Literature can't save you.

If you want to find meaning, you have to do it yourself.

As anxiety about the future of literature rises, so does faith in its power to heal the self. The idea that literature can save you is once again circulating.

Popular social media accounts like Boze tell us that the decline of reading is why democracy is falling apart. George Eliot is the approved antidote.

James Marriott tells us that “Without the knowledge and without the critical thinking skills instilled by print, many of the citizens of modern democracies find themselves as helpless and as credulous as medieval peasants.”

A new literary podcast series at The Free Press is premised on the idea that “Reading can save” the aimless young men who are adrift in the modern world.

And a piece in this month’s Atlantic about John Cheever quotes him approvingly: “Literature is the salvation of the damned.”

Who am I to disagree? Literature can indeed be a powerful, wonderful, life-changing experience. It can, as Shilo Brooks says in his Free Press piece, “clarify your thinking, cultivate compassion, and provide self-knowledge.”

But—but!—literature can also be none of these things. I admire and support this effort to preach the good word. I only wish we were preaching the whole gospel.

In this age of tweets and podcasts, of the credulous and the drifting, the ancient message of literature being both education and edification has perhaps become a little simplistic…

The great writers and critics have often told us that literature can be useful, ought to be useful. But they have been careful not to promise salvation.

Samuel Johnson was forever saying that most books cannot be finished, that a man “ought to read just as inclination leads him; for what he reads as a task will do him little good.” Books were undoubtedly improving, Johnson thought—just not most of them, to most people, most of the time.

What Johnson knew is that books have no magic. Moral, intellectual, and emotional improvement from books is certainly possible, but, assuming we are reading the best books, we are the key variable. Simply picking up Plato and Shakespeare is not enough.

As the great man wrote in the Rambler on 15th January 1751:

Of the numbers that pass their lives among books, very few read to be made wiser or better, apply any general reproof of vice to themselves, or try their own manners by axioms of justice. They purpose either to consume those hours for which they can find no other amusement, to gain or preserve that respect which learning has always obtained; or to gratify their curiosity with knowledge which, like treasure buried and forgotten, is of no use to others or themselves

Moral improvement is hard. Cultivating the virtues is the work of a lifetime. Agreeing, sentimentally, with Cheever that a page of good prose is invincible (which is to say no more than Horace said about his poets outlasting monuments of bronze), is no guarantee that the prose will do us any good.

So much of what is on offer from this new group of literary boosters is treasure buried and forgotten.

Of course, yes, of course, all reading of the classics is still intrinsically valuable. Buried gold is still gold. But the claim is not that books are merely intrinsically valuable, but that they are instrumentally useful.

Telling someone a book can save them isn’t the same as telling them how it can save them. It isn’t the same as helping them to actually do that work.

Don’t read classic novels to improve yourself morally or to become a better person. Don’t read classic novels to save yourself.

Read them to help you make sense of life, to surprise your imagination with new ways of seeing the world, to get a serious alternative to the culture wars from some of the great thinkers.

Literature has no magic to make moral improvement easier or quicker. It is not going to simply capture the imaginations of a generation of incels and deplorables, nor will the power of a single story solve the emptiness of generational melancholia. These are serious human situations that are not going to be solved with a few novels.

Literature does have that power—only this week, I met someone who had a transformative experience reading Emma—but it is a slow, hard power. Literature works more like the weather than a spell.

In a letter, George Eliot once explained that she was not a teacher, but a companion in the struggle of thought. It is that struggle to which these new preachers ought now to dedicate themselves.

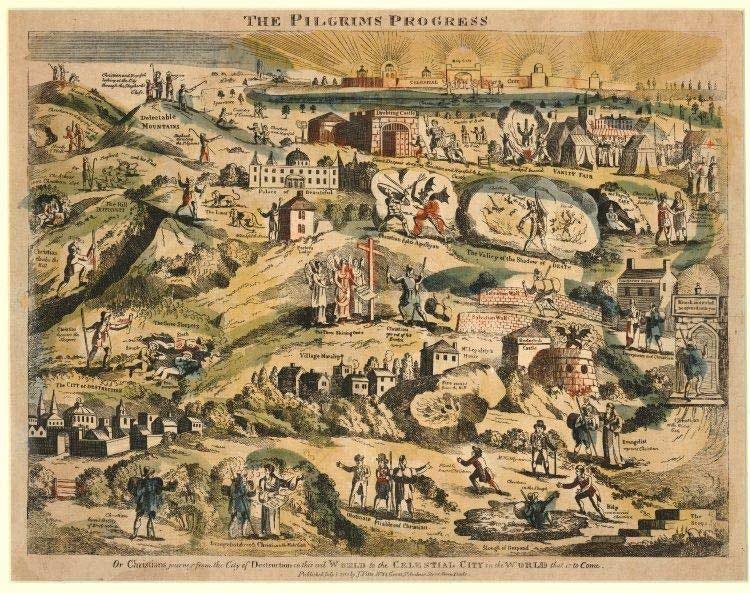

That struggle is why literature has so long been obsessed with the idea of questing. From the Odyssey to King Arthur to Pilgrim’s Progress to Jonathan Swift and Jane Austen and Henry James to Cheever’s Swimmer to Tolkien to Sally Rooney, literature’s primary mode has been the marvellous journey.

Literature cannot save you, but it can accompany you on the quest for meaning.

Quests send us out into the world, send us through trials, send us into the dark lands of wilderness and despair. Quests teach us that we were really seeking virtue, not gold, true love, not a princess. A quest is a cycle to help us see the world and ourselves afresh. It is a long process of moral reformation. All quest is self-discovery, aspiration, virtue riding in the wilderness.

Shakespeare wrote about the journey of the mind. Elizabeth Bishop wrote of the journey to the interior. Those are the journeys on which great authors are our companions in the struggle. It takes a great deal of reading to go on such a quest of the spirit.

Literature is not trying to save you. It is calling to you. The great works of civilisation are trying to show you your life as a quest for meaning.

A lot of people find themselves midway on the path, wandering the wilderness of the world, and they are now turning to literature.

Good. Welcome. Enchantment is the start of change.

Now the journey begins.

What you write about the quest resonates. Literature doesn’t baptize us into wisdom — it walks beside us, sometimes mocking, sometimes consoling. As you say, it’s more weather than spell.

I often think of it bilingually: in French, we say chercher un sens — to seek meaning — and the verb itself implies it may never be found, only pursued. That’s what books do. They keep us walking.

The danger isn’t that people expect too much from literature, but that they stop expecting at all. Better to set out on the road with Cervantes or Bishop, Gide or Johnson — knowing they won’t save us, only remind us to keep going. Or at least to laugh at ourselves when we mistake windmills for giants.

And maybe the real question is more philosophical: what in us can actually be saved? And what are we really hoping will endure?

—

Dave

A very important distinction, it's a step towards understanding but people have to do the hard work of understanding themselves