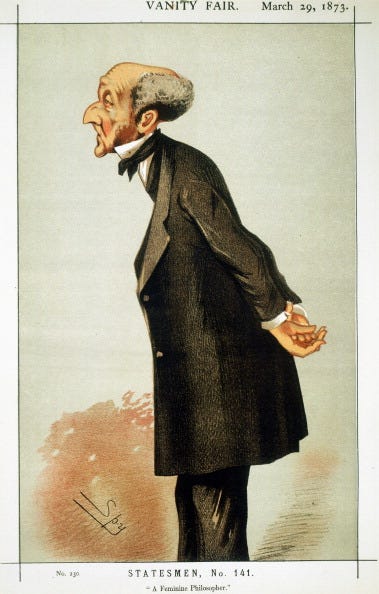

J.S. Mill, hopeless romantic

The prodigal utilitarian came late to happiness

John Stuart Mill was a hopeless old romantic. He is usually thought of as a paragon of rational utilitarian and economic thinking, and he has the stern, crusty face of a heartless Victorian to match this reputation. But his private life was tragic and tumultuous — and without that passionate despair, he would never have written his most enduring work, On Liberty. And, as we will see, it is not entirely his work.

Mill’s childhood was awful. It’s easy to make a case for the defence, but the long and the short of it is that his father used Mill for an experiment that led to him having a breakdown aged twenty. This is sometimes rather charmingly called a mid-life crisis twenty years early. Someone on a Radio 4 programme even chuckled about it. But Mill went through a deep depression with suicidal thoughts. He had no friends he could talk to about his problems. His parents were never loving towards him. And he had lost his entire belief system. He snapped.

For six months he suffered in silence, turning up to work every day where no-one was any the wiser — including his father, who was his direct superior. I’m not persuaded of the benefit of Freudian analysis in biography, but it’s not easy to avoid here.

Mill’s education is often defended on two grounds. First, that it worked. He was half a lifetime ahead of many of his contemporaries, with an astonishing store of knowledge and understanding across ancient languages, philosophy, logic, maths, philosophy and history. Second is that, as Mill himself says, it shows much more can be taught than is commonly supposed. The strongest defence of that second line of argument comes from Helen De Witt in The Last Samurai.

But, with everything we now know about innate ability (Mill’s father believed, following Locke, that children’s minds were blank slates) the system loses at least some of its appeal. Mill had seven siblings, all of whom went through the same gruelling system, and none of them became the founders of a new school of political philosophy. Throw in the fact that errors in young Mill’s work, or that of his siblings who he taught, led to the with-holding of food, and the case for the defence starts to crumble.

The real nail in the coffin is that it fails on its own terms. Mill’s father was a Benthamite Utilitarian who believed in creating the greatest happiness for the greatest number. Mill’s breakdown was a refutation of the experiment in those terms. To be sure, Mill himself would later distinguish between the higher and lower pleasures, and we don’t have to be sentimental about how we define happy. But the end of the experiment was a suicidal depression conducted in solitude and bad lifelong relations with his family. It didn’t make anyone happy.

Mill says of this period, ‘I never wavered in the conviction that happiness is the test of all rules of conduct, and the end of life. but I now thought that this end was to be attained only by not making it the direct end.’ The one pleasure Mill had in his childhood (there were no holidays, in case they encouraged a pattern of idleness), was music. But that didn’t help him know.

He tried reading Byron, but it did nothing for him. What saved him was Wordsworth’s poems of 1815. He found tranquility in this work, because of the relief of contemplating nature. He remained a lover of mountain scenery all his life.

So there he was, a young prodigy who worked for his father and had saved himself from the abyss by reading poetry. He was, at this stage, about as close to the stereotype of an emotionless calculating machine as you could get. Anyone who wanted to discredit the rational ideal would stop the story here.

However, when he was twenty five Mill met Harriet Taylor, a smart woman who was unable to talk about ideas with her own slightly dull husband. Company had been procured for her so she could engage her interest in philosophy with someone suitable. Which is how Mill ended up coming for dinner.

Mill, who had read Greek from the age of three and talked fluently with philosophers from the age of eight, who worked in solitary conditions all day at the East India Company subsisting on a single boiled egg, who would go on to produce seminal and standard works of logic, economics, philosophy, and politics — Mill who was the archetype of a rational, emotionless man — fell head over heels in love that night.

This is what he says about Harriet in his Autobiography:

I very soon felt her to be the most admirable person I had ever known… To her outer circle she was a beauty and a wit, with an air of natural distinction, felt by all who approached her: to the inner, a woman of deep and strong feeling, of penetrating and intuitive intelligence, and of an eminently meditative and poetic nature.

You can tell he’s got it bad. Carlyle could certainly tell, saying

Mill, who up to that time, had never so much as looked at a female creature, not even a cow, in the face, found himself opposite those great dark eyes, that were flashing unutterable things while he was discoursin' the utterable concernin' all sorts o' high topics.

Luckily, Harriet fell straight back in love with him.

The problem was, Harriet was married with children. And Victorian marriage laws were cruel. If she had left her husband, he would have had automatic custody of the little ones. Scandal had to be avoided at all costs, Harriet didn’t hate her husband and Mill had no wish to upset anyone. It was an impossible situation.

'Though we did not feel the ordinances of society binding... We did feel bound that our conduct should be such as in no degree to bring discredit on her husband, nor therefore on herself.'

But Harriet and Mill were a true match. And so that most Victorian of compromises was reached: a sexless ménage à trois. Mill and Harriet would have supper together once a week, while her husband went out to his club. Eventually Harriet and Taylor separated, and Mill visited her more often. There were also visits to Paris, all assumed to be celibate.

Some of this is based on limited evidence. Many letters were destroyed. There are people who find it impossible to believe that when they were in Paris Harriet and Mill were celibate. That is to impose ordinary, modern values onto a pair of unique, Victorian people. But the details are unimportant. The key here is that Mill was, in his own view, deeply unhappy and unloved. (He was pretty vicious about his mother and didn’t even mention her in his Autobiography.) Once he met Harriet he had found his chance for happiness. So the weird, ridiculous arrangement they made was better than nothing.

But it lasted for twenty years.

When they did eventually get married — twenty years after they met, two years after Taylor died, for the sake of decency — Mill’s mother and family were so outraged, and there was such a terrible scene (about a marriage to a widow!) that he more or less cut them out. He was by now a middle aged senior administrator at the East India Company and this was his only chance.

The great proponent of utilitarianism was finally going to be happy.

The newlyweds moved to Blackheath. You can still see their house today. Standing there, imagining all the new houses away, you get a sense of how isolated they would have been. The house was part of a private estate, and there is still a gorgeous street of Georgian and Victorian properties close by. But Mill and Harriet lived in a more isolated spot at the end of the lane. They would have seen the sunset from their upstairs windows and heard the birdsong while they looked over the fields towards Kent.

It was a shelter away from society, where they had been mocked and gossiped about for most of their lives. And it was here that they wrote the two important books On Liberty and The Subjection of Women. Note, they. This was not a case of Mill writing and Harriet editing. There were, Mill assures us, joint enterprises. Every sentence was gone over so often by them both he couldn’t tell who had written what.

Some people doubt this, or call Harriet’s contribution into question. But what reason do we have to doubt what Mill tells us? Part of his earlier breakdown had led him into a form of philosophical Toryism. He eventually came back to a form of Benthamism, but it was in many respects more radical.

'in all that concerned the application of philosophy to the exigencies of human society and progress, I was her pupil, alike in boldness of speculation and cautiousness of practical judgment'

Perhaps unsurprisingly, she was the more feminist of the two of them. She challenged him on topics like that and forced a rethink, often resulting in him moving closer to her radical position. The ONDB entry for Mill says:

When she dissented from his views on such questions as Comtism, Fenianism, atheism, communism, Greek history, and the moral perfectibility of the human race, Mill almost invariably conceded that he was in the wrong and promised to think again: 'by thinking sufficiently I should probably come to think the same—as is almost always the case, I believe always when we think long enough'.

Mill was so unworldly he couldn't summon cabs or reserve seats on trains. Harriet enabled him to live more. It was an astonishing flourishing for both of them, up there on the hill in Blackheath where he played her the piano and they charted a new course for radical liberalism.

But it wasn’t for long. Harriet got consumption. Neither of them was in good health, but she declined fast. They went to France, looking for somewhere to stay where the warm weather would improve her condition. She died in Avignon on the way. They had only been married for seven years.

This story makes me see On Liberty again in different terms. What an intensely personal, romantic book it is. Remember, Mill said, ‘we did not feel the ordinances of society binding.’ And yet their lives with tormented and tortured into an unhappy shape to accommodate social mores and repressive rules. No wonder their joint project was to demonstrate that so long as you are doing no-one any direct physical harm, you ought to be able to do whatever you like.

Far the from the desiccated, selfish, impractical theory it is accused of being, this is in fact a passionate declaration of freedom from two people who were, for too long, kept apart for no good reason at all, other than other people’s gossipy outrage.

Mill lived for another thirteen years after Harriet died. He was an MP for a single term, being mocked for his shrill lecturing tone. Disraeli used to say, when he stood up to talk, ‘here comes the Governess.’ But he was promoting the radical cause of feminism he had developed with Harriet Taylor.

He died in Avignon, in a cottage he had bought that overlooked her grave. There were tall trees in the garden that caused moisture to settle and chill the air, which was bad for his health. He refused to cut them down though, as he liked to hear the nightingales sing.

Autobiography, John Stuart Mill (US link)

Sidetracks, Richard Holmes (US link) — has a good short article on Mill on this topic

J.S. Mill at the ONDB and Wikipedia

Harriet Taylor at the ONDB and Wikipedia and Utilitarianism.net (good article on her contribution)

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

Beautiful