Knights and Hawkes: inside Shakespeare's dream

Shakespeare and his critics. Part I: is character real?

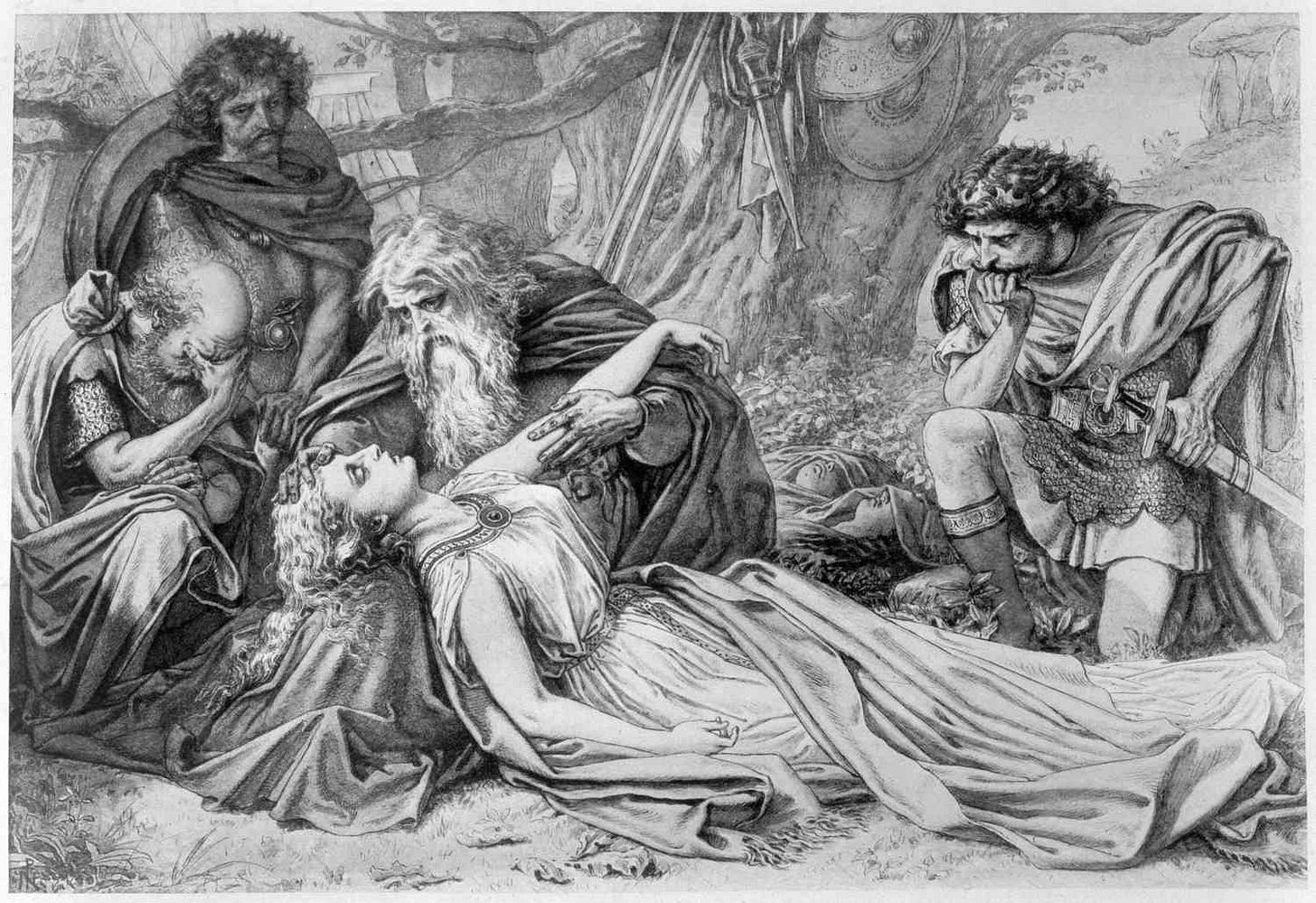

Was Cordelia real?

In May 1994, an undergraduate called Pamela Bunn posted a comment in the online community known as Shaksper, asking about Cordelia’s “character development.” Bunn was wondering how to best convey on stage all the large emotions Cordelia would be feeling in the opening of King Lear. Terence Hawkes, one of the academics who brought the ideas of Derrida, Foucault and other post modernists to Britain, responded like this:

Cordelia is not a real, live flesh and blood human being. In consequence, she has no ‘character’, and it does not ‘develop’. To suppose otherwise, as your teachers have apparently encouraged you to do, is to impose the modes of 19th and 20th century art on that of an earlier period which knew nothing of them. It is, in short, to turn an astonishing and disturbing piece of 17th century dramatic art, whose mode is emblematic, into a third rate Victorian novel, whose mode is realistic. Cordelia has no private motives, or emotions, other than those clearly presented in the play as part of its thematic structure. The play uses her to raise matters of large public concern such as duty, deference, the nature of kingship, the right to speak, the function of silence, the roles available to women in a male-dominated world, and so on. These are not the newly-minted slogans of wild-eyed Cultural Materialist revolutionaries, but the fundamental principles on which informed and entirely respectable analysis of the plays has proceeded for fifty years and more. Read the fine and justly famous essay by L.C.Knights, “How Many Children Had Lady Macbeth?”. It was first published in 1933.

Another way of putting this is to say that the whole play (and only the words of the play) is what matters, not what Knights calls the abstractions of the plot and characters. To talk about Cordelia’s motivations and thoughts is to talk about something not written, and is thus bad criticism. On this view, the characters of the play are not persons, but are “symbols of a poetic vision.”

The historical argument for this perspective is that drama before the age of Shakespeare was largely that of the morality play, in which archetypes were used to make moral points. The most obvious descendant of that sort of drama are the characters in Ben Jonson who represent certain “humours”—these are not individuals, but types, comparable with the work of the Roman playwright Terence. To the contemporary audience, Shakespeare was more like this, part of a culture of sermons and speeches.

Here is how Knights expressed the argument:

A Shakespeare play is a dramatic poem. It used action, gesture, formal grouping and symbols, and it relies upon the general conventions governing Elizabethan plays… its end is to communicate a rich and controlled experience by means of words—words used in a way which, without some training, we are no longer accustomed to respond… To stress in the conventional way character or plot or any of the other abstractions that can be made, is to impoverish the total response.

He then quotes two other critics, first M.C. Bradbrook,

It is in the total situation rather than in the wrigglings of individual emotion that the tragedy lies.

And then G. Wilson Knight,

We should not look for perfect verisimilitude to life, but rather see each play as an expanded metaphor… The persons, ultimately, are not human at all, but purely symbols of a poetic vision.

But impressive as Knights’ essay is (and Hawkes was summarising Knights), what does it amount to? As a commenter on Shaksper said, “We are all deeply indebted to Terence Hawkes for alerting us to the remarkable discovery that fictional characters aren’t real people.”

Seeing the text as a whole doesn’t negate the idea that character matters. The argument is really to declaim a single vision of drama for the period, and then to assume Shakespeare fits that vision rather than alters it.

Indeed, Knights’ basic argument—that we cannot infer anything about a character that is not stated in the text—is flat wrong.

The rest of this essay is for paid subscribers. Below the paywall, you can find out why L.C. Knights was wrong. (But also a little bit right...) And you’ll learn the difference between “opaque” and “transparent” criticism, one of the most useful models for how we talk about literature.

A paid subscription gives you access to essays where you learn the different ways of understanding and interpreting works of literature. If you want to cultivate your taste through deeper knowledge and increased insight, become a paid subscriber today. It’s approximately the cost of a cup of coffee once a week, but gives you access to all my writing. And you can join our book club sessions (usually 7pm, UK time, monthly, on a Sunday; I’m open to other times.)

Knights was wrong…

As A.D. Nuttall pointed out in A New Mimesis, when a character sits up and yawns, we infer they were asleep. When they give a start, in certain situations, we assume they are guilty. (e.g., Macbeth.) Nuttall says that Shakespeare never mentions Hamlet’s legs. Are we not allowed to infer them? Only one of his stockings is mentioned: can we only conclude he had one leg? It sounds silly, but those are the terms Knights set, and Nuttall makes clear that Knights was arguing against a straw-man. No-one actually thinks these characters are real in the way you and I are real. Obviously, some inferences about the off-page lives of characters are absurd; but many are not.

So, Shakespeare’s characters are real. But Knights and Hawkes are also right that play must be seen as a whole. Abstracting the character can often be a way of making vague statements that aren’t supported by the words on the page. The fact that some people are sloppy with their methods of character discussion doesn’t mean character isn’t real; but that’s no excuse to speculate wildly.

Formal criticism vs entering the dream

To help us understand why this critical disagreement exists, let’s look at Nuttall’s distinction between “opaque” and “transparent” criticism. The opaque critics stay outside the art: they are formalist and make the formalities of the text opaque, so we can see how the trick is done, as it were. The transparent critics leave the formal techniques transparent, so that they can be inside the art.

This is an example of opaque criticism: “In the opening of King Lear folk-tale elements proper to narrative are infiltrated by a finer-grained dramatic mode.” This is an example of transparent: “Cordelia cannot bear to have her love for her father made the subject of a partly mercenary game.” To many critics, like Knights and Hawkes, the opaque method is the only real criticism.

Why must we pick sides? Opaque criticism is plainly good criticism. But Nuttall is right:

If the critic never enters the dream he remains ignorant about too much of the work. The final result may be a kind of literary teaching which crushes literary enjoyment… The student who talks excitedly about Becky Sharp will find himself isolated in the seminar. Another student who is careful to speak of ‘the Becky Sharp motif’ tactfully assumes the central role in the discussion.

What the formalists, the Knights and Hawkes, misunderstand is that to isolate and describe formal qualities is insufficient. Art is about life; if Shakespeare is merely using motifs to discuss ideas, why bother with drama?

Many critics think literary character is a flawed idea because real people do not even have a consistent character. But consistent does not mean simple or predictable. The basic philosophical idea that the self is not a single, stable entity is hardly a sound basis for criticism. Shakespeare knew plenty about the instability of human personality.

These critics are distracted into vague theoretical ideas rather than explaining a text. Take, for example, Christy Desmet’s chapter on character in the Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare, about the ways in which you play a part in creating a character when you watch or read the play. Desmet spends remarkably little time discussing Shakespeare or his works. In this extract, Desmet is talking about a data analysis of the language of Shakespeare’s characters.

Craig’s essay records, for instance, the placement of characters based on the frequency of their use of the fifty most common words, the words based on their use by the fifty largest Shakespeare characters, and characters as identified by gender. There could be no more graphic representation of distributed cognition than this, where characters are divided and replicated according to the computer’s superhuman capacity to remember and to process systematically until they become no more than points on a graph. Instead of Bradley’s little world of persons, we have an abstract representation of many persons, figured as data clusters distributed over a geometrically defined space.

It is characteristic of this sort of literary critic not to simply say, “Craig plotted a graph of most commonly used words by Shakespearean characters, which shows. the characters not as real people but data clusters.” More depressingly, it is typical that the graph is not shown, the results and their implications are not really discussed, and the simple fact that such a graph was made is taken as a conclusion in itself.

This is where purely opaque criticism gets you. And it is not very critical. We cannot ignore common sense. Art is mimetic, whatever else it is. Good criticism will be both opaque and transparent.

Shadows of the mind’s theatre.

Shakespeare captured something real about human psychology that wasn’t captured in Jonson. We respond differently to Shakespeare. It feels as if he represents the consciousness of someone else, and as we read him we get something approaching the experience of that consciousness. Now, yes, we must pay close attention, we must listen carefully to the whole play. (Too often we let our pre-existing thoughts and feelings get in the way of understanding literature.) We must read Shakespeare as a poet with a vision.

But Cordelia resembles a conscious person. She is not one, but she is an approximation of one. Her words can be brought to life when acted or read. We don’t feel true grief for her, but we do feel something like grief. King Lear is near unreadable because the ending is so upsetting. That is not because Cordelia is a motif. Character is a lesser form of personhood, but still some sort of form. To ignore this is to ignore something essential about the play. “If the critic never enters the dream he remains ignorant about too much of the work.”

The illusion of character is more than just an illusion. It works on our minds like software on a computer. When I remember the people I have known or are dead, when I think of their words, they are still, in some weak sense, real. If we pay attention to the words, as Knights insists, we will believe in Cordelia: less than we believe in each other, but more than we believe in an emblem. She exists in what Virginia Woolf called the lights and shadows of the mind’s theatre.

As far as I can tell, neither Pamela Bunn nor Terence Hawkes made any further comment on Shaksper about this topic in 1994, though many others had a lot to say, and still do.

This was a great essay! Hawkes seems like kind of a dick! Critics like him privilege every mode of perception besides our own--to them the common reader is the only kind of reader that is always, abjectly wrong. Which is to say, even if Shakespeare didn't mean the text to be interpreted in one way, and his audience was unable to interpret it in that way, surely we, as modern readers, cannot help intuiting some private self inside Shakespeare's characters. Why would our way of perception be any less valid than that of the Elizabethans.

That was absolutely terrific. Why weren't you my English teacher??