Carbuncular Karlo Marx

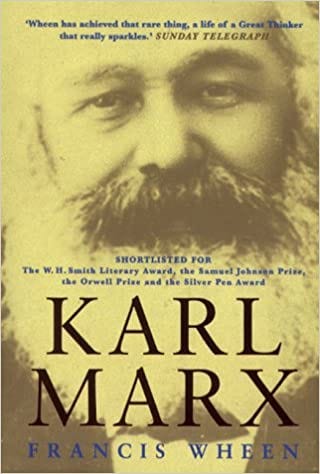

Karl Marx, by Francis Wheen. A witty, lucid portrait of an unexpected Communist.

Who would have thought a biography of Marx could be so entertaining? And not just because of the depressing fog of Marxism and its associated horrors that hangs over Karl Marx’s reputation and identity like an evil pea soup. Marx himself, at first blush, sounds pretty dull. He was a Hegelian who became a Communist and lived on smatterings of inheritance and stolen money (along with some journalistic earnings) in north London while he wrote a long, long book about the evils of being bourgeois. Hardly the makings of four hundred rip-roaring pages. No wonder we read so many books about characters like Churchill.

Groucho Marx once quipped, on one of many retirement Dick Cavett appearances, that there was always someone who thought one of the Marx brothers was called Karlo. In the late sixties when he made that joke, of course, Marxism was well on its way to the bottom. Now that we can look back at the man behind the ideas — who, it is easy to forget, was nothing to do with Marxism as it happened — it turns out he was a remarkably funny guy.

One of his ventures as a young man was a job as a newspaper editor. There was a jobsworth of a censor who had to check everything that was printed. This man was over zealous by nature, once banning an advert for the Divine Comedy on the grounds that ‘the divine is not a fit subject for comedy.’ Marx endured long sessions going through the paper word by word, line by line, persuading the censor that it was all harmless. This would go on into the night, leaving the printers waiting. For an editor with a deadline, this idiot of a censor presented quite a trial.

Karlo got his revenge. The censor had an invitation for himself, his wife, and his daughter to a swanky ball given by the President of the Province. That night, he had to edit Marx’s newspaper. Alas, he was left waiting, and waiting. By ten o’clock, no paper had appeared. Eventually he sent his wife and daughter to the ball and his assistant to the newspaper’s office. The boy came back saying the newspaper was closed.

So, the dutiful censor, anxious to get to his ball, scurried off to Marx’s house. By the time he got there, it was pushing eleven o’clock.

After much bell ringing, Marx stuck his head out of a third-storey window.

‘The proofs!’ bellowed up the censor.

‘Aren’t any!’ Marx yelled down.

‘But—’

‘We’re not publishing tomorrow.’

Thereupon Marx slammed the window shut. The anger of the censor, thus fooled, made his words stick in his throat. He was more courteous from then on.

If it weren’t for the fact that you know, on bona fides terms, that this was indeed the grand-daddy of Communism, this sort of antic would indeed be more typical of Groucho than Karlo. No wonder Francis Wheen describes Karl as ‘a bourgeois Jewish scallywag’ and called his unsuccessful novel Scorpion and Felix, ‘a nonsensical torrent of whimsey and persiflage.’

The whole book glimmers with this sardonic and defensive tone. ‘Only a fool could hold Marx responsible for the Gulag; but there is, alas, a ready supply of fools'.’ Wheen isn’t above ironic free-indirect style, either, describing Marx’s troublesome but put upon mother as, ‘his wretched mother.’ He also makes good material out of the fact that Marx was something of a Russophobe, but the book in which this is made explicit was missing from the official Soviet complete works of Marx.

The whole book moves at pace, so that even the descriptions of Marx’s works and studies are compelling. It would be easy for a biography of Marx to sink into the mud as soon as an exposition of his books was required. Not for Wheen. He can move smoothly from a two page discussion of how hairy Marx was into a neat description of the thesis and literary style of Capital.

It is easy to overlook the obvious, which may be why so few writers on Marx have noticed what is staring them in the face: that he was, like Esau, a hairy man… The image of Karl Marx familiar from countless posters, revolution banners, and heroic busts — and the famous headstone in Highgate cemetery — would lose much of its iconic resonance without that frizzy aureole.

Wheen is good at detailing Marx’s defects. He was an incorrigible ‘bourgeois paternalist’ who lived in borderline poverty not for want of funds (a good chunk of which were stolen by Engels for him) but because he insisted on living with the music lessons and other accoutrements of a middle class man. Call him a social realist if you like. Wheen all but does, noting Marx’s anxiety for his daughter’s position in society. But Marx was highly snobbish about his wife’s aristocratic ancestry (‘ridiculously proud about having a bit of posh’) and it bears more scrutiny than the sardonic defensiveness Wheen provides that a man who devoted his life to the cause of Communism had an incurable taste for luxuries. Marx joked about his inability to live under Communism enough times for it to be as revealing as it is funny.

The other limitation of the book is that, although Marx made many great insights about capitalism then, they are no longer true of capitalism now. The largest oversight is that England was the only place where Marx could settle as a sort-of political refugee. No-where else would have him, either because he was Jewish or because he pushed the limits of their tolerance for free speech. It is well understood today that liberalism and capitalism go hand in hand, something which Wheen might have made more of.

More egregious is this:

What Marx did predict was that under capitalism there would be a relative — not an absolute — decline in wages. This is self-evidently true: few if any firms which enjoy a twenty per cent increase in surplus value will instantly hand over the loot to their workforce in the form of a twenty per cent pay rise. So labour lags further and further behind capital, however many microwave ovens the workers can afford.

Apart from the cavalier swatting away of the notion of consumer surplus, which is big and real and a powerful reason why capitalism has survived, this is not a particularly empirical claim. There’s an ongoing argument about whether labour’s share of GDP is declining, and what’s causing that. But labour’s share is declining from its former share of about two-thirds of GDP. Hardly the inevitable, ‘self-evident’, lagging Marx predicted.

The rest of this book is wonderful because it is not concerned with whether Marx was right or not. It’s concerned with him: the carbuncles that prevented him working; the pub crawls; the insane wastes of time on long, poor quality pamphlets rebutting minor statements by inconsequential opponents; the lifelong struggle to live a stable family life; the mystery of whether he screwed the maid; his failure to attend his father’s funeral; the astonishing working routine; the annotations he made on the great classical economists; his passion for Shakespeare and poetry, and his ability to recite it at length on short notice. And so on.

The carbuncles, by the way, are a recurring theme. Marx broke out in boils all too frequently. He used to write to Engels complaining about them, even when they erupted on his penis. There’s a description of Marx slashing the boils on his arse with a razor blade, and delighting in the blood spurting onto the carpet, that made me wince. Writing the last two volumes of Captial was endlessly hampered by Marx’s discomfort from carbuncles. They were so painful he couldn’t sit down, and sometimes couldn’t work at all.

This is a perfect encapsulation of the way this wonderful book enlivens our view of Marx by ‘stripping away the mythology.’ That work is largely done not by defending the specifics of Marx’s predictions, but by showing us the man as he really was, and re-creating his pugnacious, humorous tone.

After all, who knew that carbuncles would take up so much space in a biography of the man who wrote The Communist Manifesto?

Karl Marx, by Francis Wheen (US link)

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.