James Marriott in the Times has written that “there is a hard, bright intensity to the flame of youthful genius that doesn’t burn much past 30.” James is absolutely right in his broader thesis that the flourishing of young talent is essential to a lively culture. “Youthful genius has a special, anarchic power that our society is not currently good at harnessing.” Agreed!

But in his enthusiasm for his thesis, James made some quite contestable statements about how talent changes as we age. The genius of age can also burn brightly.

Psychologists tell us that “fluid intelligence” — the power of speed, abstraction and logic — peaks at 20. “Fluid intelligence” will strike most Dylan fans as an apt description of the flashing currents, spiralling eddies and surreal gushes of association that characterise his best songs.

“Fluid intelligence” is also the hydraulic force that drives the great breakthroughs in physics and mathematics. Most of the pre-eminent geniuses of 20th-century physics started young: Werner Heisenberg, Niels Bohr and Paul Dirac were 23, 28 and 26 respectively when they made their world-historical achievements in the discipline. “A person who has not made his great contribution to science before the age of 30 will never do so,” said Einstein in a phrase that haunts tardy PhD students. He published his own special theory of relativity at 26. The Fields Medal for mathematics is awarded only to those who are 40 or younger.

I have two chapters about this in Second Act. The quotes below are from those chapters. (They are not the whole argument, for that you need the book.)

One point James missed is that the average age of achievement in scientific fields has shifted over time, suggesting that the age of accomplishment is as much to do with factors like the burden of knowledge as it is with inherent ability at a certain age.

Before 1905, 69 per cent of chemists, 63 per cent of medical scientists and 60 per cent of physicists did their Nobel prize-winning work before age forty. Something like 20 per cent of their prize-winning work was done before age thirty. By the end of the twentieth century, almost no prize-winning work was done before the age of thirty. And in physics, great achievements before the age of forty happen about one-third as often as they did a century earlier. The average age for doing prize-winning work increased by seven years for medicine laureates, ten years in chemistry, and thirteen years in physics. Most strikingly, at the start of the twentieth century, 66 per cent of prize-winning work in chemistry was done by age forty. By the end of the century, that number was close to zero.

As for G.H. Hardy, who said maths was a young man’s game,

Ironically, Hardy admitted to being a late bloomer himself. Of his collaborations with the mathematicians John Edensor Littlewood and Srinivasa Ramanujan he wrote, ‘It is to them that I owe an unusually late maturity: I was at my best a little past forty.’ Another irony of this book is that Hardy uses Euclid’s theorem of an infinity of prime numbers as a way of demonstrating how maths works. This theorem gave rise to the twin prime conjecture, a problem that has remained unsolved for over a hundred years. The most recent major advance towards solving this problem was made by Yitang Zhang, aged fifty-five.

And here is why the Fields Medal is awarded to those under the age of 40.

The 1950 committee discussed criteria for nominating people. The chair, Harald Bohr, wanted a young mathematician called Laurent Schwartz to get the medal. The other leading nominee was André Weil. Bohr suggested a cut off of age forty-two, seemingly because André Weil had turned forty-three the previous year. Bohr argued, for reasons of international politics and ‘the encouragement of further achievement’, that age was an important factor in choosing the winner. But really he was concerned to have his candidate succeed and used the arguments necessary to ensure the outcome. It was committee politicking that ensured the Fields Medal was a prize for younger mathematicians. In 1966, forty was chosen as a convenient round number for the age limit.

We actually don’t know whether maths ability declines as much as we believe: the fact that we believe this so much has become self-reinforcing.

In 1978, sociologist Nancy Stern published a paper about mathematics, age and productivity. She looked at the number of papers mathematicians wrote at different ages, and she concluded that: ‘There is no apparent overall relationship between age and mathematical productivity.’ Table 10.1, which summarizes her results, shows you can be productive as a mathematician at any age.

A few years before Stern’s paper, Stephen Cole investigated age and scientific performance. He found that there was a ‘slight increase in productivity through the thirties’ and then a ‘slight decrease in productivity over the age of 50’. Both, he said, were ‘explained by the operation of the scientific reward system’. The ones who keep publishing form a ‘residue’ of the best members of their cohort; the others were disincentivized from carrying on.

Imagine a world without tenure, where the Fields Medal sets the cut-off age on factors other than internal politics, and you might start to see more breakthrough from older mathematicians like Yitang Zhang. It is very notable that Zhang had an entirely untypical career and was not actually interested in the usual status markers of other academics. (I tell his story in more detail in Second Act.)

Second Act also deals with simplistic interpretations of fluid intelligence. The real picture of how our intelligence changes over time is more complicated!

…processing speed (matching numbers and symbols) peaks much earlier than working memory (unfamiliar shapes and reciting lists of numbers). These are both aspects of fluid intelligence, but they peak at different times. The idea that fluid intelligence is one thing and declines early isn’t quite right. There are many aspects to intelligence and they peak at different ages throughout our lives. The authors of the study say: ‘Not only is there no age at which humans are performing at peak at all cognitive tasks, there may not be an age at which humans are at peak on most cognitive tasks.’

The average is real, but there’s a lot of variation around the average. Some people, in fact, score better on intelligence tests when they are old.

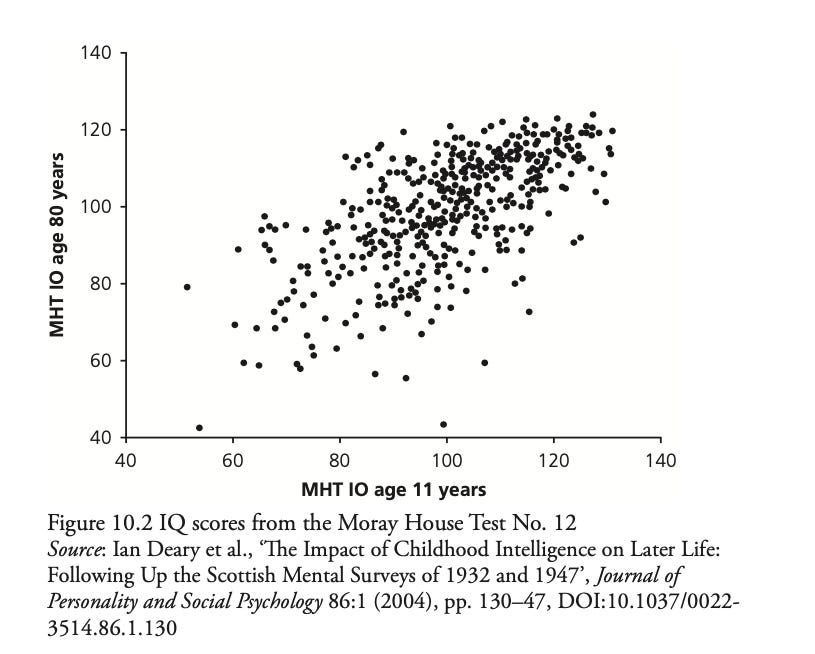

On 1 June 1932, almost every schoolchild born in 1921 and attending school in Scotland took the same intelligence test. This was the Moray House Test No. 12, similar to a school-entrance exam that measures IQ. Split roughly equally between boys and girls, 87,408 children took the test. The same thing was done in 1947, with another 70,805 children born in 1936. Ian Deary, and a group of intelligence researchers, contacted hundreds of these people many years later and gave them the same test they had taken at about age eleven. This allowed Deary and his colleagues to see what happens to intelligence over seventy years.

This chart shows the results.

Look at the horizontal axis. This is the IQ as measured at age eleven (standardized to be a mean of 100 at that age). From 100, which is the average IQ, look up the graph and you will see that people who scored an IQ of 100 at age eleven were scoring between 40 and 120 when they were aged eighty. Although there is a general trend for people’s IQ to be approximately the same at the age of eighty as it was at the age of eleven, this is by no means a sure thing. The average conceals a lot of variation.

What’s really interesting is how to explain the variation between people’s scores age eleven and eighty. Is this variation caused by genetics or environment? Deary says: ‘About half the differences in people’s intelligence test scores in older age are not accounted for by childhood intelligence.’ That means that half of the changes in the scores (when people’s scores improve or get worse over time) can be explained by their childhood intelligence. The other half has to be explained by other factors.

James also repeats the old canard that great lyric poetry is written by the young. Yes, great Romantic lyric poetry often was (per his examples), but they mostly died young. Shakespeare’s sonnets and Donne’s religious poetry counter-balance Keats and Coleridge quite forcefully! Robert Frost and Wallace Stevens wrote some of their most canonical work after they turned fifty, including ‘Stopping by Woods’. There is also Tennyson, Yeats, Larkin, Hughes…

Beyond the lyric, it becomes simply inarguable. Shakespeare was thirty-five in 1599, after which he wrote Hamlet, Twelfth Night, the other great tragedies and the Romances. Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales in his fifties. Milton wrote Paradise Lost in retirement. Dante! Pope! Virgil! Yes there are plenty of young poets, but the idea of the Young Poet is a Romantic idea.

James is right that we need to encourage young talent, but talent is not as exclusively youthful as he says.

If you want to know more, read Second Act!

Thank God for that. I've published two books I'm pleased with, and have a third on the way, but at 69 I still don't feel I've written my masterpiece. And my first book, a collection of stories, was published when I was well over 50.

"A million million spermatozoa,

All of them alive:

Out of their cataclysm but one poor Noah

Dare hope to survive.

And among that billion minus one

Might have chanced to be

Shakespeare, another Newton, a new

Donne —

But the One was Me.

Shame to have ousted your betters thus,

Taking ark while the others remained

outside!

Better for all of us, froward Homunculus,

If you’d quietly died!"

— Aldous Huxley, Leda: Fifth Philosopher's Song, 1920

------

"I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein's brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops". Stephen Jay Gould, The Panda's Thumb