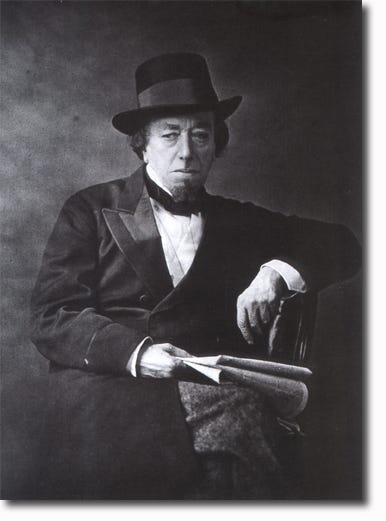

Disraeli, man of imagination

Is Benjamin Disraeli the most misunderstood Prime Minister? Perhaps not. The list of obscure, misinterpreted, or simply maligned Prime Ministers is long. Lloyd George, the man who won the First World War, is primarily remembered as a shagger and a flogger of honours. Bonar Law, his partner in the war time coalition, is called the Unknown Prime Minister.

But among the academy, Disraeli is perhaps most disliked. He was a terrible poseur. He lied, abandoned his principles, and sacrificed other men’s reputations. His early career was a moral catastrophe revised by him into a series of Wildean epigrams. Many of his accomplishments were embellished, won despite himself, or simply opportunistic. Often what were said to be his achievements were nothing of the sort. (Historians talk despairingly about the Disraeli myth.) He is sometimes compared to Boris Johnson.

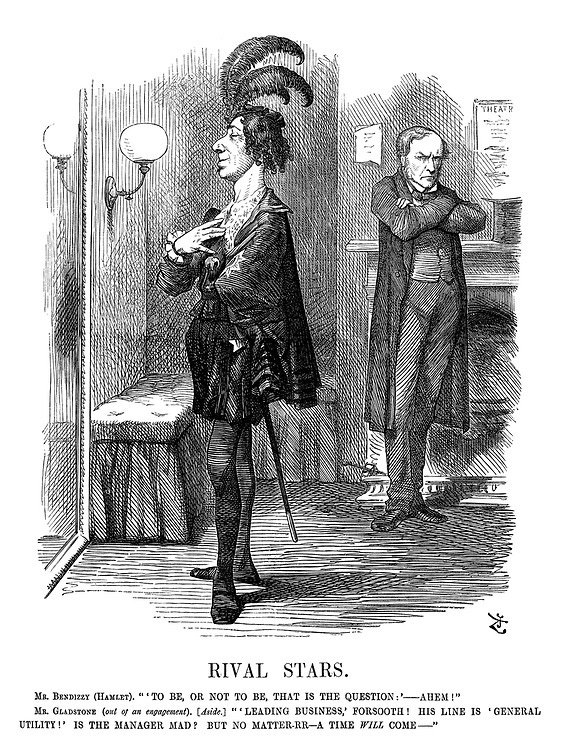

But this is too easy. The idea that Disraeli was a cad, a liar, and a cheat in a world of gentlemen — where he is placed in illuminating opposition to the upright Gladstone — is the stuff of narrative, not history.

It’s true they had such an implacable dislike of each other that Gladstone refused to go to Disraeli’s funeral. And their differences were real. Gladstone felt himself called to Parliament by God; Disraeli suffered from an almost physical lust for fame and power. But there’s more to Disraeli than the charismatic but flawed foil to Gladstone’s towering integrity.

It’s often remarked that he is the only novelist to also have been Prime Minister. In fact, he wasn’t a novelist and a politician, he was a novelistic politician. His great skill was oratory; he was the leading Parliamentarian of the nineteenth century. His command of the House was extraordinary. Always in his place, a master of the rules and procedures, he was for many years the Conservative party’s main, if not, only orator. And he was an exceptional performer.

Everything about him was distinctive. As a young man he had worn bottle green frock coats and blue pantaloons. His hair was curled and he wore his rings on top of his white gloves. He didn’t dress quite so much like a dandy in the House. But he pronounced every syllable of every word. ‘Bus-i-ness’; ‘Par-li-a-ment’. Just before he made especially striking remarks, he would signal to his cheerleaders by drawing a white handkerchief from his left pocket, passing it to his right hand, sniffing it, and then putting it back.

While Gladstone denounced the world, with his long Latin quotations, convoluted sentences, and what Blake called ‘parentheses within parentheses, the lofty moral appeals, ingenious quasi-theological arguments’, Disraeli sat opposite him with his legs crossed, his hat tilted forward over his face, and his eyes half closed. While Gladstone proclaimed, Disraeli lolled. If indignation reached a fever pitch Disraeli roused himself, turned to face the clock on the west wall, and drew his eye glass up to his face very slowly, before subsiding back into his pseudo sleep.

All of this was the garnish. His entire career was built on his sense of performance, from the fierce speeches he made as a young MP that ruined Robert Peel’s career and made him cry on the front bench with his top hat pulled down over his eyes, to the great set piece in the Manchester Free Trade Hall thirty years later, a speech in favour of crown and constitution that lasted for over three hours, during which time Disraeli sustained himself with two bottles of white brandy. He represented the conservative spirit of the age, and if he was a mediocre Prime Minister he was an exceptional politician.

It wasn’t clear when Disraeli was young that he would be successful. His early life was, in fact, outrageous. John Morely, Gladstone’s biographer, reviewing the first volume of Moneypenny’s Life of Disraeli for The Times, drew a contrast with the ‘literary extravagences’ of young Disraeli and the ‘cool, shrewd, patient, far sighted, practical… master of the fatiguing art of managing men.’ An anonymous reviewer of Moneypenny’s first volume in The American Historical Review was astonished at just how little signs of his later success Disraeli showed in his early life:

if the contents of these four hundred pages were all that was known of Disraeli, there would be little to suggest that [he]... could be of any great service to a political party that was really attached to political principles and dependent for its strength… on the votes of a middle class electorate.

What was it that the young Disraeli had been doing that so outraged and bamboozled people reading the story of his life in 1911? Where do we begin…

Between 1824-1825 he speculated wildly and indebted himself for decades. He double crossed (and was double crossed by) Lockhart and Murray about a newspaper he set up with them. And then he published a novel that revealed in disobliging terms the details of those messy, ridiculous dealings, thus seriously impairing his chances of preferment among the people who would be important to his political and literary career. It was a soap opera affair, full of gossip, betrayal, and intrigue, and it ended badly.

Jane Ridley, a sympathetic biographer who covers Disraeli’s early life, says of this period:

Disraeli’s adventures of 1824-25 strikingly prefigure his later career. The allure of the press; the excitement of the ‘great business’, of dramatic cloak-and-dagger schemes and behind the scenes politico-financial coups; the settling of grudges in print; the cycle of frenetic activity followed by nervous prostration – all these were to recur time and again throughout his mercurial career.

1825 was a turning point in Disraeli’s life. He failed, badly, and ended up depressed. He had speculated on shares and the crash left him with debts he wouldn’t clear until his fifties. For most of his career, if he had failed to get elected he would have been in debtors’ prison. When he first joined Parliament in 1837 he had to be sneaked in dressed as a cook so that his creditors couldn’t arrest him before he was sworn in as an MP. At Hughenden, his country home, he once hid from debt collectors in the well.

So he was left with lifelong debts and no prospects. However, the times had changed. The crash of 1825 was a major turning point, politically and economically. It also opened up the book trade. Alexander J. Dick explains that one result of the crash was the emergence of mass market books.

Taking advantage of the misfortunes of their former competitors, smaller publishers like Thomas Tegg began to buy up their stock at a fraction of the original costs and reissue them in cheap editions (Sutherland 157). Other publishing entrepreneurs such as Charles Knight and Henry Coburn soon followed Tegg’s lead and the market was soon awash in affordable editions. The equation, assumed by Murray and others, between literary reputation and expensive, limited editions was superseded in the market by the idea that financial reward came from mass sales. Indeed, establishment publishers responded in kind. Murray began issuing his Family Library and Longman the Cabinet Encyclopedia (Hilton, Mad, Bad 20). The vogue for these series reached its apex in the early 1830s with Scott’s Magnum Opus and Bentley’s Standard Novels. The demand for cheaper fiction after 1826 also inspired one of the most crucial literary trends of the nineteenth century: serialization.

From here on out, Victorian novels would straddle ‘the divide between academic and popular markets that the 1825 crisis had opened up.’ Disraeli’s success, as a novelist and a politician, was his ability to appeal to an increasingly popular market. He did this in part by creating his own myth. Just as Dickens would dominate the domestic Victorian imagination with his novels, so Disraeli dominated the political imagination with his novels, oratory, and sheer personality.

We tend to underestimate the force of political personality today. In the nineteenth century they were used to the moral power of speakers like Palmerston and Gladstone. During the 1879 campaign, Gladstone reinvented himself as leader. He burst out of supposed retirement and ignited the country to vote for a great Liberal victory. As the historian David Brooks says,

Contemporaries acknowledged his powerful public presence: 'the dark large eyes, beneath heavy wrinkled brows' which did still 'flame out as they were wont to do in earlier days', and 'the rich harmony of that melodious voice which had a charm almost of physical persuasion.

Disraeli’s use of personality was equally powerful. In 1875 the government had made a purchase of shares in the Suez canal, largely to secure trading routes. This was a mundane policy, pursued in the usual bureaucratic manner. But it required financing, and Disraeli secured the money from Rothschild, while Parliament wasn’t sitting.

This was presented as a coup. Disraeli was supposed to have faced down the cabinet, who didn’t want to make the purchase, and to have won through with his initiative and daring personality. He told Lady Bradford the French couldn’t be allowed to take control of the canal because they might shut it up. As Geoffrey Hicks says,

The image was fanciful, but the fear was palpable: here was a concern for economic virility that would increasingly affect British nerves in the late nineteenth century…

Disraeli was being novelistic, dramatising himself and the issue — and it worked. The Daily Telegraph switched to supporting Disraeli. The issue played to serious concerns among the voters and helped to shift the political balance. We might not admire his integrity, but we have to concede his panache, his ability to contrive.

Sarah Bradford (who makes the mistake of attributing the Suez share purchase to Disraeli’s solo, dramatic impulse) notes that ‘Public opinion as a whole now saw the Suez Canal share purchase in the light in which Disraeli presented it.’ Lord Derby (the cautious one) himself was of the view that the purchase would be popular, and although he began with seemingly reasonable objections they were dropped quickly. The story and Disraeli’s role have been exaggerated, but it is hardly false.

There’s always some reality behind the myth with Disraeli. He was reprehensible in many ways — he destroyed Robert Peel over the Corn Laws, famously saying Peel had caught the Whigs bathing and then stolen their clothes, and then thirty years later he did exactly the same thing when he stole Gladstone’s Reform Bill and passed it off as his own. But he was politically ingenious, a man of great imagination and oratorical power, and his myth became the foundation for the Primrose Society, the popular movement in the twentieth century Conservative Party, perhaps the largest mass political movement ever known in Britain.

He started off by splitting Peel’s party, but in the end without him the Conservative party might easily have fallen apart. He charmed the Queen, invoked the patriotic spirit of the nation, passed progressive legislation (like slum reforms), and stood as a powerful counterpoint to the Liberal party, something no one else could have done as well. He also formed an alliance with Bismarck, which, if he hadn’t then lost the 1880 election, would have been a better position for the country to go forward with in the decades that were leading, ultimately, to war with Germany.

We don’t have to respect him any more than we do, but we could appreciate his contribution, and his abilities, a little more. He was the great Prime Minister of imagination.

Disraeli is a late bloomer. Read more about late bloomers here: The case for opsimaths. Maybe late bloomers aren't so late

For my other blogs about Prime Ministers, read Who was Asquith?

There’s a lot of excellent material about Disraeli. Here are some recommendations.

Robert Blake’s Disraeli (US link) is one of the best biographies ever written.

Jane Ridley’s book The Young Disraeli (US link) is an excellent, entertaining account of his early life.

For more on the Suez canal purchase, read Geoffrey Hicks, ‘Disraeli, Derby and the Suez Canal, 1875: Some Myths Reassessed’, History , April 2012, Vol. 97, No. 2, 182-203

The ONDB entry on Disraeli by Jonathan Parry is thorough and informative.

There are some good podcasts

Other references

David Brooks, ‘Gladstone and Midlothian: The Background to the First Campaign’, The Scottish Historical Review, Vol. 64, No. 177, Part 1 (Apr., 1985), pp. 57-58.

Dick, Alexander J. “On the Financial Crisis, 1825-26.” BRANCH: Britain, Representation and Nineteenth-Century History. Ed. Dino Franco Felluga. Extension of Romanticism and Victorianism on the Net. Web. [accessed 28/01/2021].

‘The Life of Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield by William Flavelle Monypenny: Review’, The American Historical Review, Vol. 16, No. 3 (Apr., 1911), pp. 627-628

Lord Morely, ‘Review of Disraeli’, The Times, 27 October, 1910. p. 397

W. L. Courtney, ‘Disraeli. Author and Statesman. Early Career. Mr. Moneypenny’s first volume.’ Telegraph, Thursday, Oct. 27, 1910, p. 13.

A. G. Porritt, ‘The Life of Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield by William Flavelle Monypenny’, The American Political Science Review, May, 1911, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 291-292

‘The Young Disraeli’, TheTimes, Thursday, Oct. 27, 1910, p.9.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.