Happiness research needs a new philosophy

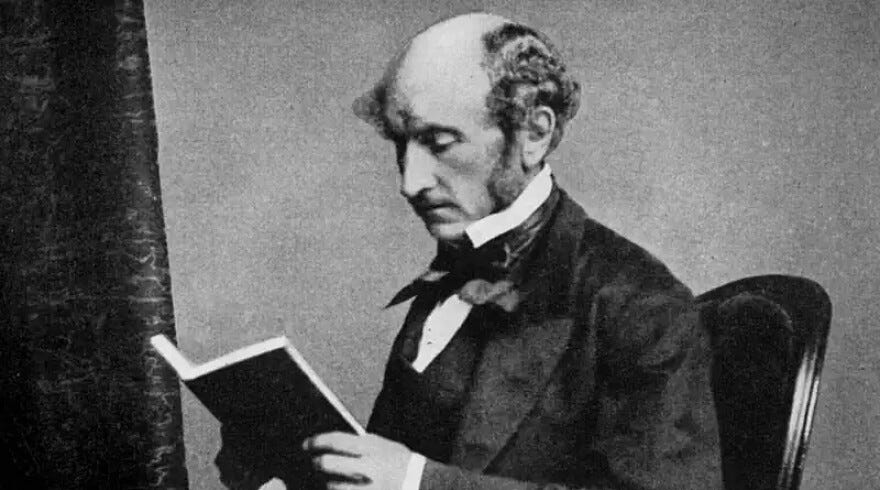

Was John Stuart Mill happy?

Happiness research is wrong

New research shows that older people become less happy after a certain age. You might think this isn’t news. But it is a much debated point in happiness studies. The idea of the U-bend theory of happiness is that we see, on average, a decline in happiness in middle-age, followed by a recovery into old age. Some people even think apes display this natural middle-aged dip followed by the sunlit uplands of retirement.

Part of the disagreement comes from the way researchers select data. When researchers look at a one-off snapshot, happiness seemed robust into old age. When they track the same people over time, they see happiness decline into old age. Also,—and this you can file under “Who needs science to tell them that”,—researchers have found that older people are happy when socialising, working, volunteering, and exercising and unhappy when their spouse dies or they become immobile

I’m sceptical of the U-bend theory of happiness (and most other happiness research) and will have more to say about that in my book. As the authors of a 2018 paper which showed poor replication of many happiness finding said, happiness researchers, “rely on the assumption that all individuals report their happiness in the same way.” That’s quite an assumption.

That 2018 paper also shows that once you remove any assumptions about the way happiness is distributed, you don’t find many patterns. Ideas like “married people are happier” or “there’s a U-bend of happiness over a lifetime” just don’t seem to exist in the data. If you assume happiness has normal distribution, like a bell curve, you find theU-bend. If you don’t assume that, you see that there is no possible ranking of age groups by average happiness. When you look at all age brackets on a four-point happiness scale, you find people of all ages at all points on the scale.

What are we even asking?

What’s going wrong, other than the imposing of assumptions about distribution, is that happiness researchers lack a proper philosophy of happiness, as shown by their narrow questions. As I said in my rant about children’s movies, “Life is not a quest where you meet a candyfloss elephant and rescue the day with his rainbow rocket trolley.” Happiness is more complicated than having fun.

Think about some of the ways philosophers have talked about happiness. Is happiness about feeling pleasure not pain, is it about fulfilling our desires, even if they don’t give us immediate pleasure—or perhaps no guarantee of pleasure—or is it about living according to a set of standards to achieve excellence? Say there is something you want to achieve with your life and you work hard to try and achieve it: perhaps you will always be dissatisfied with what you accomplish. Derek Parfit gives the example of George Eliot, saying, “The struggle to achieve may not be the kind of struggle which is its own reward.”

How well can any of these ideas be captured in the question, “Taking all things together, how satisfied are you with your life these days?” Other researchers ask similar questions like “On the whole, are you very satisfied, fairly satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied with the life you lead?”

We are not all George Eliot, but this seems rather thin. Is it even possible to “take all things together”? Can a happy family life compensate for not achieving what you want to professionally, or vice versa? That seems to fly against common sense. Perhaps for many people, success in one area can be weighed against failure in another, but it’s a blunt way to think about happiness.

Try this as an example. Was John Stuart Mill happy? Mill was a prominent philosopher of happiness, who codified and expanded Benthamite Utilitarianism, the belief that we should aim to maximise pleasure and minimise pain. Mill is often called a hedonist for this philosophy of maximising pleasure. Looking at his own life—stern father, unloving mother, intense education, deep depression, career chosen for him by his father, a short marriage ending in early death after a twenty year platonic affair—he might seem unhappy on his own terms. It hardly looks like a life where pleasure was maximised.

I don’t believe Mill thought like this. John Gray points to this passage, from On Liberty, and others like it, to show that “personal autonomy” is central to Mill’s thinking:

A person whose desires and impulses are his own—are the expression of his own nature, as it has been developed and modified by his own culture—is said to have a character. One whose desires and impulses are not his own, has no character, no more than a steam-engine has a character.

Samuel Clark says of Mill’s Autobiography:

It’s an example, because that life shows what development is possible with the right educational conditions; but it’s also a warning, because it also shows the ways in which development can be thwarted, and a human life made worse than it might have been.

Mill’s whole project was that people should be able to fulfil themselves, use their talents and faculties,—become the best version of themselves, we might say now.

Mill’s Autobiography was modelled on the Romantic genre of Bildungsroman, a story that shows the moral development of an individual from childhood to maturity. This was a common theme of the nineteenth century novel, showing the way a character grows over time. Mill thought that the ideas you believe shape the course of your life. What you think is who you are.

Mill’s view of happiness is a life that makes the most of someone’s potential by providing them with autonomy—we all go through a Bildungsroman.

As we will see, this is a messy idea, not easily amenable to a survey, but it gives us a better grasp of what happiness really means.

The heart asks pleasure first.

The Benthamite view (maximise pleasure, minimise pain) is sometimes contrasted to the Aristotelian view, which is concerned with the development of character and excellence. For Bentham, to be happy we must do what we enjoy; for Aristotle, we must do what we ought to do.

Mill was neither an entirely consistent Benthamite nor Aristotelian. He wanted people to be free and capable of perfecting themselves, but he knew from his experience of depression that being entirely concerned with excellence and doing good is not sufficient: you must enjoy life too.

Martha Nussbaum explains this blended philosophy,—which has often gotten Mill accused of being inconsistent:

[Aristotle] places too much weight on ‘correct’ activity—not enough on the receptive and childlike parts of the personality. One might act correctly and yet feel like “a stock or a stone.”

This is exactly what happened to Mill, he was only concerned with acting correctly and had to learn to feel, to take pleasure in life for his own sake.

… it was the very childlike character of Bentham, the man who loved the pleasures of small creatures, who allowed the mice in his study to sit on his lap, that made him able to see something Aristotle did not see: the need that we all have to be held and comforted, the need to escape a terrible loneliness and deadness.

Rather than come to a single unified theory of happiness, one that picks a system, or fits neatly into a research question, Mill set out principles that sit together, not perhaps in unbreachable logical order, but true to life. As Nussbaum says.

Mill stands out–an adult among the children, an empiricist with experience, a man who painfully attained the kind of self-knowledge that his great teacher lacked, and who turned that self-knowledge into philosophy.

Until happiness research can grapple with Mill’s emphasis on self-knowledge, balancing different conceptions of the good, and flourishing through autonomy, its results are going to continue to be at the level of “old people with mobility problems are less happy than those who do regular exercise.”

Become a Subscriber

Paid subscribers get extra essays, like this one about the nineteenth century idea of literary talent.

They also join the Common Reader Book Club. Last time we discussed David Copperfield and subscribers got my essay and video about the context of the novel, its relation to Dickens’s life, his stinking antifeminism, and how Copperfield encodes Carlyle’s idea of heroes, something I think critics have overlooked.

The next book club is on 9th July 19.00 UK time. We are reading Mrs Gaskell’s biography of Charlotte Bronte. Some people can’t make it so I will organise a mid-week session also. Email me or leave a comment if you have a preference. I will produce an extra subscribers’ only video and essay about Jane Eyre in the interim.

Sorry to be a pain; have you got another link or reference for the Nussbaum work you cite here? I tried clicking the link but it didn't seem to work for me!

A guaranteed way to become unhappy is to spend all your time trying to be happy.