Is the plain style the same as minimalism?

They fired guns of distress, but were not heard

The next Shakespeare bookclub is SUNDAY 19th May, 19.00 UK time—You can find all the other Shakespeare posts here. I’ll send a link over the weekend.

Earlier this week, I showed you some examples of how the plain and ornate styles have been used in English, and how it can be effective to switch between them. Today I am going to present some examples of the plain style being used in maritime non-fiction of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. What I hope to demonstrate is that the plain style can be highly affecting and greatly dramatic. Sometimes when you have a very powerful, compelling subject the best prose is the plainest.

But, this doesn’t mean minimal or over-simplified. One thing you will notice about these extracts is that, unlike the modern plain style, they are elegantly composed and finely balanced; the sentences are artfully structured with complex punctuation. The standard advice today is to make everything short, to break sentences down with full-stops (periods). But these travellers and navy men, who were writing for the public, didn’t need to do that in order to maintain a splendid plain style.

Perhaps it is true that audiences today require short sentences. But the idea that everyone’s attention span is getting shorter is abysmally stupid. If the claims made were true, no-one would be able to concentrate for long enough to take them in, let alone evaluate them. The whole genre of “attention span” writing is well-designed to flatter that audience that their attention spans aren’t the problem, or that if they are bad at concentrating, it isn’t their fault. It’s not you, it’s your evil phone! No, we are not writing short sentences because of a lack of attention, but because they fit better to the medium of the internet and because most news works best in headline form.

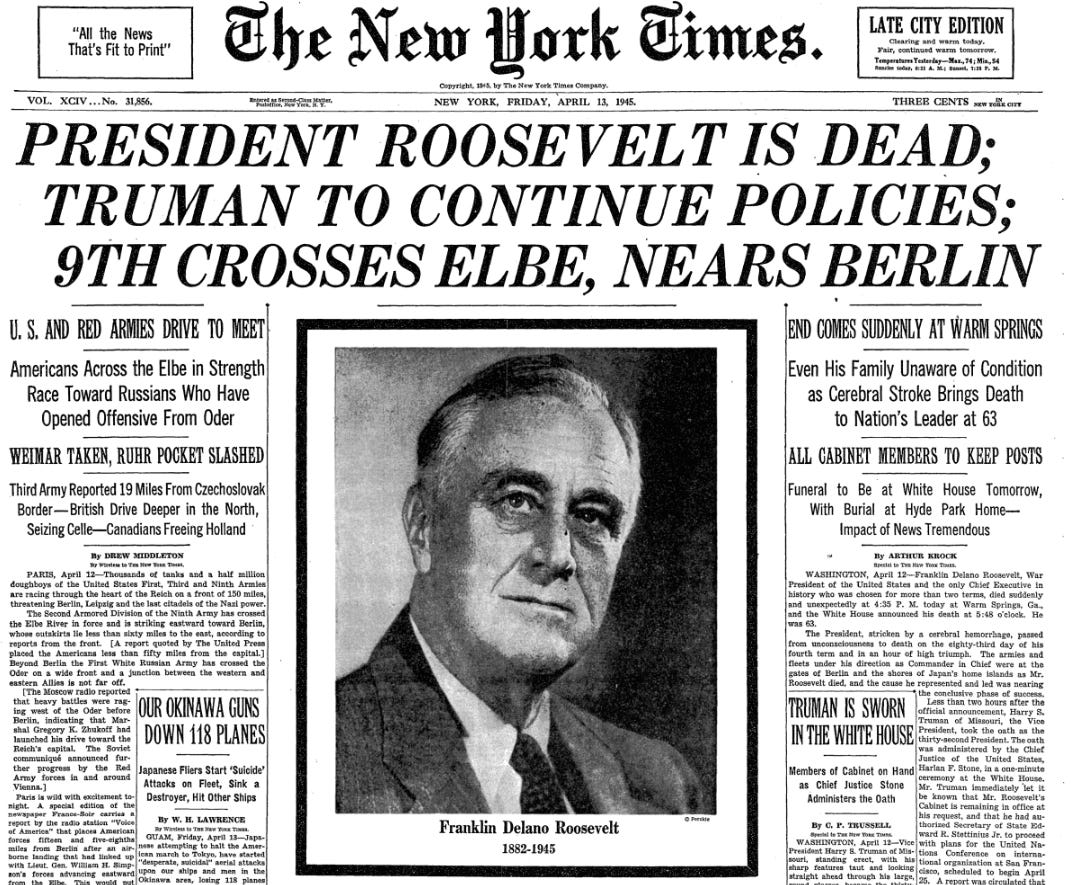

Look at this front page of the New York Times from 13th April 1945. What a masterclass in headline writing. I count fifteen. Each a marvel.

It wasn’t Twitter that invented this sort of thing. Telegraphing the news is literally centuries old. Scarcity of paper necessitated this form of writing long before that too. Genghis Khan and his men were illiterate: messages were sung and in that way spread through the vast troops of horsemen. Once you knew the melody is was easy to fit short messages to it and thus make them memorable.

But, the rest of us do not have to be staccato all the time. It doesn’t suit the purposes of all writing.

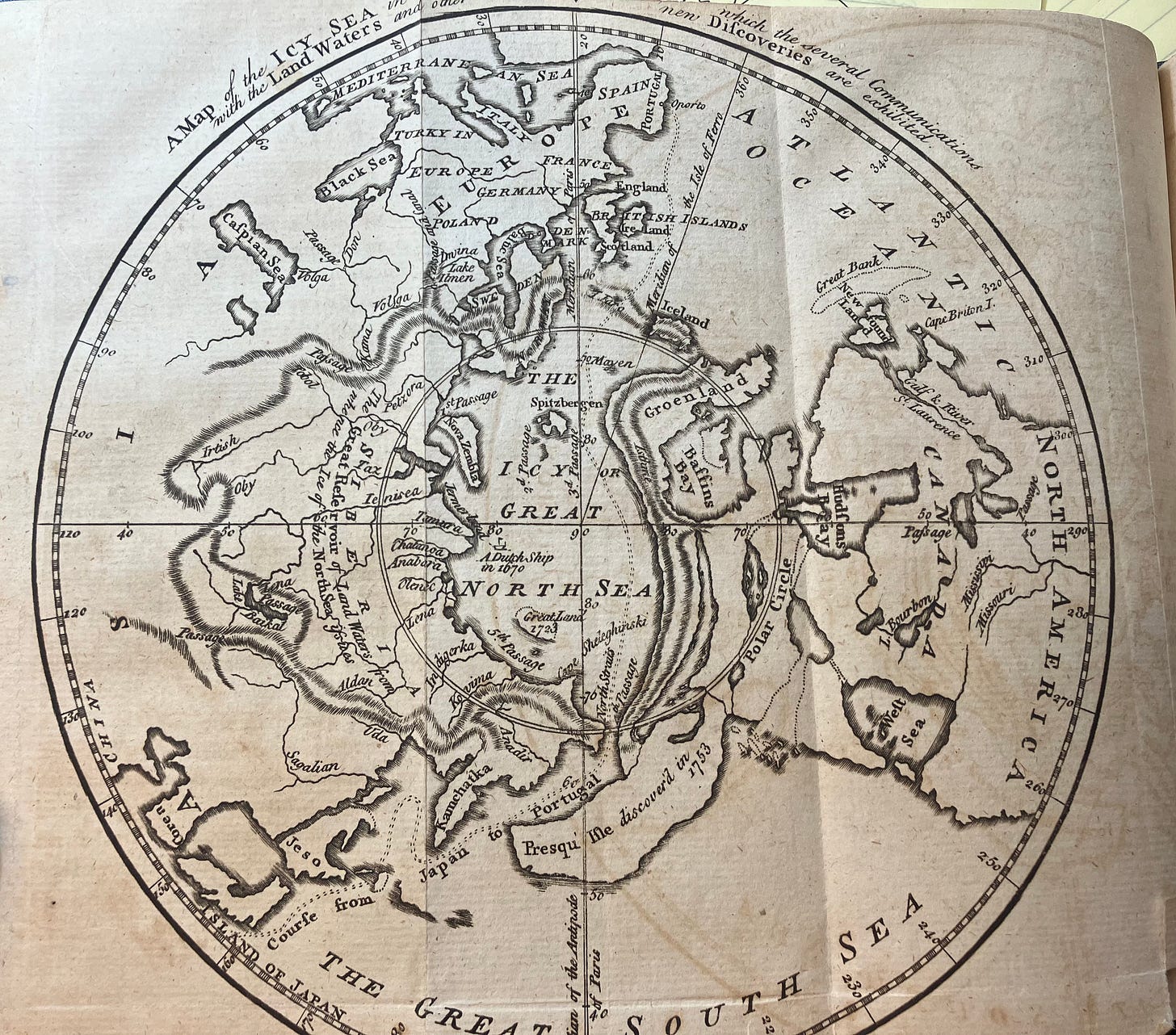

Here is a passage from the ‘Biographical Memoir of the Right Honourable Lord Nelson of the Nile, K.B.’, published in the Naval Chronicle in 1800. It describes a journey through the “polar circle”, i.e. the arctic, and in this section the ship is beginning to face difficulties after being caught in the ice. (The aim was to find a trading route that went over the arctic and would thus save time relative to travelling round the Cape of Good Hope; they failed, as many had done for centuries before them.)

The passage by which the ship had come into the westward had closed, and a strong current set in to the east, by which they were carried still further from their course. The labour of the whole ship’s company to cut away the ice proved ineffectual; their utmost efforts for a whole day could not move the ship above three hundred yards: in this dreadful state they continued for near five days, during which Mr. Nelson, after much solicitation, obtained the command of a four oared cutter raised upon, with twelve men, constructed for the purpose of exploring channels, and breaking the ice: thus did his mind at this early period glow with fresh energy at the sight of danger.

There is so much to love in this writing. It’s plain, workmanlike qualities are well-matched to the scene it describes: one of repetitive, fruitless, labour. It makes no bones about repetition (by which, by which), or “verb enrichment”, or any of the other silly pettifogging ideas modern editors were taught at school and blindly follow with no ear for rhythm and no sensibility for mood. Perhaps the section that is least modern is when the sentence “runs on” after the words “five days.” Every modern editor would insist on a new sentence here. But, it is so important to look at this and see why it works. If you are in the arctic, where it is light all the time, trapped in the ice, constantly working to break out and never succeeding, then the phrase “during which” is far, far more effective a way of continuing the scene than a full-stop. A full-stop would simply kill the atmosphere. It would be crude, ungainly, and cloth-eared. So we have a very nice prose style and the ability to keep a sentence going, like an iceberg floating on the tide. Note, too, the absolutely splendid colon: it does just what a colon ought to do: as Fowler said, it delivers the goods that were invoiced in the previous clause. The style is immediately elevated, too, for the romantic conclusion, a nice break out of the plain style just as the writing breaks out of narrative and into judgement.

Here’s a sentence from a 1773 account of an arctic voyage undertaken more than a century earlier, in the time of Charles II.

One thing remarkable in his relation, and which seems to contradict the report of former navigators, is, that the sea there is salter than he had tasted it elsewhere, and the clearest in the world, for that he could see the shells at the bottom, though the sea was four hundred and eighty feet deep.

I imagine we would write that as at least two sentences, most likely three. But look once again at how well suited to both the newness of the information and the fact of the depth of the sea the continuity of the single sentence is, reflecting in its structure the sense of gazing down into remarkably deep clear water: the revelation of the shells, and the depth, at the end, only works when the sentence is written like this.

This description comes from further on.

It should seem likewise, that the ice frequently changes its place in this latitude; or that it is more solid near land than in the open sea; for, on the 23rd June 1676, Capt. Wood, being more to the eastward, fell in with ice right a-head, not more than a league distant. He steering along it, thinking it had more openings, but found them to be bays… In some places he found pieces of ice driving off a mile from the main body in strange shapes, resembling ships, trees, buildings, beasts, fishes, and even men. The main body of ice being low and craggy, he could see hills of a blue colour at a distance, and valleys that were white as snow. In some places he observed driftwood among the ice. Some of the ice he melted, and found it fresh and good.

There is an especially misguided piece of writing advice that gets passed around on-line which says that you ought to vary your sentences lengths. A long opener pulled up hard by a quick short sentence, and so on. This is total amateur nonsense, propagated by people who think prose style can be hacked in the same way some people think they can find patterns in the markets that predict share prices. Look at the passage above: a good sentence fits its subject matter and if that means you don’t vary your basic sentence length very much, so be it. The variation comes from the content, not from any supposed “rule” of good writing.

Imagine the unspeakable diminishment the King James Bible would suffer if this sort of managerial philistinism were to be applied to it. If you follow rules like that you are thinking of prose as something akin to a pop-song formula. There is some truth hidden inside this idea, namely that sentences should be varied according to the natural variation of the material; but as we have seen here, changing the structure of your sentences is a change in your material: shortening for its own sake is the pretence of intelligence, not its practise.

Too often, we allow conceived notions (falsely presented as rules or insights) to determine the structure of our prose. But the plain style works best, as in these examples, when it its structures are matched to its content. My notes are incomplete, but so am going to close with a fragment that demonstrates what I mean. Anyone who edited this to make the sentences shorter, more varied, to add verb enrichment, or any of the other modern ideas, would be making it much worse, even as they made it more “accessible.”

…Prosperous bore down upon the Speedwell, crying out, ice upon the weather-bow, on which the Speedwell clapt the help hard a-weather, and veered out the main sail to ware the ship; but before she could be brought too on the other tack, she struck on a ledge of rocks, and struck fast. They fired guns of distress, but were not heard, and the fog being so thick, that land could not be discerned, though close to the stern of their ship; no relief was now to be expected, but from Providence and their own endeavours. In such a situation, no description can equal the relation of the Captain himself, who, in the language of the times, has given the following full and pathetic account.

“Here, says he, we lay beating upon the rock in a most frightful manner, for the space of three or four hours, using all possible means to save the ship, but in vain, for it blew too hard…”

I have been following this discussion of plain and ornate styles with interest. Writers do switch between them as necessary. And not just good ones. Edward Bulwer-Lytton – the writer after whom a bad-writing contest is named – did so. His thoroughly researched historical novel, Harold, The Last of the Saxons, was written a consciously literary ornate style, but the extensive appendices were written in plain style. Jumping back and forth between them was a bit of a shock.