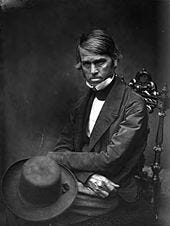

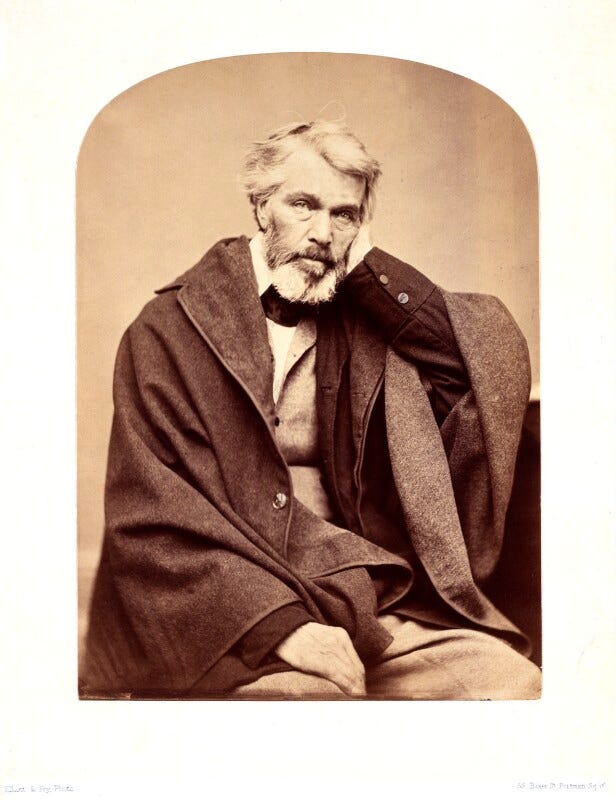

Carlyle and how not to live

Carlyle was impotent. This is the most important fact about him, personal or public. He did not realise his condition until he got married — Froude tells the tragic story of Carlyle thrashing a flower bed to shreds the morning after his wedding. For the rest of his life, that anger never really left him.

The Carlyle marriage is well stereotyped. She was his devoted drudge; he was a genius with the temperament of a child. There are many nuances — her sharp wit, her seeming acceptance of the sort of marriage she got into — but he was, at heart, an intolerable man, made much worse by the fact that he thought he was a genius.

‘Carlyle sees to the heart of society but not into the mind of his partner for life’, Froude said. Jane spent her life being ground down to an early death by Carlyle’s demanding, difficult, deadening behaviour. And he only realised it after she was gone.

That was what prompted him to ask Froude to write the now famous Life of Carlyle. Carlyle’s life work was to make the Victorians see that their materialistic greed was shameful to God and destroying society. As Elliot Gilbert said, ‘Carlyle could not be content merely to enlighten his readers; he wanted to change them.’ Carlyle saw a ‘renunciation of self… as essential to noble action’.

Alas, his own sense of self-abnegation was limited. Even the smallest noise was unbearable to him. And he would rage and wail about a thousand other inconveniences: every day was a litany of the unbearable. Carlyle said on his death bed that his reputation for extraordinary egotism might be why his ideas had not been taken up.

The only thing left was for his redemption to come through a biography. If Carlyle exposed himself and his failings toward Jane — the way he had remorselessly promoted his career at her expense, so badly that he didn’t realise how she suffered until he read her letters when she died — he would be making a self-sacrifice of the sort he had spent his life demanding of others.

As Elliot Gilbert said, Carlyle knew he had ‘no hope of being believed’ about the truth of ‘Christian faith as a living possibility’ without a ‘confirming self-sacrificial act.’ All those books and lectures had done nothing. It was left to his disciple Froude to change minds.

It is doubtful whether anyone has ever read the Life of Carlyle and become convinced of the fact of the incarnation because of the lived reality of self-abnegation. Biography is usually a homage or an exposure. Froude’s was both. His method was dialectic, moving between Carlyle the unappreciated genius and Carlyle the patriarchal brute so often and so easily it’s amazing Carlyle could ever have thought the story of his life could be a vehicle for Christian revelation.

That idea was perhaps Carlyle’s final myopic error, in a long list.

And in fact, realising the true fact of the incarnation was not how audiences reacted. Readers took a more gossipy, fretful approach. Carlyle was devoted to ideas of hero worship and masculinity: when this was delivered as a lecture on Muhammad or a history of the French Revolution it was one thing — to see it as the crux of an intolerable marriage is quite another.

Society was shocked. For a group of people firmly committed to the hypocrisy of nineteenth century marital principles, the horrified reaction is telling. Response to the book became a debate not about the confirmation of an everlasting principle, which is what Carlyle had wanted to prove, but a casuistical discussion on the rights and wrongs of his marriage. It was a scandal.

And inevitably so. Froude was publishing in the era of The Subjection of Women. The world had already been challenged by the sad, romantic story of J.S. Mill and Harriet Taylor. People were nervous about the ways in which stories of bad marriages could undermine the institution. No wonder so many people got so upset. As Trev Broughton says, ‘If Thomas Carlyle, one of the foremost advocates of stoic virtue, could be proved routinely to lose his temper over a missing window wedge, then the future of matrimony was parlous indeed.’

This is where Froude and Carlyle come under pressure. The idea that Carlyle’s life would reaffirm the eternal truth that Christianity is good and laissez-faire liberalism is evil is nonsense. That uncompromising ideological approach is precisely where Carlyle went wrong.

But while Froude says he is defending his master, his approach is different. By using that dialectic method — moving between Carlyle the unappreciated genius and Carlyle the patriarchal brute, never letting one dominate the narrative for long — Froude was being a casuist, hewing not to ultimate principle but demonstrating that this was a unique case, requiring unique judgement.

Carlyle, he assures us, as well as being awful, was a genius. They both knew the marriage was meant to be about lasting achievement and they couldn’t have expected happiness. ‘Those who seek for something more than happiness in this world must not complain if happiness is not their portion.’ If ever a book was written with a ‘practical moral code’ (Froude’s definition of casuistry) it was the Life of Carlyle.

Froude praises Carlyle for four virtues: ‘manliness, thrift, simplicity, self-denial’. All of these were broken, or disregarded, by Carlyle in his marriage. They were practised at the expense of Jane’s health, happiness, and life expectancy. Carlyle thought his society’s pursuit of money would be taken over by ‘God’s judgement’. What God would have made of the Carlyle marriage is not disclosed.

Froude says Carlyle was especially scathing of talented men who ‘no longer had any measure of truth except their own advantage.’ He was talking about ‘statesmen, theologians, philosophers’, but it is eerily appropriate as a description of Carlyle in his marriage. The irony of the sentence, ‘Some who had eyes were afraid to open them; others, and the most, had deliberately extinguished their eyes’, isn’t easy to accommodate, and is astonishing in light of Carlyle’s later remorse about Jane.

Froude must have seen this, even if he didn’t comment on it. His careful splitting of the man from the genius, the husband from the work, is decidedly casuistical.

Carlyle, for example, showed no gratitude to Jane during her many strenuous periods having the house repaired. He was so insufferable he had to leave and live elsewhere while she oversaw this work. Froude says she was ‘struggling… but wishing perhaps that he could show himself a little more appreciative.’ Perhaps, indeed.

Froude tells us Carlyle was misunderstood. He was, in fact, the ‘gratefullest of men, but was too shy to speak of his feelings.’ What was done for him he ‘expected’, and what wasn’t done made him ‘growl’. But Froude reassures us, his letters show the gratitude and feelings that ‘were really in his heart.’

Descend into the particulars of the letters, he seems to say, and the judgement you want to make will not be so easy.

Broughton defines Froude’s casuistic method and conclusion neatly: ‘It was as a writer rather than simply as a husband, that Carlyle's behaviour was problematic: as a Man of Letters he perforce spent his days "alone" at home, exempt from the "wholesome checks" of "active" life: a law unto himself. And it was as a writer that he could and should be forgiven.’

Throughout the book, Froude is at pains to shift the ground, using the casuistical techniques of comparisons, defining through differentiating, introducing new paradigms, to excuse, explain, and soften Carlyle’s behaviour to Jane.

Sometimes Froude’s contorted defences of Carlyle make him sound like Rosalind. ‘Men in the situation of lovers are often selfish. It is only in novels that they are heroic or even considerate.’ Rosalind of course was stoical, accepting. Froude is trying to make Carlyle’s abiding fault an expression of his greatness, describing his behaviour as ‘selfishness of a rare and elevated kind, but selfishness still’.

Jane seemed to have been able to make acidic humour out of her situation. Once she had to go and have a difficult interview with the tax inspector after a sleepless night. She felt, she said, ‘like the ghost of a dead dog’, as she prepared to go. She then comments:

‘Mr C. said “the voice of honour seemed to call on him to go himself.” But either it would not call loud enough or he would not listen to that charmer.’

And this description of them returning home from a journey makes the humour so sharp it’s barely funny anymore.

‘On our return from a visit to Captain Sterling, she [Helen, the maid] would first not open the door; and at last did open it, like a strange ghost very ill got up: blood spurting from her lips, her face whitened with chalk from the kitchen floor, her dark gown ditto, and wearing a smile of idiotic self-complacency. I thought Mr C. was going to kick his foot through her, when she tumbled down at his touch. If it had been his wife he certainly would have killed her on the spot.’

We are reminded of Carlyle thrashing the flower bed to pieces, a young man, suddenly disappointed, doomed to a particular sort of life. And we see that in the intervening years he has become strange, bitter, horrible. Jane is making a dark sort of humour, but it is still ghastly.

We can see, so easily, that impotence was the major theme of Carlyle’s life and work. That obsession with hero worship, with men of action, and masculinity. And that painful, sorrowful impatience with every damned thing that ever happened to him. You don’t need to be a Freudian to see the problem.

Froude wrote in a tragic mode, even comparing himself to a Greek chorus, so he could admonish Carlyle, which was all a way of avoiding the major irony of Carlyle’s life. He was the great prophet who had predicted England was ‘hurrying… on to a catastrophe.’ When in fact the country was fine. Carlyle himself was the one hurrying on to a catastrophe.

Throughout the book, Froude acts like a defence attorney, being revealingly honest about his client, in order to contextualise, redefine, and re-frame the issue. Revealingly honest about everything but the one great fact, of course. Froude didn’t mention the impotence in the Life. That bombshell sat in a drawer until after he died.

If only he had been able to just say it up front: Carlyle was impotent. But, if he had, we might not have got a such a simmering, infuriating, compelling biography of the not-so-great man. All that tension and defensiveness would have been pointless in the face of the one great fact.

The fact that the impotence was a poisonous secret provided the Carlyle’s life with much of its miserable dynamic. That terrible energy is the real revelation, rather than the brute fact itself, which is why Froude’s biography is exceptionally good and wildly entertaining. Whereas reading Carlyle is a tedious punishment, reading Froude is better than watching television with a large bag of crisps.

It wasn’t the effect Carlyle wanted, but his life has become talismanic of what the art of biography can achieve. Carlyle wanted us to learn the eternal truth of Providence — but whatever judgements we can make, they are judgements about that life only.

Biography is about how to live, or in this case, how not to.

Froude’s Life of Carlyle, Clubbe, John ed. (US link). One of the great biographies, this is a one volume version that preserves almost everything Froude wrote, just cutting out the extracts from Carlyle.

‘My Relations with Carlyle’ (1903), Froude’s revelations about impotence were published after his death. (Online edition)

Broughton, Trev “The Froude-Carlyle Embroilment: Married Life as a Literary Problem” Victorian Studies Vol. 38, No. 4 (Summer, 1995), pp. 551-585

Gilbert, Elliot L. “Rescuing Reality: Carlyle, Froude, and Biographical Truth-Telling” Victorian Studies, Vol. 34, No. 3 (Spring, 1991), pp. 295-314

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

I have read little Carlyle but I thought one was supposed to read The French Revolution and I thought he was a genius. I heard Hugh Trevor-Roper say he was a proto-fascist.

This is just brilliant. Absolutely amazing writing.