Jane Austen's first biographer

celebrating a masterpiece

Before 1938, Jane Austen had no proper biography. This was rectified by the novelist Elizabeth Jenkins (1905-2010), who also became one of the early members of Dorothy Darnell’s Jane Austen Society, and helped with the restoration of Austen’s house at Chawton, which was purchased for the society by Mr. T.E. Carpenter.

Jenkins was a young novelist obsessed by Austen. She had read all the available books about Austen. There were plenty of Jane Austen and her World type books—and the very partial biography by Austen’s great-nephew, which is a memoir really—but she could never find what she wanted: a fully researched, chronological biography that dealt seriously with the novels. So she wrote it herself.

Jenkins had already written the first biography of Lady Caroline Lamb (which the poet James Kirkup called “deliciously ‘period’”, praising Jenkins’ ability to write in the prose style of Lamb’s time) and had won the 1934 Femina Vie Heureuse Prize for her dark and disturbing historical novel Harriet, beating Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust, and Antonia White’s Frost in May.

The Austen biography was her breakthrough. It remained the standard account for years. In many ways, when we think of Jane Austen, we still think of Jenkins’ Austen—a charming, intelligent, robust Englishwoman. Jenkins is the bedrock of what Hermione Lee once called “the English tradition of sympathy and affection for Jane Austen.”

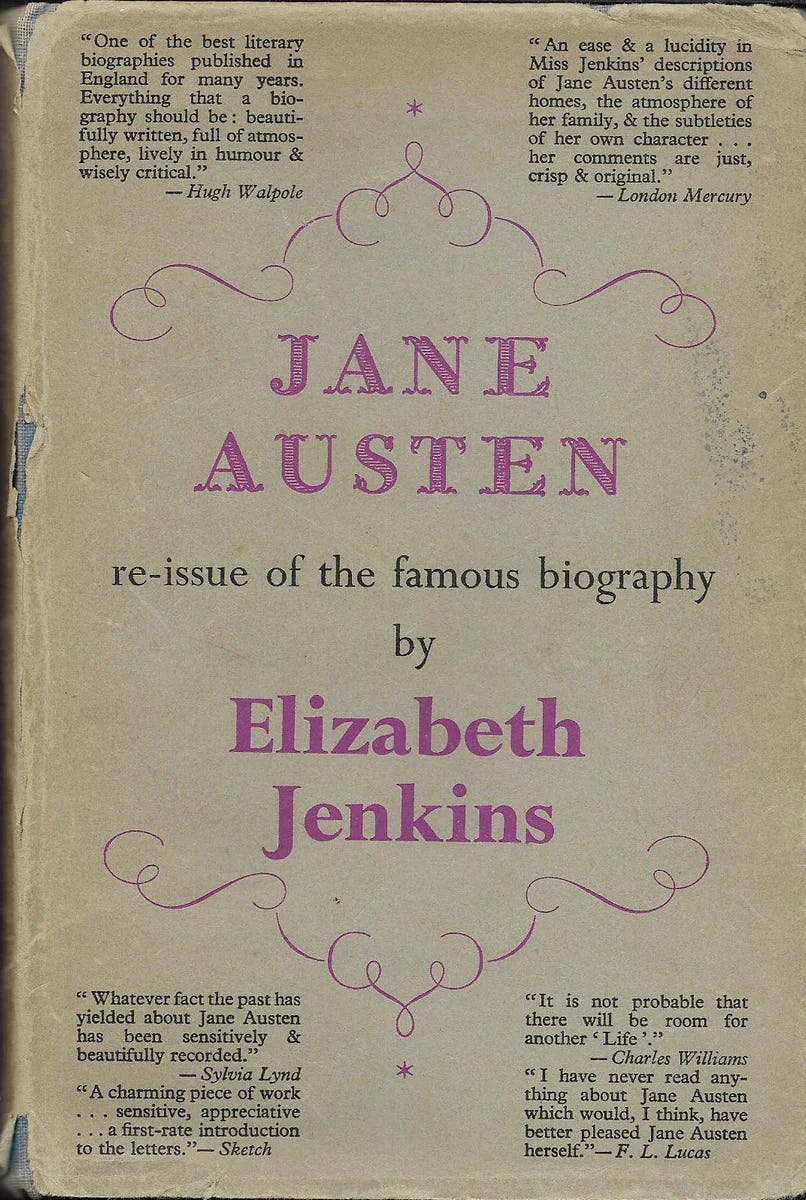

Jenkins’s biography is more than that, though. It is beautifully written, one of Jenkins’ finest achievements. It contains some of the best writing in literary biography of the twentieth century. Little wonder it was so often reprinted. One cover had the subtitle, “the famous biography by Elizabeth Jenkins.” Here is the unforgettable opening.

THE EIGHTEENTH century was an age such as our imagination can barely comprehend; weltering as we do in a slough of habitual ugliness, ranging from the dreary horrors of Victorian sham gothic to the more lively hideousness of modern jerry-building, with advertisements defacing any space that might be left unoffendingly blank, and the tourist scattering his trail of chocolate paper, cigarette ends and film cartons, we catch sight every now and again of a house front, plain and graceful, with a fanlight like the half of a spider’s web and a slip of iron balcony; among the florid or stark disfigurements of a graveyard we discover a tombstone with elegant letters composing, in a single sentence, a well-turned epitaph. Among a bunch of furnishing fabrics, we come upon a traditional eighteenth-century chintz, formal and exquisitely gay; a print shows us the vista of a London street, with two rows of blond, porticoed houses closing in a view of trees and fields. The ghost of that vanished loveliness haunts us in every memorial that survives the age: a house in its park, a teacup, the type and binding of a book.

Jenkins learned her classically elegant prose from reading Addison, from her young admiration for Virginia Woolf—who was so mean, she once made young Jenkins cry—, and from her dearest friend Elizabeth Bowen, as well as from Jane Austen. What makes the book so successful, apart from this, is the deep sympathy between author and subject. Here is Jenkins, writing about Austen’s writing conditions during the production of the late masterpieces:

The many long spells of quiet when the others had walked out, her mother was in the garden and she had the room to herself; or when the domestic party was assembled, sewing and reading, with nothing but the soft stir of utterly familiar sounds and no tones but the low, infrequent ones of beloved, familiar voices—these were the conditions in which she created Mansfield Park, Emma and Persuasion. They seem inadequate, it is true; the important novelists of today, who have their agent and their secretaries, whose establishments are run entirely for their own convenience and who give out that they must never in any circumstances be disturbed while they are at work—these have, in every respect, a superior regime to that of Jane Austen’s unprofessional existence—but their books are not so good.

Jenkins was just such a person. She lived up in Hampstead, with many long spells of quiet, in her Regency Gothic house, furnished as if no time had passed at all. She enjoyed the soft stir of utterly familiar sounds. She was, like Austen, a considerate daughter and a strong Christian. She too was unmarried.

Jenkins had an excellent historical imagination. She was able to put herself in the past, almost too vividly. Such was her sympathy with the period, she lived as if it was still the Regency. Her house in Hampstead was close to the Keats’ House museum, and the two houses were furnished similarly. Jenkins had no mod-cons. When she rented a television to watch the serialization of her novel Dr. Gully, the men who came to take it away after three weeks simply couldn’t believe that she didn’t want to keep it.

As a young woman, Jenkins was a teacher. One pupil said her interest in Austen and her times went so far that ‘She even resembled an eighteenth-century heroine: fragile, inhibited, languishing, yet at times waspish.’ Lindsay Nichols was at King Alfred School from 1928-1935, and his impression of her is vivid, and certainly tallies with everything else we know about her. Here is what he wrote in a school magazine memorial.

She suffered from the cold. In spite of her smallish, centrally-heated room in the new block and ignoring the school’s fresh-air cult of open windows, she huddled in her squirrel fur coat, her bloodless face tinged blue, fondling her mousy curls as she spoke with correct diction and carefully chosen words. An example of her pedantry was the taboo she placed on the word ‘nice’ if used in the sense of ‘agreeable, pretty’, and not in what she claimed was the correct sense of ‘decent, precise, particular.’... She made healthy, athletic tomboys like me feel like barbarians.

I used to be fascinated by the sight of her tottering homewards down North End Road on her high heels, hugging her fur about her and hugging the fence as if suffering from a combination of scoliosis and agoraphobia.

That final image, of a woman suffering from scoliosis and agoraphobia has an echo in something one of her obituaries said about her: ‘She was extremely short (her small, hunched, awkward figure was a familiar sight in Hampstead village); she was shyly unwilling to meet one in the eye; yet she was one of the most understanding and kindly people it is possible to imagine.’

All of these qualities—isolation, historical imagination, neuroticism, kindliness—make Jenkins an ideal Austen biographer.

Austen was a life-long obsession for Jenkins. After she fell down the stairs as an old woman, she spent several weeks in a nursing home. A visiting friend asked if there was anything they could bring her. A set of the novels of Jane Austen was requested. For the weeks of her recovery, Jenkins sat there, reading through the pile of paperbacks, again and again and again. She got to the end of one novel and picked up the next. This came at the end of a lifetime of reading and considering Austen’s works. To Jenkins, Austen was flawless. The only novelist with no deadwood, as she once wrote to the historian A.L. Rowse.

Except for Jane Austen, Jenkins’ best work was done between 1950, when she started writing The Tortoise and the Hare (Carmen Callil told me Tortoise was her favourite of the Virago Modern Classics), and 1972 when she published her own favourite among her books, Dr Gully. She was forty-five when this period started and sixty-seven when it ended.

Jenkins once said of Elizabeth Gaskill, ‘Cranford... appeared in 1852, when Mrs Gaskill in her forty-second year, the prime of a writer’s life.’ Jenkins was herself in her forty-second year when she wrote that; Jane Austen had died aged forty-one.

But her Austen book was her first masterpiece and it still lives on. When I worked in advertising, I mentioned to a colleague that I was working on a dissertation about Jenkins. No-one has ever heard of her. But this person said, “Oh, the lady who wrote the Jane Austen biography?” Her friend had been reading it on the train. You still see it in secondhand bookshops all the time. And once you open it, all its charm is just as strong as it was nearly ninety years ago.

Jane Austen: The Biography has been superseded by others who have the benefit of decades more archival work, and more wide-ranging contextual scholarship. Others have, more dubiously, tried to reclaim Austen in more radical, modern terms. All these books have factual problems. Jenkins is the sort of biographer who speculates about her subject’s feelings. But no-one has yet given us such a well-written immersion in Austen and her work as Jenkins’ did. So much is published about Austen. So little of it will last. As Austen reaches her semiquincentennial, Jenkins’ book is nearly at its century. This year, it was reissued. Of all Jenkins’ work, it has one of the strongest claims to posterity.

I have never been able to bear reading Austin, and don't know if I ever will -- but Jenkin's biography is going on my reading list for sure! And maybe (maybe) after that I'll give P&P another go.

I really appreciate everything you write here, Henry. It always feels like the best kind of learning experience for the way it encourages curiosity about culture and ideas.

Terrific piece, Henry. Enjoyed the T And the H tremendously. Didn’t know about the biography. I always learn from and enjoy your posts.