Cramming vs curiosity—SATs, J.S. Mill and the secret to original thinking.

Should children learn facts or train their minds?

The current row about whether the SAT exams taken by eleven-year-olds are too hard is part of a bigger debate: should we cram children with facts or ignite their curiosity? Not just children. If you are reading this blog, you are interested in your own self-education. The paradox of knowledge versus originality continues into adulthood. It also touches the question of talent—what defines a genius and original thinker?

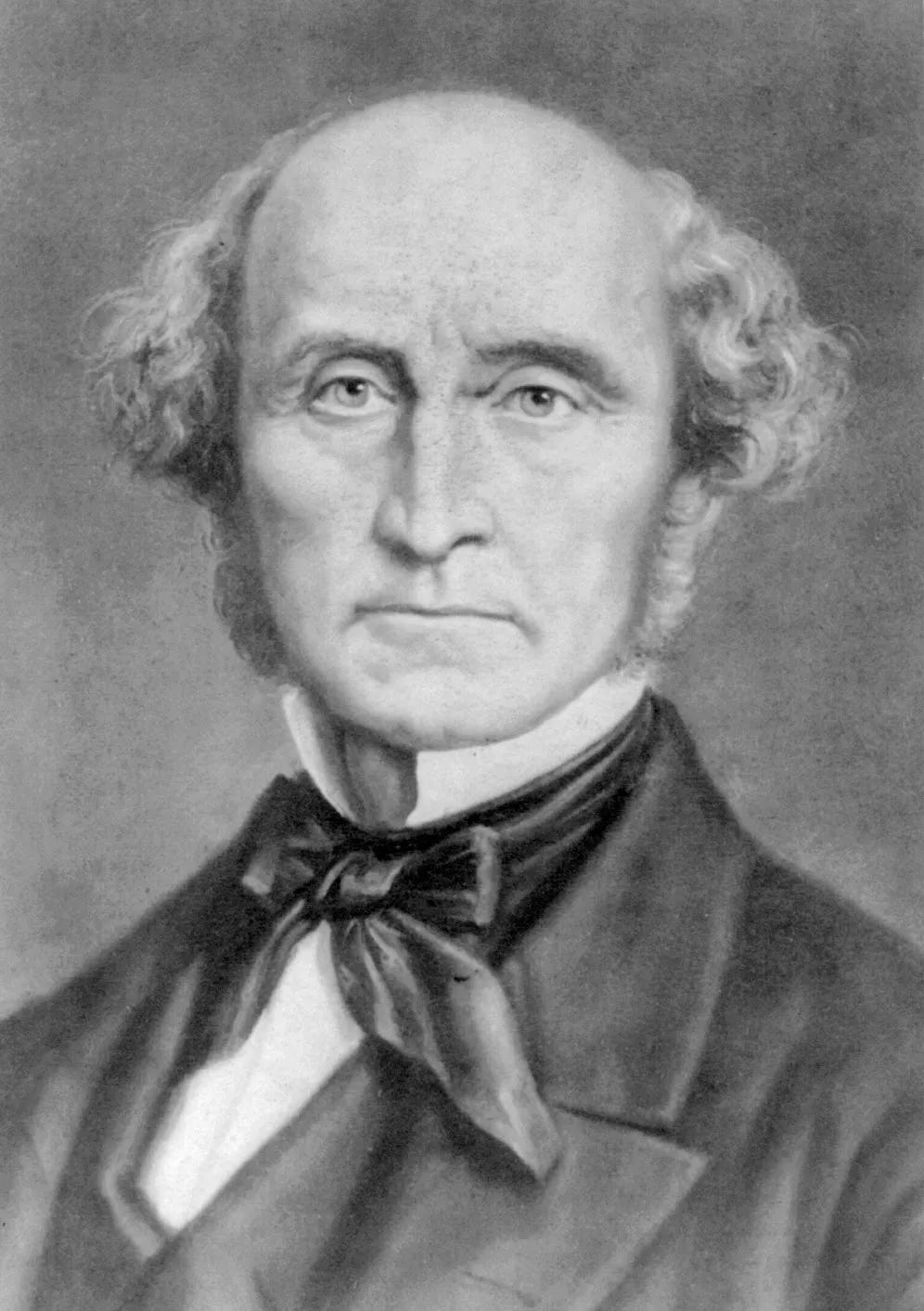

In 1832, John Stuart Mill wrote an impassioned letter to the Monthly Repository. Mill was a lifelong autodidact and original thinker, who believed strongly that education could be improved, and later wrote his Autobiography to record his unusual homeschooling and encourage others to raise their aspirations.

That which has been known a thousand years may be new truth to you or me. There are born into the world every day several hundred thousand human beings, to whom all truth whatever is new truth. What is it to him who was born yesterday, that somebody who was born fifty years ago knew something? The question is, how he is to know it. There is one way; and nobody has ever hit upon more than one—by discovery.

The world is full of school children who have committed something to memory but don’t understand it. Real understanding means thinking or experiencing truth for yourself. We all know the feeling of finally understanding something we had only known as a fact before.

whosoever, to the extent of his opportunity, gets at his convictions by his own faculties, and not by reliance on any other person whatever—that man, in proportion as his conclusions have truth in them, is an original thinker, and is, as much as anybody ever was, a man of genius

You might not find “hidden truths” following this advice—there may be none left, you might miss them—but this is the method that makes someone understand the world in an original way. Genius doesn’t just create, it appreciates.

Without genius, a work of genius may be felt, but it cannot possibly be understood.

Even if we knew everything it was possible to know, there will always be a difference between someone who takes the world on trust and someone who thinks independently.

it will still remain to distinguish the man who knows from the man who takes upon trust—the man who can feel and understand truth, from the man who merely assents to it, the active from the merely passive mind.

For this reason, Mill was against learning by rote. That wasn’t how the Greeks did things. They trained the young to have “an intellect fitted to seek truth for itself.” This was why Mill opposed the cramming system of education. And he said something very relevant to modern debates.

Those who dislike what is taught, mostly—if I may trust my own experience—dislike it not for being cram, but for being other people’s cram, and not theirs. Were they the teachers, they would teach different doctrines, but they would teach them as doctrines, not as subjects for impartial inquiry.

Instead, Mill wanted to teach logic and metaphysics, perhaps ancient languages, to provide “a lesson of logical classification and analysis.” This would raise the level of civilisation. Cram rather than logic is why “ten centuries of England or France cannot produce as many illustrious names as the hundred and fifty years of little Greece.”

He ended with a familiar exhortation.

As the memory is trained by remembering, so is the reasoning power by reasoning; the imaginative by imagining; the analytic by analysing; the inventive by finding out. Let the education of the mind consist in calling out and exercising these faculties; never trouble yourself about giving knowledge—train the mind—keep it supplied with materials, and knowledge will come of itself. Let all cram be ruthlessly discarded.

Perhaps in the age of AI, we will be forced to discard rote learning and start to teach children how to discover the truth of the world for themselves.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment.