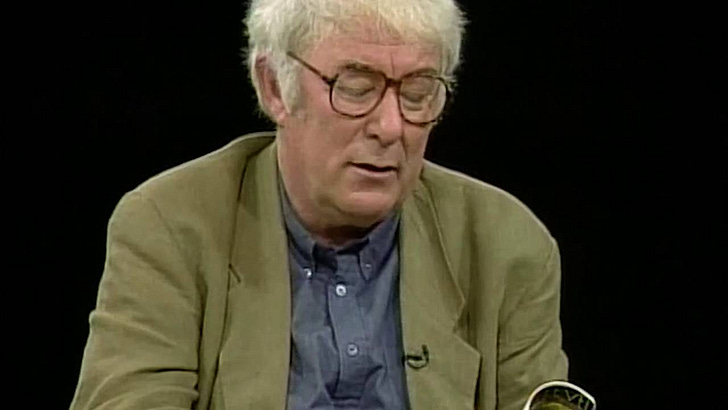

Deep, still, seeable. Seamus Heaney's letters.

The music of what happens and the bundle of incoherence.

The poet of vision

Seamus Heaney found meaning in all things. He characterised poetry as digging into the emotional life of the individual and their society. In “Feeling Into Words”, he talked of “poetry as divination, poetry as revelation of the self to the self, as restoration of the culture to itself.” In a letter, he wrote that the poet “is drawn to redress the balance of circumstances by the weight of the imagination”. His work has mythic qualities, moving from the personal to the cultural, the political. As he said in “Squarings, iii”, Heaney “squinted out from a skylight of the world.” His poetry works to resolve that personal squinted vision with the wider world. The resolution is art.

Through his career, from Death of a Naturalist to Human Chain, birdsong is a symbol of that art. In “Saint Francis and the Birds” Heaney writes the birds “for sheer joy/ played and sang.” Heaney wrote elegies and dark verses, too, but the spirit of his writing was always preservatory, reclamatory, harmonizing, balanced. Part of the power of his work was that it kept what Richard Wilbur once called a “difficult balance” without denying the reality of life in Ireland, and in Northern Ireland especially during the Troubles. His vision was broader than that.

As a poet of vision in troubled political times, therefore, he was trying to have us look beyond the Troubles, to the idea of a solution, to the beauty of the world, to hope. Famously, in 1990, he wrote,

History says, don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up,

And hope and history rhyme.So hope for a great sea-change

On the far side of revenge.

Believe that further shore

Is reachable from here.

Believe in miracles

And cures and healing wells.

Heaney was often at his best when this sort of public poetry commingled with his personal verse. He could start with a memory of his agrarian childhood and end with a broad political ideal, as he did in “Mint”,

My last things will be first things slipping from me.

Yet let all things go free that have survived.Let the smells of mint go heady and defenceless

Like inmates liberated in that yard.

Like the disregarded ones we turned against

Because we’d failed them by our disregard.

Heaney was a poet of regarding things. And regarding is always highly personal.

Deep, still, seeable

Heaney’s immense and earned popularity was the result of this poetic persona: famous Seamus was the gentle, insistent, nostalgic, shy, cheerful, realistic figure who constantly emerged from the poems. From the farm boy who watched kittens drown to the honeymooner running through the Underground to the family man playing Scrabble in his cottage to the old poet reviewing a family photo album, Heaney was loved for his ability to turn himself into public art. Many of his most loved poems feature him or his relatives: he is especially touching when writing about his memories of his mother and aunt. The title poem of his most significant collection Seeing Things is about three memories: a boating trip he took as a child, the facade of a cathedral, and a farming accident that nearly killed his father. The “deep, still, seeable-down-into-water” of “Seeing Things” is immediately reminiscent of the final poem in Death of a Naturalist, “Personal Helicon”, which is about Heaney’s childhood habit of looking down into wells.

Though he is so personal, Heaney always turns his experience into something bigger. The poems try to become, and often do become, what he called “that moment when the bird sings very close/ To the music of what happens.” To hear the music of what happens, Heaney must catch the world, as he said in Seeing Things, when it is “deep, still, seeable.”

The bundle of accident and incoherence

What happened—what actually happened—in Heaney’s own life, therefore remains a large and enticing question. Heaney often quoted Yeats saying, “Even when the poet seems most himself… he is never the bundle of accident and incoherence that sits down to breakfast; he has been reborn as an idea, something intended, complete.” Heaney’s own bundle, and how it was reborn in his work, is now partially revealed in his letters, edited by Christopher Reid.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Common Reader to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.