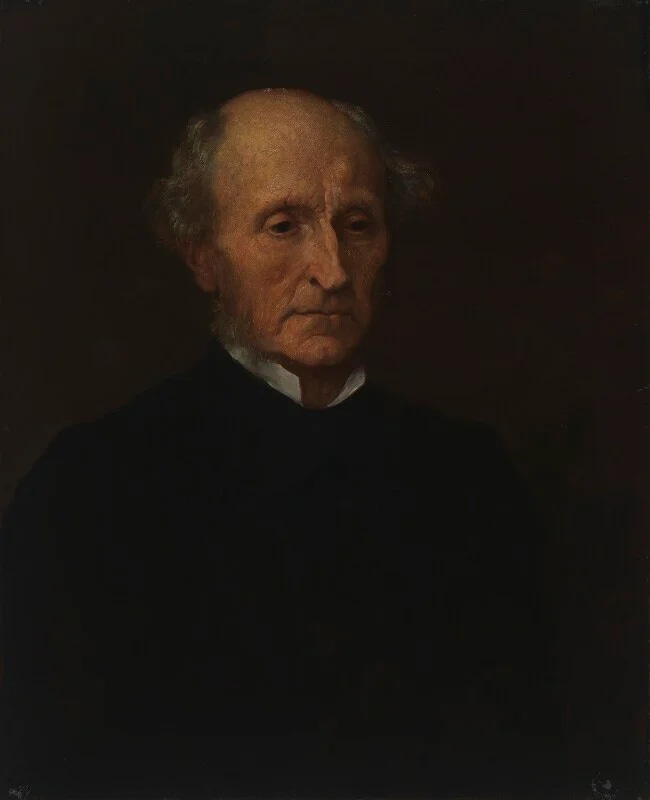

John Stuart Mill’s Autobiography is a Victorian classic. As much as Dickens and Tennyson, Mill represents something archetypal about the Victorian experience. But unlike many other nineteenth century writers, Mill is just as relevant now as he was then. His prose is elegant but elongated, his style is balanced not simplistic, and his register is high rather than accessible: in some ways, he’s very Victorian and not very modern. When some find the lights of beauty, others feel the entanglement of prolixity. But Mill’s concerns are our concerns. Most of all, he is interested in self-development, in what we would call becoming your best self.

To Mill, this is the paramount interest of philosophy and the primary aim of life. Human flourishing is the purpose of politics and the justification for liberty. Far from being a stuffy, unfeeling, hyper-rational utilitarian, Mill is a philosopher whose ideas are grounded insuperably in the spiritual, emotional, and intellectual development of every individual.

This is not just a philosophical ideal: Mill lived like this. Having been homeschooled by his father—reading Greek at 3, Latin at 8, logic, philosophy, and algebra from 12, with an intensive course in economics, and a massive ingestion of history throughout—Mill became one of the most nimble reasoners and expert logicians of his age; for the rest of his life, Mill sought knowledge, from the discoveries of physiology to the recapitulations of ancient history, Mill was always a deep reader and wide explorer of the mind. He taught his sisters, taking one of them so far in maths he told a friend she could have been best in her year at Cambridge had she been allowed to attend. He played the piano, and recited poetry. He studied botany and collected a large herbarium alongside his admirable library. He became the leading expert on French affairs and ideas in his generation. None of this was his main employment.

But, Mill was not always like this. Aged twenty, he had a breakdown, which he called a mental crisis. From his description, it sounds like depression, which cloaked him many times throughout his life.

Mill was raised a Benthamite, meaning he wanted rational reforms to the ancient, distorted, unjust political institutions of aristocratic Britain. Realising that his religious adherence to political reform wasn’t going make him happy was an unforeseen trap. Suddenly, having been raised to philosophical radicalism with the devotion of being raised to the church, Mill lost his faith.

He had nothing to live for. For months he carried on as if nothing had happened, wearing no trappings or suits of woe, but full of depression within. He was flat, empty, numb, dull. It was reading a set of memoirs that brought emotion back to Mill. From there he discovered Wordsworth, and Coleridge, and began to see that analytical habits alone wear down the feelings; a successful life requires both to be maintained. There were, he could see now, deeper springs of human character.

To be happy, these deeper springs required attention. That attention would also make him a better philosopher. Critiquing his former mentor, Mill said that “human nature and human life are wide subjects” and Bentham had “failed in drawing light from other minds.” Mill now became obsessed with many-sidedness, the German idea that we must see all of the world, learn from it all. It was through this many-sidedness that Mill became not just his generation’s pre-eminent logician and economist, but their polemicist for liberalism, their representative for women’s suffrage, and their advocate for democracy. He codified utilitarianism, argued for feminism, and justified liberalism for every subsequent generation.

All of this work came from Mill’s personality as much as from his intellectual ability. His life of constant personal development was the source of his ideas and the generation of his energy. In his archives, among the dozens and dozens of boxes of formal papers, letters, and works, are five botanical notebooks, full of lists of the species he found and identified. The attention he paid to the world was immense. Mill the botanist is part of Mill the libertarian. Mill the pianist is part of Mill the feminist. It takes all sides of life to see life truly, to argue for what life might become.

This is why the Autobiography, published after Mill’s death in 1873, is a bildungsroman, a genre of book associated with novels like Jane Eyre and David Copperfield, where the moral and emotional development of the character forms the substance of the plot, a story in which the protagonist matures and becomes reconciled to society. Mill wasn’t fitting his life to a genre, thus giving an inaccurate picture (though the Autobiography certainly wasn’t the whole story); Mill seriously believed in bildung, that the ideas you believe significantly affect the person you become, and that your life is a continual education, which you ought to take seriously. The compounding effects of what you do add up to determine who you are.

Men more frequently require to be reminded than informed, as Samuel Johnson said, and Mill’s notions of human flourishing and bildung form a lesson we will always benefit from revising.