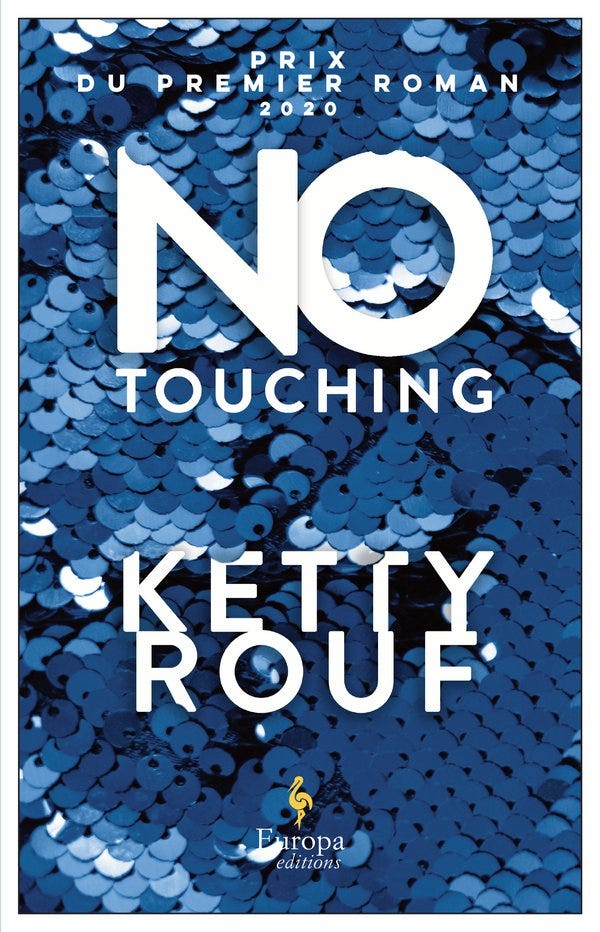

No Touching, Ketty Rouf

It takes the whole of life to learn how to live

To read this book correctly, you must not decide whether to agree or disagree with it but to understand it. It is a combination of the explicit and the restrained that makes optimism out of despair. “At the root of all philosophy is some original disappointment.” In this case, the original disappointment is the bureaucracy of the teaching system. So far, so ordinary. The philosophy developed to deal with this though, is not so expected.

Many people will describe this book as challenging because it is about a philosophy teacher who starts moonlighting as a stripper. The book is not written to make a commentary on the degrading nature of stripping but of teaching, and perhaps the practice of philosophy, certainly of a too-bureaucratic, too-predictable life. The book is pro-stripping as a complement and even perhaps as a substitute for philosophy. “Other than a teacher what can I be with a masters degree in philosophy? A stripper?”

Joséphine is bored to depression. She is crushed by the infantilising mindset of the teaching system. Out of her vapid life she discovers autonomy, self-esteem, and pleasure as a stripper. She trades the escapism of reading erotic fiction on the bus for the empowerment of stripping behind an assumed identity. “Sometimes flowers bloom out of season.”

There are many signals throughout that the philosophical distinction between words and ideas or between things and senses is critical to the practice of stripping. This is a core concept in philosophy, but we do not think about that gap in our own lives. Just as the education system is too bureaucratic to really teach anyone anything, Joséphine’s philosophy is too theoretical to improve her life. She has to do something to shake herself free, not just think.

This isn’t an easy argument to accept when what she does is become a stripper, but that is what makes the book so compelling. No Touching is remarkable and odd because it is a clever thought experiment and a compelling narrative from a premise that isn’t hackneyed or gross but certainly could have been.

Here is Rouf talking about stripping in an interview.

Ideally, strippers are conscious of the fact that they aren’t selling their bodies but rather the spectacle of them. And this is truest in establishments that have the same rules described in the Parisian strip club in the novel. I’m conscious of the fact that practising this profession can lead to all kinds of dangers. But it can also be a means of self-control, of having power over one’s self and over men. I asked a young woman who went from working as a cashier in a supermarket to becoming a stripper what this job did for her and she said: “I learned to say ‘no’ to men and to set my own boundaries for relationships.” In this sense, working as a stripper taught her a greater level of self-respect. Is that the case for all the performers? Maybe not.

Just as we can debate philosophically how real the world is — do we see the chair or do we see an impression of the chair? — Rouf has her character talk about how stripping is an alternative reality, a way of distancing herself from men’s lust, and controlling it. The temptation to argue with the book is immense. Like all good fiction, though, it should be engaged with as a dynamic, not a position. Rouf has created more of a dialogue than a polemic.

“I want to tell you that life is exciting, irresistible, that you have to fling yourself headlong into it, savour it, love it every day…”, Joséphine writes to her pupil, “But I owe it to myself to tell you that it’s sad and repetitive too.”

Whatever you think of the specifics, the idea that action is a more valuable form of philosophy than debate it is underrated. The way Rouf holds different ideas and expresses the balance between them very much characterises the novel. She is clearly capable of being a major novelist and I will be reading whatever else of her work gets translated.

Rouf is a late bloomer, by the way, like her protagonist. As Seneca said, “it takes the whole of life to learn how to live.”

Forgive the catechising Henry but I couldn't resist: this idea that action can be a kind of fulfilment of philosophy is integral to Christianity: this is the incarnation, when "the Word was made flesh" in the person of Christ. Hence the importance of the corporeal, the sacramental (the eucharist, holy water, human sexuality) to Christian life particularly in the Catholic Church. A sharp distinction between mind and body, thought and action, can be characterised as implicitly gnostic theology, and is all too common in today's world, eg the transhumanist idea that our bodies are just meat sacks that can be upgraded or that the human mind is like a disembodied algorithm and is equivalent, ultimately, to an artificially created intelligence. As Belloc said, "all conflict is ultimately theological". Rant over :)

This is expository of "Sex and the 21st Century: AR-W/(P-I) x ATroc = Q" on Amazon Kindle or Paperback. Mostly vol l, "God Made Men Too" now in its 3rd edition, but also vols ll and lll, "The Price Of Eggs is Down" and "Every War Is An UnCivil War" soon to have a new chapter on Putin's War.