that simple, nor that fair. And underneath it all I was thinking about the strangeness of existing in a body that seems sometimes to be working against your brain.

Read this book. It will grip you, challenge you, and stay with you.

Blue Ticket, Sophie Mackintosh (US link)

Some Trick, Helen DeWitt (US link)

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.