How I learned to love literary criticism.

What makes secondary literature worth reading for the common reader?

When I asked Zena Hitz this question in our recent interview (do listen, she’s full of good things), Zena took her public position of “zero”. Obviously, I do not agree. How could this blog exist if I did? But I don’t think Zena and I disagree as much as it might appear. This essay is an account of what makes secondary literature worthwhile for me. (You might also enjoy Isaac Kolding on this topic.)

When I was at school, I knew a boy who always seemed to have read literary criticism about the books and poems he knew, and so always had clever opinions. I didn’t realise he was reading that stuff, and when a friend told me that he did, his facility for having opinions was explained. He seemed less able to work to his own conclusions and I did not follow his example, though he was a better student than I was.

For a long time, I thought literary criticism was a waste of time. Some of it could be excellent. Christopher Ricks was always my ideal of a critic: someone who did not have extra-literary ideas, but who explained the workings of the poem. Ricks pays close attention to the meaning of words, the logic of thoughts, and the rhetoric of expression. He is, in some senses, a mechanical critic. I was never much of a New Critic—all those supposed fallacies are themselves fallacious, not, in fact, being logically necessary conclusions—but I was a close reader. John Carey’s book on Donne was one of my favourites. These two critics look carefully, but they aren’t scared of history, biography, or common sense.

As an undergraduate, I was under the spell of Harold Bloom, for better and for worse, because I agreed with him about political criticism: everything I saw that was Freudian, feminist, Marxist, or whatever else, was more interested in those ideas than in literature. Many of the people I knew at university who were interested in those ideas would profess to love literature (and could quote it and did in fact feel strongly and so on) but everything was about those political ideas for them. There seemed to be no such thing as literature, only literature as part of a larger political discourse. They simply couldn’t talk about a poem without soon arriving at the same conclusion. It was all a prelude to the real interest.

And yet, I kept meeting people who had not read Descartes, or Plato, or the Gospels, or what you will. These ideas were either drawn from a narrow list of philosophical works or they were draw from secondary works. I had avoided Virginia Woolf for these reasons until a teacher told me Mrs Dalloway was actually a good novel. (A woman teacher, obviously.) And so it was! Later on, I discovered she was the best critic of the twentieth century. Calling her a feminist is like calling Milton a religious poet or Dickens a working-class novelist. True, important, but nothing like the whole truth.

When I started reading New Historicism and other such works, I felt I was right. Unliterary! Political! And so boring I thought my head would roll off! I was luckier than I knew, though, because I was in fact receiving a fairly traditional education at university, and was told to read wonderful books like Shakespeare’s Festive Comedy as well as newer, more Theoretical, less “accessible” works. And I decided I didn’t care very much how compliant I was with Theory. I was there to study the canon and that was am acceptable thing to do, so I did, and damn the rest of it. Contra mundum was my motto. I read Hillis Miller on Dickens and I just didn’t care very much. I wanted Dickens!

Obviously, I had neither the temperament nor the conscientiousness required for academic life, and I went on my way, still chewing through the canon like a caterpillar. I got up early before work to read, covering subjects of which I felt ignorant. The early mornings of my twenties before work were spent with Hume’s Essays, Mises’ Human Action, the works of Lytton Strachey, biographies of John Adams and Edward VII, and with the many novels and poems I hadn’t read yet. I read the Life of Johnson in fits and starts, carrying the book around the country at times. I read Shakespeare on my commute, as well as the lives of the Prime Ministers (some of them).

And I slowly realised that literary criticism wasn’t something to be despised. Who did I love more than the essayists, the biographers, the interpreters? Not just Ricks and Carey (The Force of Poetry and The Intellectuals and the Masses particularly) but all those wonderful Longman editions of the poets, full of careful scholarship from which I had learned so much. It became clear to me that a lifetime of reading the canon would necessitate reading secondary literature. I learned so much from the essays of Michael Hoffmann and Clive James, not least what other books to read. I found Jonathan Bate deeply illuminating about Shakespeare. I began to yearn for a library where I could find the more expensive books.

Books like How Fiction Works or The Artful Dickens are hugely useful. Critics that stick closely to the what and the how of writing—not interpreting, but expositing—make us into better readers. They are like the friend or spouse at an art gallery drawing out attention to the living quality of fabric or the verisimilitude of a wrinkle in a portrait. I have always loved biography, believing with Johnson that it is one of the most enjoyable forms of literature, but I was becoming a reader of criticism too.

When I read Clive James’ essays, I decided to buy a copy of Johnson on Shakespeare—edited by Walter Raleigh, which has only the Preface and the notes. Unlike my unwieldy copy of Johnson’s selected works in the Oxford edition, this was a pocket-sized book I could live with on trains and in the lunch break. It had been five years since I read Johnson’s criticism. Now it came alive in me again, that same sudden invasion of glory I had felt reading Rasselas and the Rambler and the Lives of the Poets. (So many people have told me over the years they find the Lives dull. I find this incomprehensible. It’s like finding out someone doesn’t like cheese. I yearn for the Lonsdale edition.)1 The Preface is one of the best and most significant works of criticism in English (along with Milton’s preface to Paradise Lost, Wordsworth’s preface to Lyrical Ballads, and the various works of Sidney, Shelley, Woolf, Hazlitt, Sontag). I could hardly believe I had neglected it for so long. Why wasn’t I reading it with the attention I was giving to the Life? (Of course, there’s a lot of good criticism in the Life, too.)

I had been dabbling in some of the other criticism I have mentioned here, but now I felt compelled. Johnson on Shakespeare was handed round the office and we discussed his views on our favourite plays. This is what criticism ought to be. A living part of reading. Of course, I was still too ignorant to appreciate some criticism, but I was becoming more discerning.

I was disappointed by The Anxiety of Influence, which is heavy with jargon and makes rococo elaborations out of a fairly simple idea, albeit one which is routinely misunderstood and inaccurately paraphrased. Kermode was a charm. I read Shakespeare’s Language again and again, and got a huge amount of value from books like The Language of Shakespeare by G.L. Brook and Rehearsal from Shakespeare to Sheridan by Tiffany Stern. These works give you information: they help you see what is there on the page: what the words mean, when there are implied stage directions in the language. Each re-read of a play was now a better read, even if not a more interpretative read.

These days, I am more immersed in secondary literature than I have ever been. This year alone I have written about A.C. Bradley, Nevill Coghill, A.D. Nuttall (his New Mimesis was a revelation to me; I adored Shakespeare the Thinker as an undergraduate and keep returning to it), James Shapiro, Will Tosh, James P. Bednarz, and Ted Tregear. Outside of Shakespeare, I have written about the work of scholars like Hollis Robbins, Marion Turner, Ann Pasternak Slater, Helen Gardner, C.S. Lewis, Martha Nussbaum, Wayne Booth, various Joyce scholars, Helen Vendler, Barbara Everett, György Lukács, Northrop Frye (praises! praises be upon him!), and others.2

I don’t expect most readers to read this much criticism: I spent half my life reading, and prioritise the primary works. The whole enterprise of this blog is to bring you some of what helps you become better readers without having to give over the hours required to read something like The Mirror and the Lamp.

But from all of these scholars, I have learned. They impart knowledge with generosity, describe difficulties without conceding ease to mediocrity, and have more respect for the authenticity of literature than the annoying urgency of ideology. I still believe that those people who are primarily politically engaged with literature are not very deeply engaged with either. What I liked about Will Tosh’s book on queer theory and Shakespeare is that he is primarily showing his readers a way of reading Shakespeare, rather than constantly trying to promote a view of society. Of course, he is doing both, and reading Shakespeare like that might make you think differently about social questions, but that thinking remains yours to do, not Tosh’s to insist upon. His book kept, to my mind, the right balance. The same is true of A Thousand Times More Fair, a study of Shakespeare and justice.

The greatest weakness of any secondary literature is the persistent idea that particular ways of reading might change society in specific ways. See, for example, this reductive, smug, and badly informed article about Luigi Mangione’s Goodreads page. If you want to know why the literati are so myopically unable to communicate with their out-group (an impressively growing population), this paragraph is an excellent representation of the problem.

Luigi’s also got Infinite Jest on his to-read list, which made me laugh. He also has Ayn Rand on his to-read pile—marking Rand down as something you hope to read someday seems more troubling to me than reading it. It looks like you got some bad book advice from a Libertarian and were too incurious to question it.

Since when does reading a book not count as questioning an idea? People should read more books from the approved list and we will mock them when they do not, even if the person we are mocking is on trial for murder! Ah yes, there it is, literature’s famous ability to teach you empathy. No, no, no. This will not do. This is the descent from the pathetic to the snobbish. No wonder the author of this piece disowned his own views a few paragraphs later.

The one thing I disliked about Marion Turner’s splendid biography of Chaucer is that she often makes these rather vacuous statements. It’s clear that she is gesturing to a somewhat progressive/left-wing idea of how literature might change our views, but she never says what or how or why. The reader drops suddenly from the heights of scholarship and knowledge to the confusing shallows of ideals taken-for-granted.

Arguments about political, moral, and technological progress are remarkably important, but literary scholars do themselves, and more importantly, their readers, a singular disservice when they make open-ended statements about the political implications of seeing things differently or reconstituting society along more equitable lines. These ideas are owed far more than vague gestures like those made by a wondering pilgrim as he passes a city in the distance. If these ideals really are the Celestial City they are worth visiting with careful attention! Write a new Pilgrim’s Progress if it matters that much. To take such things for granted is a disservice to the reader and to the idea. Who but a fool takes for granted a guide book’s claims before they have travelled to the monument?

Literature is a way of thinking, not a storehouse of conveniently “liberal” conclusions. It is liberal in the greatest and the grandest sense: the free activity of the individual mind, the embodied idea of pluralism, the subordination of the abstract to the panoramic; it is the counterbalance of rationality: it makes imagination the play of reason, emotions continuous with intellect, and puts the reader in the position of one sent to gather flowers—unable to proceed without distraction, never lacking in beauty to wonder at, or wider landscapes to admire, and always able to benefit from the better learning and deeper knowledge of those more familiar with the region.

Good secondary literature works like good primary literature. It starts from the axiom that we must let the book show us how to read it, and is not befuddled with the cant terminology of texts and paratexts and all the other ornamental jargon that slowly converts you away from the gospel and towards the speculative labyrinth of theology.

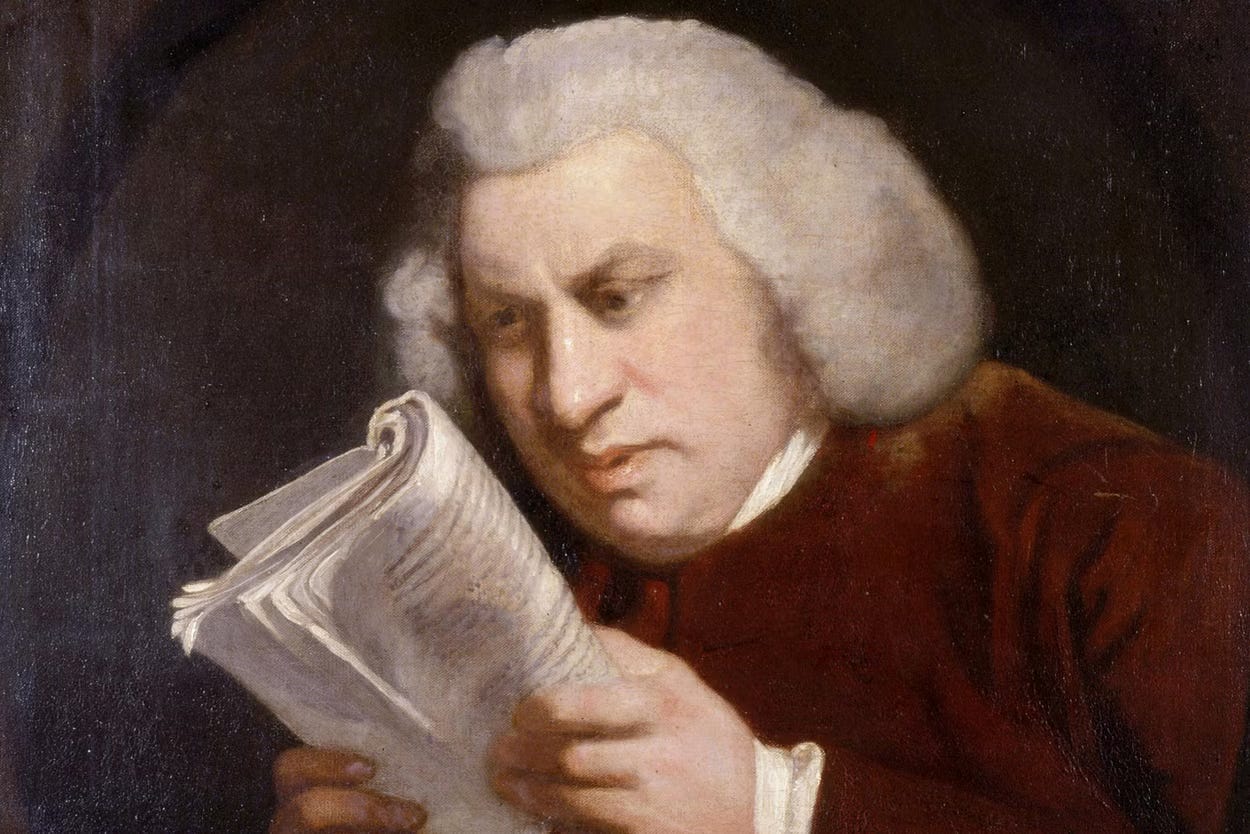

All great literature shares one high purpose: to make us better readers of the great originals. Whatever you read, always remember Samuel Johnson. CLEAR YOUR MIND OF CANT.

Read the Life of Pope. Just do it.

Some of these are critics I have read for book research, so you won’t find them on the blog, necessarily.

‘Later on, I discovered [Woolf] was the best critic of the twentieth century….’

I encourage you to write more on this subject. I’m here for it!

I love literary theory … but the first pass should be on the text alone — apply different lenses after that.