Advertising is proclamation. Advertising is the transmission of information. Everyone proclaims. Everyone informs. Come to my party. You’ll love this book. Look! Those cats are fighting! From the ancient messenger to the town crier to the shop sign, advertising was long thought harmless, indeed useful. But now we live in a world of constant salesmanship. Wherever we look, we see adverts. We become inured.

Whoever first thought up the idea of selling the news of battles and sieges so he could advertise powder puffs was, as Samuel Johnson put it, a man of great sagacity. Johnson was an early theorist of advertising, proclaiming that “In an advertisement it is allowed to every man to speak well of himself” and “Promise, large promise, is the soul of an advertisement.” These are still the two main principles of advertising, however much the creatives in modern agencies pretend everything has changed.

So often, modern adverts speak well of a company, but do not make a promise. Boasting with a promise is enticing; boasting alone is dull.

Johnson worried that advertisers “play too wantonly with our passions”—certainly the best advertising is faithful and true. You can put any label on any product, but common sense is capable of discernment. Few are deceived when they see a food truck with WORLD’S BEST CHICKEN written across the top. And yet, there is a whole school of advertising, used in some of the world’s best companies, that does little more than this.

Thus much of what looks like advertising, isn’t. We are inured for good reason.

Unless it contains some useful information, an advert is mere posturing, unlikely to be remembered the instant it has passed by. What makes an advert work, as David Ogilvy said, is the headline and the personality. Effective advertising works like the opening of a good novel. It should leverage a subtle surprise. It works first through mood, then through specifics.

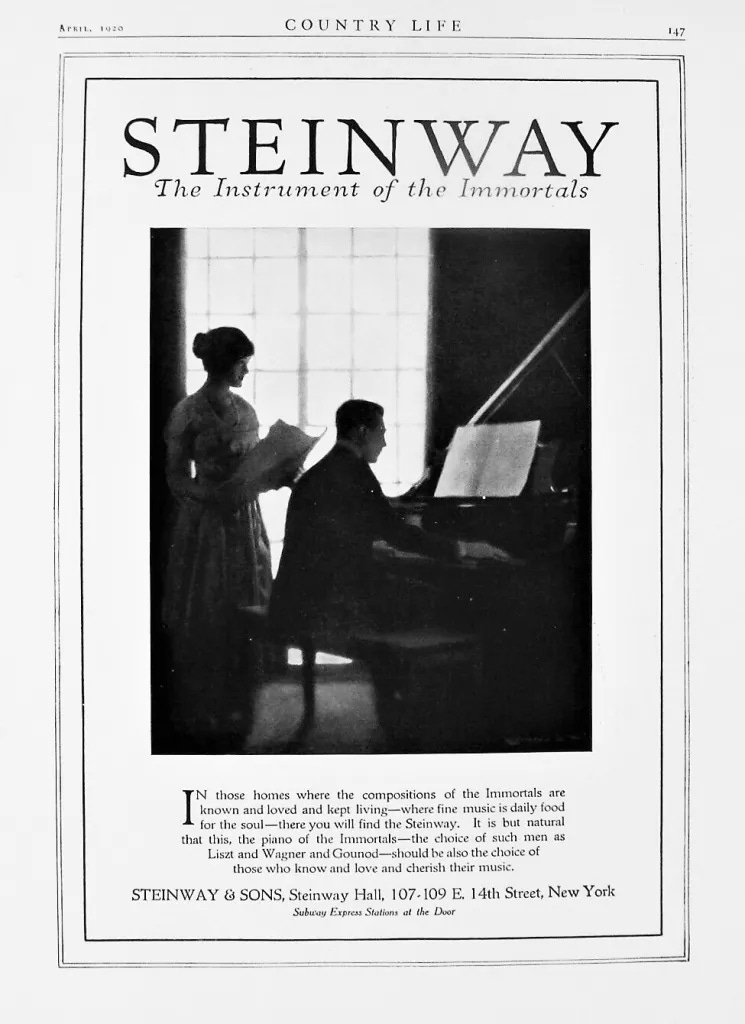

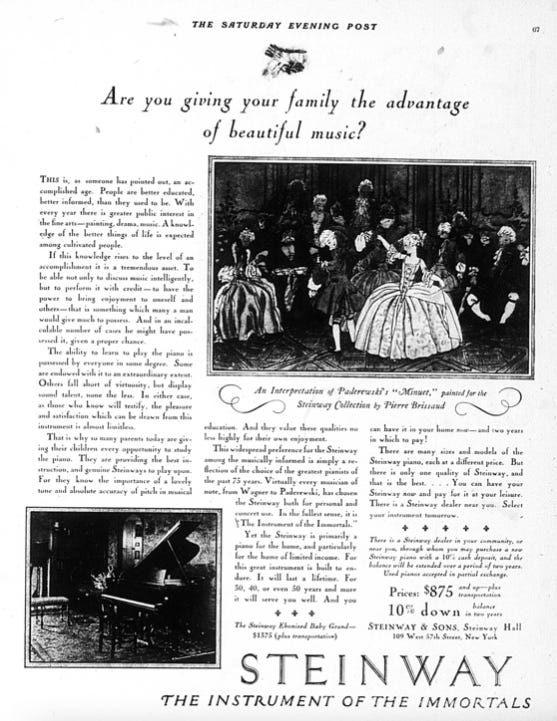

There have been many great copywriters, whose names are sadly unknown to the public now. Many of them deserve greater fame as writers. Raymond Rubicam wrote the great Steinway advert “Instrument of the Immortals” which should still be studied as great copywriting. It is as sharp and focussed as the best internet writing today.

Many advertising professionals think there was a creative revolution the 1960s, which made advertising into an exciting, creative medium which finally broke free of the “rules” which had kept it stale for so long. “Our job is to resist the usual” might have been their motto, only it was said by Rubicam in the 1920s. The creative revolution was a time of new ideas, a new sense of the musicality of advertising, but it was a development of what came before.

The father of modern advertising was not a figure from the 1960s creative revolution. It was David Ogilvy, a titan of the 1950s, who blended Rubicam’s image-based advertising with the research-intense salesman techniques of Claude Hopkins, a copywriter so proficient in his art he made millions writing adverts in the early twentieth century. All good advertising still blends those two traditions today. All brands are images, but the image must be based on a deep understanding of what is being advertised.

In advertising today, predictable, cliched creativity often dominates, but genius is the art of taking pains, as Hopkins said. To break out of the rut of boredom, modern advertising must take more pains.

Dear Henry, April 20 will mark 54 years since I set foot as a copywriter at Leo Burnett Chicago. And I am still going. I would like to add Leo and his idea of inherent drama to your pantheon: find what is interesting about your product and go with it. Best, Ellis