On December 5th, I am hosting a discussion with Shakespeare professor Stephen Greenblatt and psychoanalyst Adam Philips about their new book Second Chances: Shakespeare and Freud.

Antony & Cleopatra contains perhaps Shakespeare’s most famous instance of a poetic speech that is closely based on an original source. When Enobarbus describes Cleopatra, it is based on a passage in Plutarch’s Life of Antony, translated by Thomas North. (In italics are the parts that correspond to North/Plutarch.)

The barge she sat in, like a burnish’d throne,

Burn’d on the water: the poop was beaten gold;

Purple the sails, and so perfumed that

The winds were love-sick with them; the oars were silver,

Which to the tune of flutes kept stroke, and made

The water which they beat to follow faster,

As amorous of their strokes. For her own person,

It beggar’d all description: she did lie

In her pavilion—cloth-of-gold of tissue—

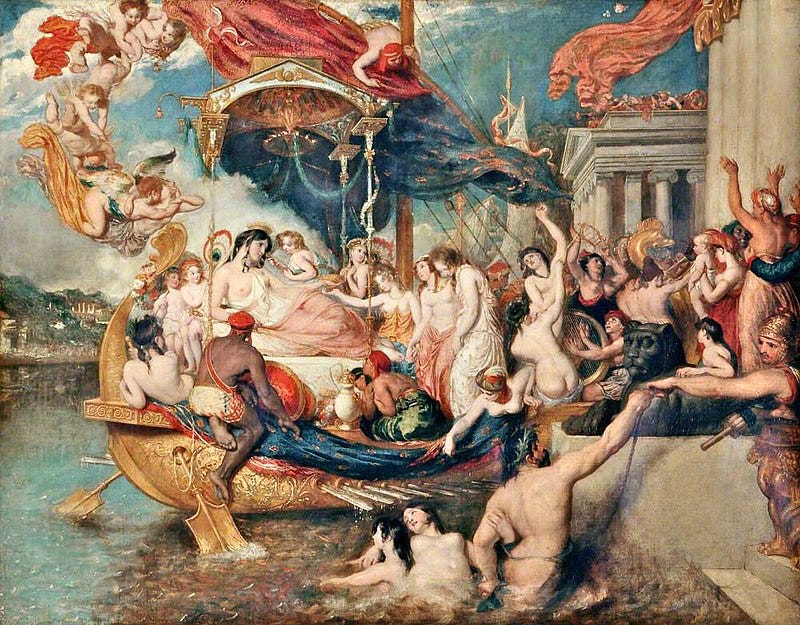

O’er-picturing that Venus where we see

The fancy outwork nature: on each side her

Stood pretty dimpled boys, like smiling Cupids,

With divers-colour’d fans, whose wind did seem

To glow the delicate cheeks which they did cool,

And what they undid did.

What you will notice immediately is that Shakespeare hasn’t taken very much. There’s a general correspondence in the structure, as you would expect, but the language itself is sparsely borrowed.

For comparison, here’s the relevant section from North,

…she disdained to set forward otherwise, but to take her barge in the river of Cydnus, the poop whereof was of gold, the sails of purple, and the oars of silver, which kept stroke in rowing after the sound of the music of flutes, hautboys, citherns, viols, and such other instruments as they played upon in the barge. And now for the person of herself: she was laid under a pavilion of cloth of gold of tissue, apparelled and attired like the goddess Venus commonly drawn in picture: and hard by her, on either hand of her, pretty fair boys apparelled as painters do set forth god Cupid, with little fans in their hands, with the which they fanned wind upon her.

There are two major qualities here: lists and commonplace descriptions. It lacks all poetry. There is very little metaphor. Looking at the differences between the two is a good way to alert us to the extent of Shakespeare’s talents. With his additions, Shakespeare turned the speech into something quite different.

Plutarch/North tells us that Cleopatra “disdained to set forward otherwise”—Shakespeare knows that the imagery and metaphor of the speech will make that quite obvious. Enobarbus wants to have the status of being able to tell these men about Cleopatra: he disdains to set forth his speech with such petty explanations. Having told us of Cleopatra’s pride, a list is sufficient for Plutarch: “ the poop whereof was of gold, the sails of purple, and the oars of silver which kept stroke in rowing after the sound of the music of flutes, hautboys, citherns, viols, and such other instruments as they played upon in the barge.”

This is a heap of facts, little more.

Shakespeare, though, is not a moralising biographer, but a dramatic poet. He goes beyond the merely splendid details. This time I will bold his additions.

The barge she sat in, like a burnish’d throne,

Burn’d on the water: the poop was beaten gold;

Purple the sails, and so perfumed that

The winds were love-sick with them; the oars were silver,

Which to the tune of flutes kept stroke, and made

The water which they beat to follow faster,

As amorous of their strokes.

Watch the progression of sounds, from “b” to “p” to “s”: barge, burnished, burned, beaten, purple, perfume, love-sick, silver, stroke, beat, strokes. (See the double alliteration in the line: “The water which they beat to follow faster”, which neatly echoes the rhythm of paired oars beating the water.)

There is a euphony to the progression of vowel sounds too, especially in the repetition of “ur” and “si”, and in the echoes of “gold” and “oars” and “water”, of the “o” in “stroke” and “follow” and “amorous”, of “perfumed” and “tune” and “flutes”. Notice too that he inverts the order in “purple the sails”, so that it becomes a chiasmus with “the poop was beaten gold”, a rhetorical figure that emphasises how marvellous the barge must have looked, and how dynamic. Lists flatten; chiasmus enhances. It replicates the darting movement of a marvelling eye. Plutarch is a book-keeper next to Shakespeare, who re-enacts the sensation of watching the barge.

Most importantly, Shakespeare adds metaphor. In 1606, James Shapiro describes Shakespeare’s additions as “hyperbolic and eroticised language” which captures the “paradox and allure” of Cleopatra. There is nothing in Plutarch/North that is close to a barge which burns on the water, an image that captures the shimmering reflection of the gold, the heat of the sun, the intensity of Cleopatra against her surroundings, a sense of foreboding, and the inherent nature of her divinity as empress. Where Plutarch/North have purple sails, Shakespeare has them perfumed to make the wind love-sick, an image appropriate to the ancient world in which all sorts of nature spirits inhered in the waters and the winds, but which makes Cleopatra’s appeal stronger and more real by displacing it from simple human description into something that can only exist in poetry, in the imagination. Everything around Cleopatra is made to look amorous—the wind and the water—because of the effect of these erotic paradoxes upon the observers.

Even in simple phrases, Shakespeare can transfigure Plutarch/North. Look at “pretty fair boys apparelled as painters do set forth god Cupid”. North has already used the comparison to a painter with Venus in the preceding clause. Shakespeare turns this into: “on each side her/ Stood pretty dimpled boys, like smiling Cupids”. Replacing “fair” with “dimpled” means he doesn’t need to invoke painters, he can rely on a simile; the art of words is to require the imagination to be a painter. What in North is repetitive and a little cliched becomes in Shakespeare a concise figure that works on our “imaginative force” (HV, prologue). Dimpled does something else, too: it points to how particular Cleopatra is. The boys that stand next to her must be pretty enough to be there, pretty as Cupids to match her as Venus. Dimples capture that, without laboriously spelling it out.

The last two lines are pure Shakespeare and tie-up the whole speech in a way that in inconceivable in Plutarch/North. It describes the wind from the pretty dimpled boys’ fans—

whose wind did seem

To glow the delicate cheeks which they did cool,

And what they undid did.

The paradox is that Cleopatra glows, presumably, with pride, satisfaction, vanity—she is “delicate” in so many ways—as well as with the warmth of the weather. This is the oddness of beauty, of captivation, of royalty: that it exists in perception, in a constant cycle of creation and observation; that the more demanding it is of our attention, the more our attentions can enhance it. Cleopatra is pure charisma; she is what burns at the centre of the barge.

This speech is a minor instance of Shakespeare’s great talent: his sensitivity to all aspects of how the language fits together. It shows us just how much he can do with how little.

would love to hear you talk more about some of the more prominent/ important rhetorical devices a common reader might do well to familiarise themselves with. I'm sure the list would be mostly unsurprising, but your recent discussion of, say, parallelism has been useful for me; a simple device I knew but had been underrating.

This is one of the most succinct and well-drawn illustrations of the distinction between reportage and poetry that I’ve read. As someone who has tried, sometimes successfully, but most times in vain, to have the two meet (and to convince others that it’s worth trying), I’m grateful to have this now to refer to.