Martin Amis was overrated

Read his contemporaries instead: Fitzgerald, Bainbridge, Gardam

UPDATE

Some of you disliked the timing of my piece about Martin Amis. One kindly subscriber sent me two very helpful emails, and I see now that it would have been better to wait a few days. My apologies to anyone who was offended.

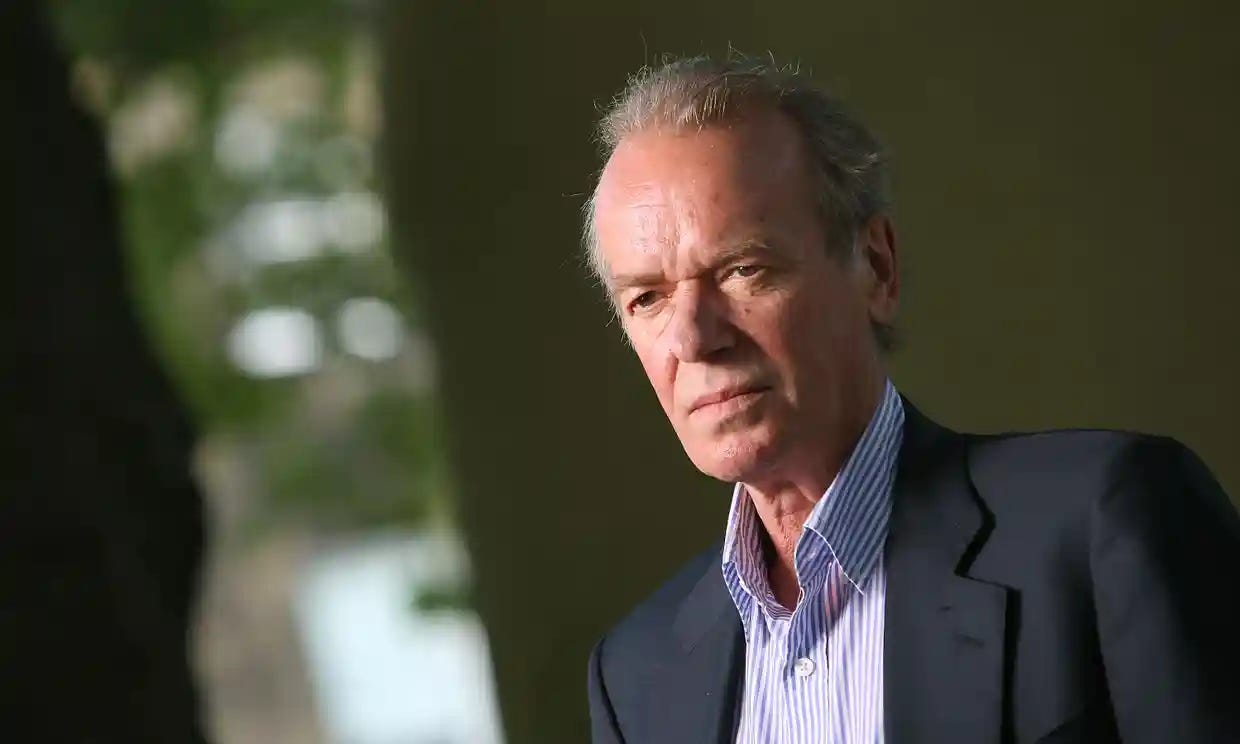

An extra post this week because the novelist Martin Amis has died. We don’t often give hard reviews on The Common Reader but Amis was an unavoidable part of twentieth century literature and as Samuel Johnson said, If we owe regard to the memory of the dead, there is yet more respect to be paid to knowledge, to virtue, and to truth. You’ll find plenty of lionising elsewhere.

Far from being the enfant terrible of English literature, Martin Amis was a conventionally unconventional middle-class novelist who made his name satirising eighties’ greed and then ditched his publisher for a big advance, which he spent on cosmetic dental work. From dreams of being Jonathan Swift to the cold light of sub-Larkinian reality! He said a lot of clever things in clever ways, but that does not a novelist make. He was the beneficiary of a culture that enjoyed making celebrities of clever young men. Without his celebrity appeal, his literary reputation will soon wane.

Let me make a prediction. Amis’ novels, once so shocking to a generation of bourgeois teenagers, will be forgotten as vanity works. His influence will come through his memoir Experience and his book of essays The War Against Cliche, two genuinely brilliant works. Like his friend Christopher Hitchens, he was terribly overrated by the fans and is already being forgotten by the common reader. He was too myopically literary, too distracted by holding poorly informed political opinions, and, frankly, not as good a novelist as his father. Or some of his female contemporaries who were less exciting on television.

People will read Lucky Jim and The Old Devils for as long as there is interest in the comic novel in English. You will not need to read London Fields unless you happen to be especially interested in the 1980s and its discontents. The books of that decade that will continue to hold an audience’s interest were mostly written by women and didn’t grab headlines in the same way. Celebrity and capability were unusually merged during the time when the Booker Prize was televised and we will soon unravel the confusion.

Without his teeth and provocations, Amis will have to rely on his voice and his voice alone—as he said about Money, in a quote you can expect to find in every obituary—and we will find that, like a book of old sermons, we preferred to hear it live. His core mistake was that he spent all his time trying to be James Joyce, saying plots were for thrillers. This from the man who went from delinquent to literary scholar after his step-mother gave him Pride and Prejudice and he went back an hour later saying, “I’ve got to know, does Darcy marry Elizabeth?” No-one feels like that about a Martin Amis novel.

There is only one test of literary merit, which is whether you continue to be read. The first reading of Amis is exciting and intense and wordy. Few go back. Like many novelists who wanted to be intellectuals, Amis was better as a critic. It’s life, he used to say, but is it art? The problem for his works was quite the reverse. It’s art, but is it life? His overlooked contemporaries, Penelope Fitzgerald, Beryl Bainbridge, Jane Gardam, are what will last from that time. That was life. That was art.

There's nothing like Money, or London Fields. And as they are, as you say, books that can have an almost physical effect on you when you first read them, then I think they have a fair chance of enduring.

It's true of course that everything he wrote is to some degree insufferable, and that his public persona was unbearable. In the light of the War Against Cliche, it's rather wonderful that the most memorable sentence written either by him or in connection with his writing is contained in Tibor Fischer's review of Yellow Dog.

It's also true that he wasn't good at some of the things fiction writers should be good at. Though not, I think, because he didn't notice or care about them. I don't think he ignored or downplayed plot, for example; you seem to prefer his writing when he didn't need to construct one (which is reasonable, as his either fell apart, or were so constrictive they ended up boring both him and the reader), but no one could say Money or London Fields were light on plot.

The catalogue of flaws isn't all there is, though. While the essays can be wonderful, and the tips and tricks to beat Space Invaders are useful, it's the eighties novels that are by any measure great. Maybe they would have been less good if the plots had been better. I'm almost sure they would have been less good if he'd known his limitations, and worked within them. There's a crackling electricity to some of his work that I'll never forget. An atmosphere of rancid, seedy masculinity, too; but one transmuted from the leaden awfulness of his father to something else. The other side of the coin to Bainbridge, maybe.

None of the authors who influenced him sound anything like him. There are things he did that I've never seen anyone else do, and that I don't think anyone else could have done. There are experiences he's given me that I couldn't have got from anyone else. Rest in peace.

Henry, thank you for this - an assessment of Martin Amis's fiction I can relate to. I'm a common-as-muck reader who read Money back in the '80s, when the critics were praising it. Unfortunately, the book's merits were lost on me. A workmate of mine - a down-to-earth Londoner - also fell for the hype. She borrowed my copy and, having read it, dropped it on my desk saying, "What a piece of crap." Since then, I've read bits and piece of his other writing and have been similarly unimpressed.

You recommend his essays, so maybe I'll give those a go. I'm put off doing so, though, by some of his views which I've stumbled upon - for example, his dismissal of Raymond Chandler's books as "dated", and Cervantes's Don Quixote as being "unreadable". Well, I'm currently reading Don Quixote and finding it a lot easier to read and enjoy than anything I've read by Martin Amis.