The next Shakespeare Book Club is ***Sunday 23rd June, 19.00 UK time***. We will be discussing As You Like It. There will then be a summer break. I update the schedule for Shakespeare here. All Shakespeare posts are here. (These links work better in your browser than in the Substack app… I don’t know why.)

Pastoral doubleness

Shakespeare’s primary mode of thought was opposition: contrasts, doubles, juxtapositions. As You Like It caps the long period of his romantic comedies (Love’s Labour’s Lost, Much Ado About Nothing, A Midsummer Night’s Dream) with the classic duality of Elizabethan poetry: the pastoral. Pastoral pairs the country and the city: the country is natural, a place of love, a virtuous scene; the city is artificial, a place of lust, a wretchedly political environment. The country is romance; the city is satire.

Everything in the forest is reversed: there is an alternative Duke, an alternative clown, foresters not courtiers, Ganymede not Rosalind. The contrast is played out directly in the dialogue between Touchstone (city jester) and Corin (forest fool). But think, too, of this play being performed at court: the duality of city and country, court and forest, would be literally true of the courtly audience sitting in front of the wooded stage. One use of pastoral, therefore, is to comment on the city in disguise.

We can see Shakespeare playing with both ideas and genre in this opposition. These are old themes—artifice and nature, corruption and decency, town and city, romance and satire—given very modern Elizabethan resonances. But as Frank Kermode says in Shakespeare’s Language, we should not expect this play to “draw a simple diagram” of these dynamics.

Out in the forest, the shallow artifice of conventional city poetry is shown up as lacklustre and bare. In the city, the highly artificial satires of Jacques and Touchstone are sophisticated and entertaining, but in the pastoral forest truth is valued more than sophistication. In all of these contrasts, Shakespeare is asking us to consider, who is the real fool, the natural simpleton or the overwrought urbanite? When Jacques walks in saying “A fool, a fool, I met a fool in the forest”, we wonder who he means.

And responding to the literary scene of its time, at the heart of As You Like It is the paradox that “the truest poetry is the most feigning.”

Rosalind: anti-cliche.

In his previous comedies, Shakespeare included a lot of sonnets. As You Like It has fewer, and hardly any appear in his plays after this. Some of his private sonnets were published in 1599, without his permission. He seems unwilling to have given any more material to the pirate publishers. But in As You Like It he also heightens his satire of sonneteers. The Petrarchan mode of distant maids with cold hearts and fierce eyes had become stale, repetitive, cliched. Orlando’s poetry is representative of this tired tradition. Phobe mocks it by taking it literally, frustrated and piqued by the empty conventions of love-writing. Reacting to the trope that a woman can kill with a look, she lets fly a poetic stream of invective

Thou tell’st me there is murder in mine eye:

’Tis pretty, sure, and very probable,

That eyes, that are the frail’st and softest things,

Who shut their coward gates on atomies,

Should be call’d tyrants, butchers, murderers!

Now I do frown on thee with all my heart;

And if mine eyes can wound, now let them kill thee:

Now counterfeit to swoon; why now fall down;

Or if thou canst not, O, for shame, for shame,

Lie not, to say mine eyes are murderers!

Kermode finds that so much of the play, being concerned as it is with the literary scene of 1599, has “slipped over the horizon”.

But it persists in popularity because of the indefatigable presence of Rosalind, who has a greater share of the lines than even Cleopatra. One reason for the relative silence about As You Like It in its immediate posterity (no quarto editions, no commentary for at least a century), is, as James Shapiro says in 1599, the fact that Shakespeare created, in Rosalind, a very realistic character. Audiences must have been bemused. This was something quite new. As Proust describes in Within a Budding Grove, truly original art must make its own posterity, educating its audience in its innovations. That is what had to happen here. Once the topicality of the literary debate in the play recedes we are left with Rosalind: witty, inexhaustible in debate, commanding, loveable, pragmatic, argumentative, charming, for who no other character in the play is a match.

That is why, despite the difficulty of understanding all the literary satire, As You Like It retains its popularity today. Rosalind is forever enchanting. Just think what it meant, in 1599, for a boy actor playing a woman (who was in turn disguised as a man, and then pretended to be a woman again) to speak “like a saucy lacky” to Orlando, to lecture him on love and history and morals. And the marriage scene is truly radical. Orlando and Rosalind speak legally binding words—a rare enactment of a sacrament on stage, something which was technically banned.

So Rosalind is the walking embodiment of all that is wrong with Petrarchan poetry. She is nothing like those false, idealised women. She is the anti-cliche. And that still discombobulates us today.

“by lies we flattered be”

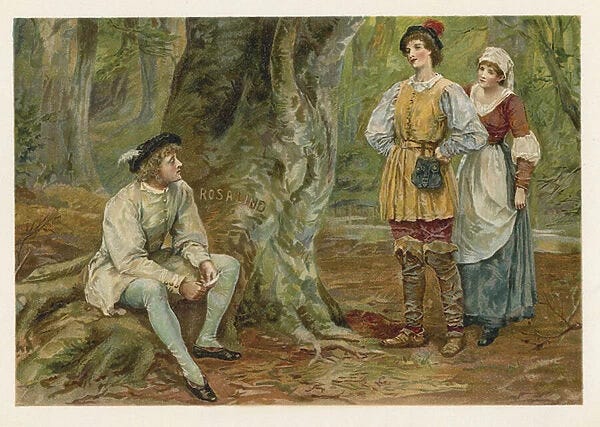

The plot is simple: Rosalind sees Orlando at court and they fall in love; she is banished and flees to the forest; he follows; they meet. But Rosalind goes in disguise as a man, Ganymede. She uses that disguise to tutor Orlando in the ways of love, to stop him writing mindless poetry and to see her for who she really is. This enacts the irony of the phrase “the truest poetry is the most feigning”. Rosalind must be disguised for Orlando to know her properly.

The central question of the plot is: why doesn’t Rosalind cast off her disguise as soon as she knows Orlando is in the forest looking for her?

It would be so simple. The lovers meet in the forest, free from courtly convention, and return betrothed. Why maintain the disguise? The answer is that Rosalind, like Jacques, has met a fool in the forest. Orlando’s idea of love is conventional, romanticised, Petrarchan, silly. “If I could meet that fancy-monger, I’d give him some good counsel,” Rosalind says. And she does.

In Sonnet 138 (published, in an early version, in the pirated book of 1599), Shakespeare wrote about the dynamics of romantic relationships with “simple truth suppressed” so that “by lies we flattered be”. The speaker of the sonnet says of his mistress, “I do believe her, though I know she lies” because he wants her to think he is naive and inexperienced, “Unlearnèd in the world’s false subtleties.” He knows she is unfaithful; likewise “she knows my days are past the best.” Why this mutual deception? Because that is how the truth can be safely acknowledged without hurt feelings. “Oh, love’s best habit is in seeming trust,/ And age in love loves not to have years told.”

We are far from the Petrarchan stereotypes here. Phoebe might find it harder to object to this sort of dishonesty — because it is not fanciful and silly, but a lie that tells a deeper truth, a series of hints, subtexts, and shared understandings. This is the dynamic Rosalind must establish with Orlando: she needs the subtlety of the city coupled with the simplicity of the forest. As Shaprio says,

Paradoxically, the only way Shakespeare can show that Orlando has matured in his understanding of love is to show him masking what he’s learned, having him playing and lying in love, learning to appreciate Rosalind’s deception.

To get to him to see her not as a Petrarchan cliche—a woman whose looks can kill, a distant, cold maiden, a collection of tropes not a real, living woman—, Rosalind must create a new set of artifices, ones that show him the truth. A woman’s wit, she warns him, can never be suppressed: shut the door and it flies out of the casement, close the casement and it escapes through the chimney. You cannot contain Rosalind within the idealised restrictions of conventional love poetry. The earnestness of Orlando’s feelings is not enough.

“The boy is fair”

So, the crucial question for performance becomes: when does Orlando realise that this is a game, that Ganymede is Rosalind? Surely quite early on. Multiple references are made to how pretty and feminine Ganymede looks. And remember, Phoebe falls in love with Ganymede because of her eyes (“the eyes of man did woo me”). There’s no disguise for that. When Oliver meets Ganymede he says,

If that an eye may profit by a tongue,

Then should I know you by description;

Such garments and such years: “The boy is fair,

Of female favour, and bestows himself

Like a ripe sister.”

Surely, Orlando told him this. When Rosalind meets the wounded Orlando—still in male disguise—she says, “I thought thy heart had been wounded with the claws

of a lion.” His reply?

Wounded it is, but with the eyes of a lady.

Now, remember what Orlando said to Rosalind right at the start, when she was Rosalind, trying to petition the Duke to stop the wrestling match: “let

your fair eyes and gentle wishes go with me to my trial.” Is he then supposed not to see her eyes when she is in male disguise in the forest?

No! He knew! He knew from very early on! Maybe it strikes him as uncanny rather than obvious. Maybe he “knows on some level”. Maybe his obsession with the remote ideal of Rosalind in his poetry means it takes him some time to realise what he is looking at.

But it is the oldest cliche in the book that men fall in love with women’s eyes. The first time they meet in the forest, when she is disguised as a man, the dialogue is strange. Within a few lines Orlando says “Where dwell you, pretty youth?” Then he questions her courtly accent. It doesn’t take much imagination to see the whole dialogue as having a knowing undertone. “Fair youth,” Orlando says, “I would I could make thee believe I love.”

Is this, then, like Shakespeare’s sonnet, a relationship where “simple truth suppressed” sets the dynamic from the start?

Wise fools in the forest

Let me close with one final thought to suggest that Orlando has some sense of Rosalind’s disguise from the beginning. Shapiro points to the marriage scene as the moment when Orlando irrefutably realises Ganymede is Rosalind. How could he hold her hand and not realise she was a woman? Agreed; but to create the right sort of dramatic tension, he must suspect, he must intuit, he must look at Ganymede and wonder what those eyes remind him of. He says in that initial forest dialogue, “I swear to thee, youth, by the white hand of Rosalind.” Are we so sure he doesn’t take her hand at that point?

Her response could be spoken many ways, one of which is, in a moment of shock, to realise that the game is slipping: “But are you so much in love as your rhymes speak?”

That is the moment when the two of them realise this is not a mere flirtation, this is not just city lust—this is the true love of the forest. Hence Orlando’s simple, unpoetic response. “Neither rhyme nor reason can express how much.”

They know. They fled to the forest, away from the artifice of the court and they immediately knew. But realising love so suddenly is a powerful thing. Rosalind must be sure. If she casts off her disguise immediately she will be trapped as the conventional woman. Her wit will be constantly squeezing into nooks and crannies. She, faced with Orlando’s sudden, innocent, naive admission, as he looks into her eyes, she sets the game afoot: “Love is merely a madness, and, I tell you, deserves

as well a dark house and a whip as madmen do.”

They must suppress the simple truth in order understand each other properly. The forest is the only place where that is possible. The retreat into pastoral simplicity is revealed to be a parallel universe, a dream world, a place where the truest poetry is the most feigning.

To become wise lovers, they must be fools in the forest first.

“To become wise lovers, they must be fools in the forest first.” 💯 nonetheless where is that forest that we can go to ? To be the fools first ?

I did read your essay - and enjoyed it - but I don't see how R's deception prompts O to see her. Apologies for missing the point.