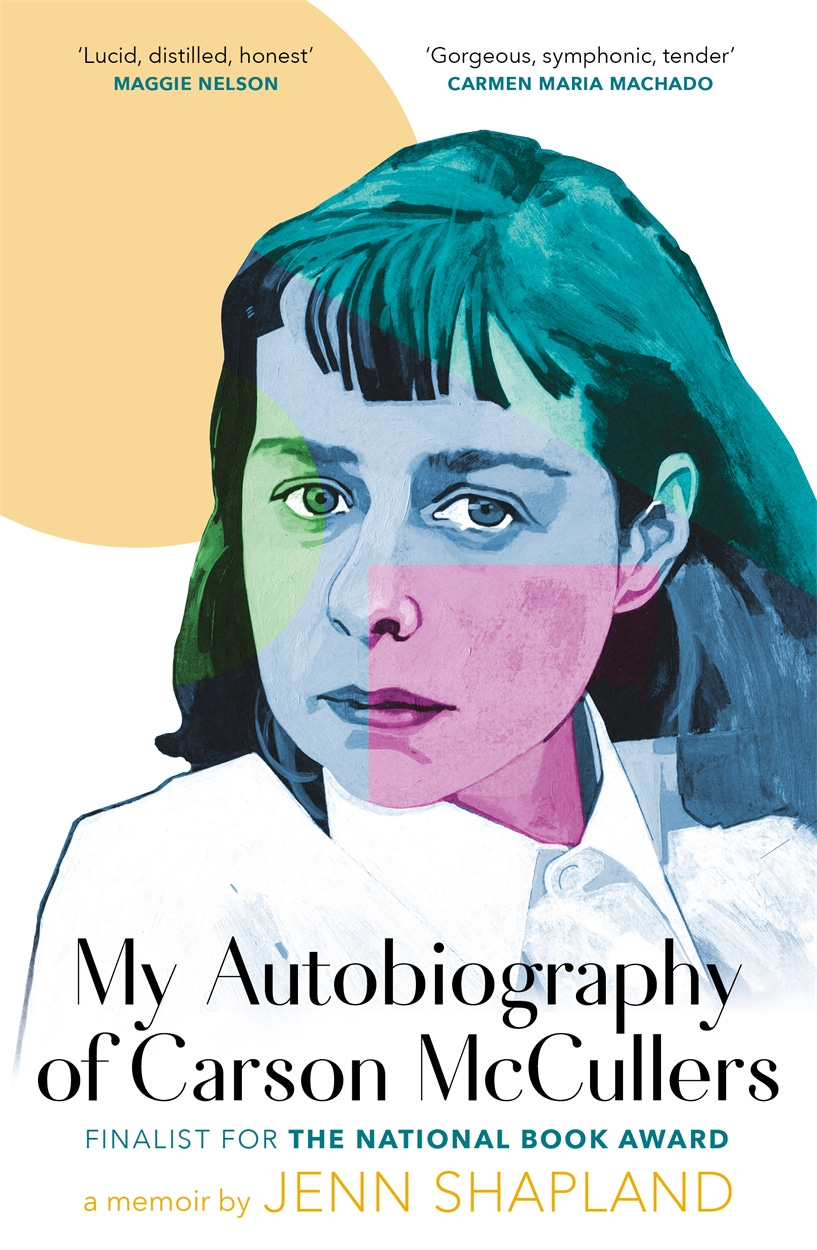

Let absence speak. My Autobiography of Carson McCullers by Jenn Shapland

“To tell her own story, a writer must make herself a character. To tell another person’s story, a writer must make that person some version of herself, must find a way to inhabit her.” This is the premise of Jenn Shapland’s book My Autobiography of Carson McCullers, a title that makes explicit what is tacitly understood in all biographies — the impartial biographer is as much a myth as the impartial novelist.

Let’s put aside the rights and wrongs of this argument, and look first at what it means for technique. By accepting her presence as biographer, Shapland was free to experiment with biography as autobiography. History that attempts objectivity relies on exposition: the straightforward laying out of events. Fiction and drama dislike crude exposition. Shapland uses many small fiction techniques to create a sense of intrigue and bring fictional craft to non-fiction writing.

The second chapter, for example, opens like this. “I wasn’t expecting love letters. The paper was browned with age and wrinkled at the edges. Annemarie’s handwriting filled the page…” That is the first time we have heard about Annemarie. Shapland controls two narratives, the way a novel might alternate between two voices. “I found the letters at the tail end of the major, slow-burning catastrophe of my twenties: never quite breaking up with my first love, a woman from Texas I’d met our freshman year of college in Vermont, after six closeted years together.” She controls and contrasts two story lines, Carson’s life and loves, and her personal life and research journey, to show similarities between them. She writes for action and interest, not prose effect. It is unpretentious. Her chapter endings are often suspenseful. Like this one:

According to Carson, after that first session, Mary invited her to lunch. They talked about books, though Mary had never read any of Carson’s. Their post-session lunches, which continued through April 1958, were for Carson “the solace and high point” of the day. Insisting that theirs was a strictly doctor-patient relationship for the duration of Carson’s therapy, Mary would later deny that these lunches ever took place.

The book is written in an internet idiom. “Like same.” I enjoy this and wish more serious scholarly people were able to write convincingly this way. But Shapland also thinks internet. She knows how to think at the margin. She aims to be “true to life”. She is straightforward. Each chapter could be a blog post. Lydia Davis’ influence is obvious (and well used) but so is the general tone of being alive at the time of the internet. Sally Rooney is rightly praised for being “online” in this sense, and Shapland shares that quality.

Shapland reminds me of Michael Holroyd and Richard Holmes who have written about being consumed by their subjects. (A.N. Wilson once wrote that during his research and writing of Hilaire Belloc’s biography, he would, after a glass of wine, even begin to sound like Belloc.) For Holmes, in Footsteps, the journey to the places his subjects had been was an essential part of his method of understanding them. For Shapland, the same is true; but it goes beyond visiting Carson’s house. Shapland goes through a relatable journey in her identity and the way she presents herself.

I tried to tell a few people—coworkers, friends—about the letters, but I couldn’t explain why they were so significant to me. “She dated a woman,” they’d say. “So?” The years that followed were overtaken by my desire to understand the magnitude of this on-paper love. Within a week of finding the letters, I would chop my hair short. Within a year I would be more or less comfortably calling myself a lesbian for the first time. I would also catalog McCullers’s collection of personal effects at the Ransom Center, her clothes and objects that had made their way into the archive only to sit for years, unprocessed. Four years later I would live in Carson’s childhood home in Columbus for a month, and soon after I would move from Austin to Santa Fe with my new love, Chelsea—we met as interns—abandoning my academic job search to finish a book about Carson. Retrospect redefines everything in its path, and I am as hesitant to ascribe steady narrative meaning to my own life as to any other’s. But I suppose we could call those letters a turning point.

There will be an inevitable resistance to Shapland’s technique — especially as it is applied to queer identity — among people who think history ought to be based on clear and solid facts and not go beyond them. Shapland shares that hesitancy. She spends a great deal of time searching down the paper trail. Persuasively, she also argues that this insistence on a paper trail is often a way of denying queerness. Sometimes this seems like an outright cover-up — Carson’s previous biographers have denied her lesbianism, rather implausibly. This might be deliberate or it might be that because queer lives were inevitably hidden and are therefore fragmentary in the evidence record, they are difficult to establish.

To piece them together, you have to read like a queer person, like someone who knows what it’s like to be closeted, and who knows how to look for reflections of your own experience in even the most unlikely places.

This is an uncontroversial statement when applied to women writing about women. It is a commonplace to say that the largely-male club of historical writers in the twentieth century overlooked and underrated women. It took women biographers to bring those lives to the light. Shapland challenges the standard line historians take about proof when it comes to queer lives.

Historians demand proof from queer love stories that they never require of straight relationships. Unless someone was in the room when the two women had sex (and just what “sex” means between women is, for many historians, up for debate), there’s just no reason to include in the historical record that they were lesbians. At least that’s what it seems like to me.

This is persuasive (and there’s plenty more of it in the book) when it is coupled with the idea that it takes a person of queer identity to properly read the historical record. That is to say, until Carson McCuller’s biography was also, openly and intentionally, Jenn Shapland’s autobiography, McCullers was never understood fully.

I find this so compelling and plausible because I have been researching the life of novelist and biographer Elizabeth Jenkins. One of her great successes was her life of Elizabeth I, which was much praised by the historian A.L. Rowse. Jenkins was the first, but not the last historian, to argue that Elizabeth’s refusal to marry was based on the way the killing of her mother and step-mother scarred her as a child. Jenkins was sexually similar to Elizabeth I in some ways (although I’m not going to give anything away here). It was that personal similarity that enabled her to understand the old queen in a way no-one else had before.

When the record is thin, you need someone with imagination to interpret it.

What is the precise evidence for love? Documentation of sexual encounters? Examples of daily intimacies? Easier to tell and to corroborate are stories of pain, dramatic events, betrayals. Love meanwhile lives in the mundane, the moment-to-moment exchanges, and can so easily become invisible after the people who shared it are no longer alive. But, of course, it leaves traces.

There’s an excellent moment when Shapland says that whenever Carson travelled, Mary came to meet her at the airport, “the contemporary definition of love.”

There’s also a philosophical argument in favour of Shapland’s approach. To insist on finding “smoking gun” evidence of a person’s sexuality in the historical record assumes a theory of the self — that there is a self, that it is constant and conjoined, like a narrative. Other theories of the self see people as more fragmentary than that, more of a bundle of experiences than a single self, more episodic than continuous. This, Shapland:

Now I think of sexuality and identity, gender too, as processes of trial and error. You have to find what works for you. You need a narrative with room for messiness, one that can accommodate veering toward extremes.

There are also many moments of revelatory paper-trail evidence about Carson’s lesbianism, notable from therapy transcripts, which Shapland has not been allowed to quote from directly. There are still people who will not accept the idea that Carson was gay, it seems. Shapland’s beautiful, inventive book is the best rebuttal. By exposing and involving herself so much, Shapland has been more objective than other writers. We can see and assess exactly where and how she has been subjective, and just how carefully she has weighed the material. I started out thinking I would find it hard to agree with her; I am now converted.

The materials, the records themselves, I approach as if they were crime scenes. It’s the archivist in me. I seek to re-create things exactly as they were when I found them, as I found them. I try to show the whole approach, the materials and the gaps and the precise place and state I am in when I’m looking.

This is what historians claim to do. The challenge Shapland has laid down to other biographers is to suggest that it is only by being more involved, acting more like a novelist, that biographers can achieve their ideal. She says, “As with Proust, as with so many queer writers and artists, there is no way to know fully what has been lost or destroyed. It is only possible to let absence speak.” That is precisely what she has done and what so many biographers who do not acknowledge their presence in the work do not do. Shapland’s book shows us that often the evidence is right there in front of us, we just haven’t seen it yet.

I have quoted generously because the best way to persuade someone to read a book is to have them read a sample. If I could, I would simply have posted a series of quotes.

My Autobiography of Carson McCullers by Jen Shapland (US link)

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

Your essay on Mark Landis reminded me of a preacher I knew. He was a late bloomer, entering into ministry in his 40's. He gave powerful, emotional and productive sermons and was a good minister to his congregation. But his sermons were copies of other preachers. He asked for their permission to use them and would add his own anecdotes. He did this because he felt his education was lacking and it affected his confidence. Despite his passion and success as a minister, some in the congregation made it their goal to expose him as a plagiarist. and ruin him as a preacher. In the end, it was clear to me whose actions were most harmful to the people in the congregation.

Thanks for another well-written and thought-provoking article.

First of all, I want to say I agree with your decision to focus on writing. I quit my business job at 41, and I have never regretted the decision. You are exactly "midway in life's journey," so it's a good moment.

I wonder if you might define "late bloomers" more or less in the same way. Artists who only started working seriously (or working at all) after that point. You might consider Ralph Vaughan Williams who didn't become a serious composer until his late thirties. When he studied with Maurice Ravel, he was older than his teacher.

Another obvious great late bloomer is Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, who wrote only one novel, "The Leopard," at the end of his life--mostly spent in diplomatic service. It was published posthumously.

Good luck on your new life. It's not going to be easy but what great project is?