Discovering Hannah Crafts

In 2012, the literary scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. saw a manuscript for sale in an auction catalogue, from the collection of Dorothy Porter Wesley, which immediately pricked his interest. Wesley was a great librarian and bibliophile who had amassed one of the great collections of African-American literature. When she retired in 1973, Wesley had collected over 180,000 items. Her collection is one of the major wellsprings of the scholarship of African-American history that has flourished since the 1960s.

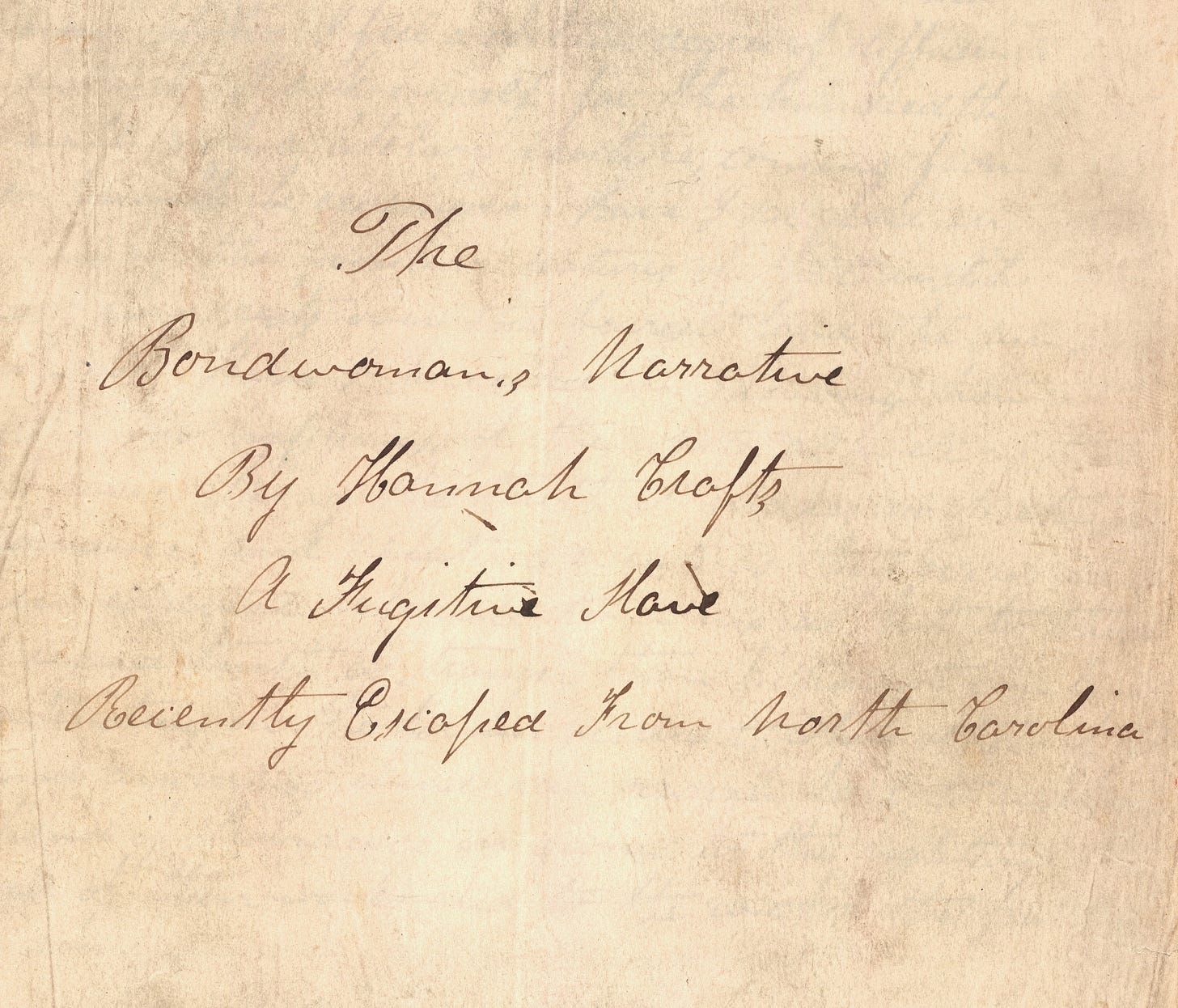

No wonder, then, that Gates was intrigued. Especially because some of the other notes in the auction catalogue suggested that the manuscript in question, written by Hannah Crafts, might be the first novel written by an enslaved woman, possibly the first American novel written by a black woman. No wonder, too, that Gates was astonished to find, after the auction, that he had been the only bidder.

In 2002, Gates edited and published The Bondwoman’s Narrative, a page-turning narrative about the life of a slave woman, the horrors she sees and suffers, and her escape to freedom. It is a brisk, bitter, unflinching account of the evils of slaveholding and the struggle for liberation, as well as a satire of contemporary life. Though I have had my stomach turned by the accounts of physical violence towards slaves in Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs, I was grimly astonished by the early hanging scene, which must rank as some of strongest testimony of evil written in the nineteenth century.

Now a new biography has been released, The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts by Gregg Hecimovich.

Crafts’ Dickensian craft

Crafts is a highly literary novelist. From the opening line, Dickens is unavoidable. Bleak House is everywhere. Many passages are clearly imitated, parodied, copied, or pastiched. Characters are adopted and adapted. The dynamics of their relationships are transposed from London aristocracy to Southern slaveholders. Even Mrs. Perkins and Mrs. Piper, the minor characters Dickens uses to control the flow of time at the inquest into Nemo’s death, appears in Crafts’ novel.

During a scene in The Bondwoman’s Narrative, when Hannah’s owners are discussing how he might secure a political appointment through his wife’s good looks, Mr. Wheeler says that Mrs. Perkins had achieved something similar for her husband.

“Mrs Perkins” retorted the lady scornfully “you don’t call her beautiful, I hope.”

“Rather good-looking, that is all, and nothing comparable with you. I was thinking, however, that as her good looks accomplished much, perhaps your beauty might do more.”

A gleam of intelligence flitted over her countenance, mingled I thought with an expression of slight displeasure, and she inquired in a voice raised somewhat above the common key. “Is it possible that you wish me to do as Mrs Perkins did? Is it possible that you desire me to hang around some haughty official till I weary him with continual coming, that you ask me to weep before him, and kneel at his feet with importunities that will not be answered in the negative?—is it possible Mr Wheeler, I say—?”

So closely does Crafts stick to Dickens here that the woman Mrs. Wheeler is competing with for this new job is Mrs. Piper, who, in Bleak House, is Mrs. Perkins’ friend. At first appearance, Mrs. Perkins and Mrs. Piper have not been on speaking terms. A similar contention exists between Mrs. Wheeler and Mrs. Piper in Bondwoman.

In Bleak House, Mrs. Perkins and Mrs. Piper are used to link the inquest to the life in the court around the house where Nemo died. When Mrs. Piper gives evidence at the inquiry, her speech is reported indirectly. The narrator becomes her ventriloquist, which allows Dickens to continue his satirical reportage, brings pace to a large piece of narrative, and draws attention to important details indirectly. All this lets Mrs. Piper take her place in the panoply of Dickens’s vast novel without breaking the narrative flow. She also introduces several other minor characters. Her speech contains short sketches of Nemo, Jo, her husband, and her child. In this way, she not only adds pieces to Dickens’ mosaic of London, but inadvertently introduces a plot twist. She unknowingly reveals a link between Jo and Nemo that drives the mystery forward.

Similarly, in The Bondwoman’s Narrative, Mrs. Perkins and Mrs. Piper are reported indirectly, through other characters’ speech. They broaden the novel’s scope, satirising life in Washington D.C., but also satirising the Wheelers by juxtaposing them with Mrs. Perkins and Mrs. Piper. They are so mean spirited about them, but quite prepared to do what they did—to use Mrs. Wheeler’s looks to win Mr. Wheeler a job. Mrs. Wheeler’s unkind comments about Mrs. Perkins—you don’t call her beautiful I hope—make a small, but powerful, prolepsis for the scene that comes a few pages later when Mrs. Wheeler’s face powder turns her skin black. She is then bitter about the degrading way Mrs. Piper has spoken to her, barely aware of her own black servant who is in the room with her. Crafts doesn’t just use Mrs. Perkins and Piper to expose hypocrisy, lash vanity, and denounce racism: she sets up Mrs. Wheeler’s pride before her fall. All with the Dickensian use of a character so minor you might almost forget she was there.

Crafts knew that, in Bleak House, Mrs. Perkins and Mrs. Piper gossip about a married mother who performs at local “Harmonic Meetings”. She is billed as a siren but her baby is smuggled in to be fed. The two women are content to dismiss this as hypocrisy: “a private station is better than public applause.” They thank heaven for their own respectability. This scene is mildly comic, a gentle satire on common morality. Crafts transfigures it into a scathing attack on the way that, in her world, private hypocrisy solicits public applause. Like the Dickensian characters, Mrs. Wheeler is scathing of others’ faults—but then hatefully appalled when those others are scathing of her same failings.

A novel with everything

This is only one example of Crafts’ abilities. Again and again, she plays off Bleak House to tell her own story of a corrupt society. The Bondwoman’s Narrative is an example of the fact that the only truly adequate response to a great novel is to rewrite it. Nor is Crafts merely Dickensian. As the scholar of African American literature Hollis Robbins wrote (in In Search of Hannah Crafts (2004)),

If a roomful of witty and well-read literary scholars wanted to concoct a readable text composed of the highlights of nineteenth-century literature, they might come up with something like The Bondwoman’s Narrative. It is an amalgamation of the era’s greatest hits — the mysterious old house; the portrait gallery; the questionable parentage subplot; the escape; the imprisonment; the carriage accident; the story of the jealous wife and the philandering husband; the cruel, lascivious slave trader; the heartbreaking sale of family members; the kindly old couple whose cottage provides refuge; the reunion of old friends after long years; the ghosts; the documents; the disguises; the injustices; the pranks; the satirical-political asides; the revenge; the achievement of freedom and some financial security; the final scene of domestic tranquility. Each chapter has an ironic epigraph, usually biblical, and is sprinkled with faux-erudite allusions to literary greats. In short, the novel has everything.

Finding the real Hannah Crafts

Crafts has been the subject of much scholarly inquiry. That we have her work at all is the result of much hard work. Without Dorothy Porter Wesley’s lifetime of dedicated collecting, who knows where Crafts’ book would be now. So dedicated was Wesley that for her first major assignment, cataloguing Howard University’s African-American history collection, she literally walked the stacks to find relevant books. Edward L. Lach Jr., writing in American National Biography, says that Wesley “was notorious for raiding attics as well as the occasional trash can for material of worth.” Finding the Dewey Decimal System inadequate for cataloguing African-American work, Wesley reformed it. So protective of her collection was she that, during student riots in the 1960s, she defended it herself, physically.

Once Henry Louis Gates Jr. had the manuscript, he spent many weeks trying to establish Crafts’ identity before The Bondwoman’s Narrative was published, compellingly recounted in the introduction. Robbins herself tried to uncover Crafts’ identity, having been the scholar who discovered that Crafts probably got her knowledge of Dickens from Frederick Douglass’s newspaper.

This long trail of work (which includes other scholars) has come to a head in the scholarly and readable biography The Life and Times of Hannah Crafts by Gregg Hecimovich.

Hecimovich reports that many scholars, himself included, initially found it unbelievable that this novel could have been written by a fugitive slave. Why should this be surprising? The human capacity for education is vast. We forget how malleable and enquiring our minds can be. Young Dickens was hardly well-educated by modern standards, yet he became the great literary voice of his day. Plenty of slaves were taught by kindly older women. Crafts was clearly an attentive and perceptive reader.

And, of course, she is who she seems to be. Her novel is deeply autobiographical, as Hecimovich’s careful book shows. His attentive scholarship is a great tribute to her abilities. Among its many wonders, The Bondwoman’s Narrative should remind us not to be astonished when people like Hannah Crafts write great novels, but to wonder at how strong the instinct to read and write can be, especially in children. Even among the great evil of the antebellum South, those instincts could not be destroyed.

I recommend Hecimovich to you all, but not, of course, as much as I recommend The Bondwoman’s Narrative.