Poor fellow! but a humorist in his way.

George III, Joe Gould, Mr. Dick

In Kew Palace, you can see the empty rooms where various members of George III’s family died, and read short extracts of letters from the princesses who were left behind. It was when Amelia died that George’s second and unending bout of madness began. We do not know what caused George’s illness, but at the end of his life he suffered from some more certain maladies: blindness, dementia, hallucination. He was kept isolated and often conducted long, imaginary conversations. “In short,” wrote one doctor, “he appears to be living in another world and has lost almost all interest in the concerns of this.” He was unable to understand that Queen Charlotte had died. He played the harpsichord loudly, to try and hear something, anything, telling one attendant that the piece he played had been a great favourite of the former king. As John Cannon said, “the last ten years of his life were spent in a twilight world.”

Standing in those rooms, thinking about the cruel way in which George was lost to himself, I thought of Joe Gould and Mr. Dick. There are several Dickensian elements to Joesph Mitchell’s profile Joe Gould’s Secret—the name, Professor Seagull; the physical descriptions of Gould’s filthy condition; the grotesque (literally the comic and the frightful together: that ketchup!); the contrast of simple, honest Joseph with chaotic, ambivalent Joe; the resurgence of romanticism in an age of rational, mechanical progress; the similarity of their names; above all, the fascination with eccentricity and its moral challenges. Who does Joe Gould resemble more than Mr. Dick, Aunt Betsy’s lodger in David Copperfield? Both Mitchell and Dickens were writing semi-autobiographical fiction about an eccentric many would dismiss as mad, or vain, or weird.

And both of them, like poor king George, were lost to themselves.

Many generous readers have become paid subscribers. This helps me to continue writing. Please consider supporting the Common Reader today. Subscribers become members of the Common Reader Book Club (details at the bottom). There are also occasional subscribers’ only posts. If you want to support the Common Reader and join the Book Club, subscribe today.

Like David Copperfield, Joseph Mitchell is unsure if he will be the hero of his own story. His prose has the plain, injunctive style of hardboiled detective fiction made affable and polite—he is a diffident Philip Marlowe in a rain mac. Both he and Gould are unlikely heroes, each other’s mirror, as Copperfield was for Dickens. However intentional, this mirroring is fundamental to Joe Gould’s Secret. Joseph is respectable, employed, conventional; Joe is not. Joseph is reasonable, patient, workmanlike; Joe is erratic, unreliable, volatile, a postulant with no interest in obedience. Both are writers. Both ambitious to catch the fleet ephemera of New York, which they crawl around like entomologists and insects. Joe is Joseph’s shadow; Joseph shadows Joe. When Mitchell reveals that Gould’s proclaimed Oral History of the World was fake, he reveals, slyly, that his profile, too, was a ghost hunt without a ghost. Gould never did anymore than re-write a few familiar stories about his life again and again. Mitchell’s profile is an expansion of an earlier piece of work about Gould. Both of them, in the end, find obscurity: Gould died and Mitchell never wrote again.

What links them was a difficult obsession with a subject that was never quite real. And so we come to Mr. Dick.

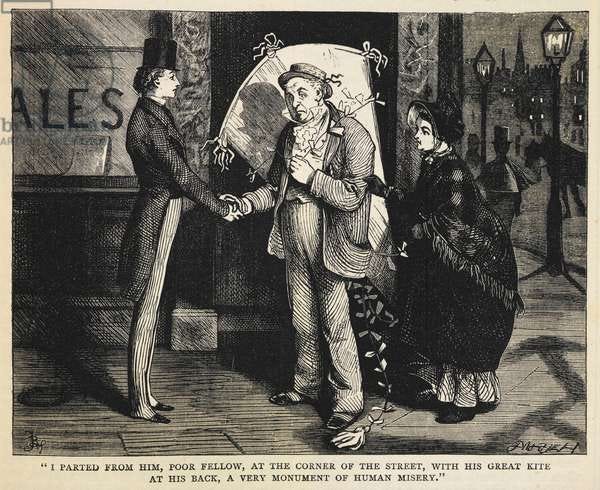

Betsy Trotwood is a stock character whose immediate antecedence is from the comic monsters of Jane Austen: this type later evolved into the loveable but fearsome aunts of P.G. Wodehouse. Betsy overcomes the cliche of an old dragon. She is everything you expect: stern, formidable, fastidious, especially about not letting donkeys walk on her lawn. But she is soppy-stern. Her soft-spot is for Mr. Dick, a man whose relatives tried to lock-up in a madhouse. Mr. Dick is the confused, adorable, idiosyncratic shadow to Betsy Trotwood’s respectable asperity, the Joe Gould to her Joseph Mitchell. Rather than obsessively re-write a selection of stories about his life and lie about an oral history of the world, Mr. Dick is unable to produce his autobiography because he is stuck on an obsession about the head of King Charles I.

You might think the obvious difference between Mr. Dick and Joe Gould is that Joe was real, Mr. Dick fictional. Here the business becomes complicated.

Gould’s Oral History resembles Mitchell’s reporting. Mitchell went out into all the corners and crannies of New York and reported vividly the people he met, presenting their speech, manners, appearance, mannerisms with unusual perspicacity and clarity. Like Gould, he collected the real talk of ordinary people. Mr. Dick’s attempt to write the narrative of his maltreatment at the hands of his relatives resembles Dickens’ own abandoned attempt at autobiography, which he fictionalised in Copperfield.

Mitchell is an exceptional writer of the plain style, though like many twentieth century writers his relentless literalism can fray your attention. Despite his adherence to plain fact, he strays from the truth: he crosses the line, but never tells us when, exactly, or how. His use of the fertile fact was all too good to be true: like Gould, or Mr. Dick, his obsessions became imaginative fancies as well as factual reports. He knew that sometimes, there is no line: the way you imagine something to be is the way it continues to exist. What makes you real is not the extent to which you can be verified but your psychological continuity, the ongoing stream of thoughts, feelings, emotions, and memories . Mitchell makes Gould real today, in our reading of his work, as Dickens does with Mr. Dick, and the question of pure, literal truth is less important than that. Like David Copperfield, Joe Gould’s Secret is a true fabrication of the author’s life.

There comes a point when all of us are lost to each other, whether we are oblivious to the world like George III, eccentric to the point of delusion like Mr. Dick, or just another Joe Gould or Joseph Mitchell, not quite sure when the real experience ended and our slightly imagined memory of it began. As Northrop Frye said of another mad king:

Perhaps Lear’s madness is what our sanity would be if it weren’t under such heavy sedation all the time, if our sense or nerves or whatever didn’t keep filtering out experiences or emotions that would threaten our stability.

Here is Joe Gould, making the same point about the difficulty of distinguishing the mad from the sane, the real from the delusion—

I would judge the sanest man to be him who most firmly realizes the tragic isolation of humanity and pursues his essential purposes calmly. I suppose I feel about it in this way because I have a delusion of grandeur. I believe myself to be Joe Gould.

The next book club is 14th May 19.00 UK time where we will be discussing David Copperfield and thinking about the intersection of fiction and autobiography.