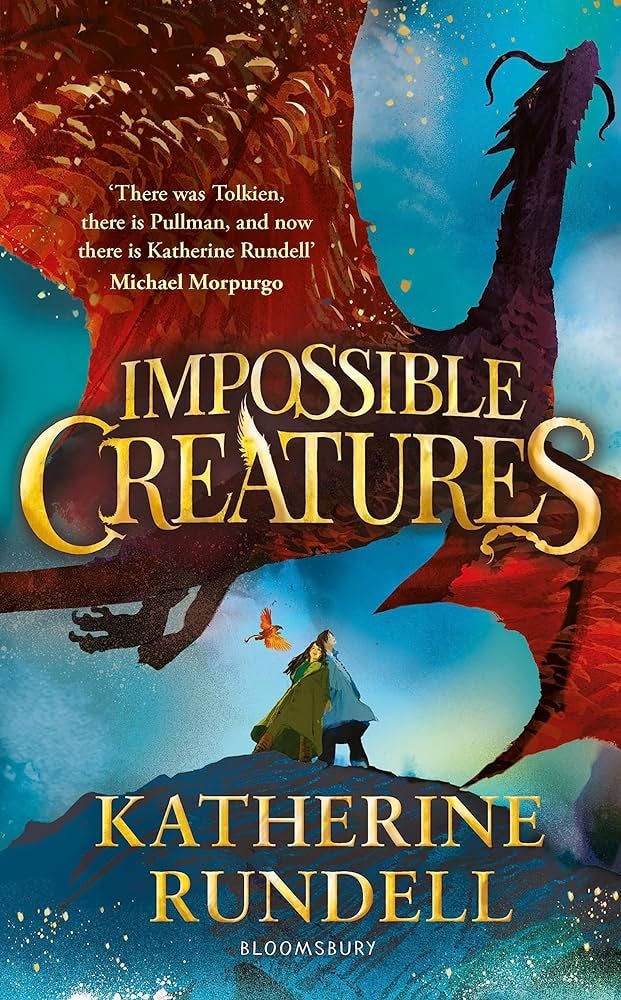

Impossible Creatures, by Katherine Rundell

Good but not that good

Katherine Rundell is undoubtedly one of the best writers now at work. Whether writing about moles, seventeenth century poets, or a group of children who have to survive in the Amazon after a plane crash, she has the ability to get readers of all ages to turn the page. And her young fans are devoted. I have lost track of how many times my eight year old daughter has listened to Rooftoppers. When she read The Explorer she was completely lost to us, apart from those moments when she popped up from behind the book to divulge shocking plot twists. They ate tarantulas! To many readers, including me, Rundell’s books are places of wonder, the sort of books we all remember loving as children.

So it is little wonder that Impossible Creatures has done so well: an instant bestseller, the Waterstones Book of the Year, adulatory reviews saying her work is the equal of anything in Narnia or Philip Pullman. And Rundell uses her fame for laudatory ends, speaking out against the over mighty celebrity authors who dominate children’s fiction, calling for more variety to be presented in bookshops. Rundell is right. Britain has produced many children’s classics and we shouldn’t crowd them out with celebrity trash. Throw in that Rundell is an accomplished academic, the youngest woman to be made a Fellow of All Souls, and you have a splendid role model. What parent can resist?

And yet, the comparing of Rundell to Tolkien and Pullman (not just in reviews, but on the cover too) is over hasty. I say this as an admirer. Impossible Creatures is good, but it’s not as good as that. We do not take Rundell seriously as a writer by blithely comparing her to the permanent accomplishments of children’s literature. Tolkien, Pullman, and Lewis wrote fantasy, and that is where Impossible Creatures is weakest.

Many of the fantasy elements of Impossible Creatures feel more stated than created. Calling the islands where the mythic animals live “the archipelago” is too literal, clearly derived from Ursula K. Le Guin. The name lacks a real sense of place, of otherness. The name Earthsea has an enchanting quality; archipelago does not. The grandfather is called Frank Aureate, a name meaning golden, which Susannah Clarke used to describe ancient Aureate magicians. There is something of a reality we can go into here, but it is far less absorbing than, for example, the wicked uncle in The Magician’s Nephew. Ditto calling the guardians “Immortals”. Samuel Johnson defined fantasy as “bred only in the imagination.” Too many aspects of Impossible Creatures were bred elsewhere.

Similarly, the various “impossible creatures” of the archipelago are a little crammed in, and come and go so frequently it is hard to keep track of more than the names. The bestiary at the front is a nice touch, and fun to look it with children, but is almost an alternative to the fiction. Merely to identify and describe the mythic creature Ratatoskr goes no further than the children’s book Mythopedia which contains a very absorbing account of Ratatoskr. (Indeed it is a familiar creature from many books, comics, and video games.) Impossible Creatures would be just as exciting, perhaps more so, with fewer of the mythic beasts interloping into the narrative.

Instead, this is an adventure story, as Rundell’s other books have been. And that is what makes it so popular. The familiar elements are all here. The puzzled middle-class boy who stumbles into wonder at a strange new world; the rambunctious slightly wild girl who displays daring in the face of peril; the into-the-woods setting, and the chase of danger. It is a book where children are taken seriously, one of Rundell’s virtues. Here is a representative passage of one breathless moment, written with one of Rundell’s most representative techniques: repetitious excitement.

His first instinct was to run home to his grandfather. But then from the top of the hill there came a noise: a high, peeping cry. It was a desperate, terrible noise: the noise of something struggling to live.

He hesitated only for a second; and then he sprinted, faster than he had ever run, up the forbidden hill.

Rundell’s use of peeping to mean “high-pitched” is unusual, the sort of thing that garners her a reputation as a “literary” children’s writer. But what she really excels at is something much plainer. In two sentences Rundell mentions the cry four times, repeating “noise” three times. A scene like this can be done well or badly, depending on how carefully the balance is got between drama and melodrama. Getting the scale of the intensity right is what makes Rundell such a good writer—not her glancing use of “peeping cry”, but her ability to write adventures that are so good you hardly notice that’s what she’s doing.

To keep company with Tolkien and Pullman, though, or Ursula Le Guin and Diana Wynne Jones, writers Rundell has identified as inspirations, requires a different sort of writing. Rather than write in the mode of what, in ‘Of Fairy Stories’, Tolkien called making a Secondary World, Rundell more often writes in the style of someone like Arthur Conan Doyle, more adept at the drama of adventures than the otherness of fantasy.

Most men, if their grandson burst into a room dripping water and clutching a mythical creature to their chest, would begin asking questions. But Frank Aureate was not most men.

Good stuff, as far as it goes, and familiar from Rundell’s other books, and from the genre as a whole. But this reliance on tropes puts Rundell in conflict with another common idea about her work, this time her own: that she is modern and inclusive.

Frank Aureate has an unreadable face, drinks deeply from his whisky glass, and sits broodingly in his armchair, the old man who has kept magical secrets from his grandson. Readers may feel like they’ve met him before. In Rooftoppers Charles is eccentric and unbound by convention, also a whisky drinker, who strides around in scholarly distraction proclaiming the value of Shakespeare and classical music. In The Good Thieves, the innocent old man who is swindled by a nasty crook is a faded member of the British gentry, whose charming old castle is crumbling, where valuable jewels are hidden in the tower.

And so it goes. Whenever we encounter a strong female lead in Rundell’s novels—and there are several, of diverse backgrounds and characters—we will also encounter a charming, inscrutable, enticing member of the upper classes, familiar to readers of all classic children’s fiction. Inherited money is given an easy pass; characters who got rich by their own lights are more likely to be crooks. In her widely-read London Review of Books essay about reading children’s fiction as an adult, Rundell praised the quiet tradition of radicalism in children’s writing, such as the sly Fabianism of E. Nesbit’s work. But Rundell herself often reverts to the traditionalism of The Wind in the Willows or The Hobbit, relying on the deep roots of English social realism.

None of this matters very much, and hardly seems likely to affect the young readers (presumably the number of people who became Fabians after reading Nesbit is zero?), but Rundell’s persona is of a novelist trying to defend left-wing liberal values. Why You Should Read Children’s Books begins as a defence of fiction, largely consistent with what Tolkien wrote, and ends as a Guardian editorial, bemoaning library funding and the fact that so many children’s novels don’t contain the sort of characters that modern British children can identify with, demographically, ethnically, and otherwise. But in Rundell’s novels, we are just as likely to find charming young girls from nice families with cello playing mothers as we are to encounter one of the children Rundell meets on her school visits. Indeed, her fictional world, which has larders and patrician grandfathers and circus people and old houses, often feels like the past (indeed often is set in the past).

Where Rundell aims to make children feel the importance of the environment, the excitement of nature, the necessity for kindness, she succeeds. She has said children’s literature can “teach the large, uncompromising truths that we hope exist.” And ideas like “love will matter, kindness will matter, equality is possible” come across strongly, in Impossible Creatures as in other works.

But, politically, her stated aims are not quite her results. The charm and high-accomplishment of Rundell’s work is that she often writes like classic authors, not modern ones. In The Explorer, Fred’s father cannot look after him properly because “the firm needs me” and Fred has a “headmaster”, both curiously old-fashioned ways of speaking in 2017. This father character is so out of date he might as well be in a J.M. Barrie novel. In The Good Thieves Rundell writes inclusively about children from a range of social backgrounds, but her heroine is appalled at the idea of spitting. Equality is one thing, vulgarity quite another. When Charles says, in Rooftoppers, that people who care too much about money have “flimsy brains” it is impossible to forget that Charles inherited his nice, large house.

Being an independently minded child in Rundell means being forthright, but never vulgar. Being a feminist character means wearing trousers or learning geography, but not talking about science. Never ignore a possible, Charles’ mantra from Rooftoppers, stands as a motto for all of Rundell’s work, but, for all of that spirit, she frequently reverts to the tropes of classic writing. Impossible Creatures, draws on similar tropes and faces a similar limitation. Rundell’s radical ideas are well disguised in her establishment trappings.

Most surprising, though, for a writer so interested in the scope of language and the inventions of poetry, is that Rundell repeats herself. Throughout her non-fiction and articles, words like “urgent” and “glavanic” are frequently repeated; no intensifier is too intense for a scholar of John Donne, and rightly so; Rundell’s advocacy for poetry is some of the best available from any critic writing today. But this instinct for repetition can be a curse in fiction. When Christopher and Mal first meet in Impossible Creatures, a point when the story starts opening up, Rundell drops into LRB speak.

And then she spoke the most powerful and exhausting, the bravest, most exasperating and galvanic sentence in the human language.

As well as the peeping quality of this language, there is something flattening about the sheer amount of intensity attempted here. Rundell’s academic appreciation of the radicalism in E.Nesbit often tips over into this sort of authorial calling out to her readers—look, here is something vitally important about life you must urgently know, now. Children enjoy being spoken to like adults, but they enjoy more the careering of unicorns unexpectedly out of bushes and the vomiting of griffins over unsuspecting children. When Rundell describes stars as “ambulatory” or says a child is “the burning opposite of sorry” adults feel the charm of a writer treating children seriously. But the best moment in her work are not these, but rather moments likes this:

But Mal suddenly gave a horrified cry. Christopher turned: the man with the knife stood at the far edge of the field.

“Run!”

The more Rundell veers away from hectic adventuring to invocations of powerful, exhausting, bravery, the less galvanic her actually writing becomes. The adults who praise her work enjoy this sort of editorialising, but it is hardly what will put her in the class of Tolkien and Pullman. It is her judicious use of “suddenly” at moments of high pitch that makes Rundell exciting to read, not her sub-Joycean descriptions of the night sky.

Rundell is a splendid writer, to be read by adults and children alike, but the praises she receives too often distract from the real qualities of her work, the unradical, story-telling capacity she shares with all great children’s writers, regardless of their politics. Rundell’s fans are still enthusiastic, and rightly so, but they care most about the fact that in Rooftoppers the children eat off of books, that in The Explorers a sloth does a poo on a child’s lap, or that at any moment, something exciting, unexpected, and dangerous might come round the corner. Rundell teaches that love is real and equality is possible, but more than that she teaches that the best stories happen in entirely their own way. Impossible Creatures almost does that, but not quite.

Thank you so much for writing this and articulating what I was feeling wasn’t sure how to express when I was reading Impossible Creatures - which I didn’t finish. I thought I was going mad given my reaction to it compared to the how it was positioned and framed.

I really liked Rundell's non-fiction in the LRB (the pieces that were collected into the book The Golden Mole) and I loved Super-Infinite, but I was surprised to find that I wasn't that into The Rooftoppers, so it's interesting to read your take. There was something mannered about it that didn't feel real to me. Fantasy isn't real, of course, but it has to have its own solidity. (I think of someone like Joan Aiken, who was a master at that kind of parallel-history magical realism.) And, as you allude to, overt moralising in children's books has to be handled with care.