Fiction and theory of mind

Asked how to know if an AI has a ‘theory of mind’ (i.e. whether it can really understand that another person has consciousness, or if it merely pretends to), the psychologist Paul Bloom (whose Substack I enjoy), recently said,

…here’s a good test. Read it half of a good novel and then ask what’s going on here. What’s going to happen next? Show it half of a TV episode. When we do these things, our theory of mind is just fully operational.

People are good, Bloom said, at knowing that the detective takes revenge, the scorned woman leaves, etc etc. (In response, Tyler Cowen said he might not pass such a test as he usually comes up with endings that are less likely to happen (though more interesting)).

This raises a couple of interesting literary questions. First: why do we enjoy fiction in which we can predict the ending? I call this the “expectation of astonishment.”

Just because we can figure out the sort of thing Walter is up to, doesn’t make it less shocking. If I could predict the future (in a credible way) and told you someone would fall off a building, you would still be horrified when you saw it happen.

Indeed, perhaps more so. The “surely it can’t be going to happen” factor only makes a death more dramatic. Hitchcock understood this.

This leads to the other question. How predictable is good fiction? (Or how high is entropy in good fiction?) One of the things that makes Shakespeare so compelling is that, in many of his plays, there is enough dramatic possibility for the ending not to meet our expectations. I once wrote out six possible endings for The Winter’s Tale, a play which has such a strong plot hinge in Act III, we can envisage events turning out quite differently.

To think abut this question, let’s look at some ways in which The Truman Show could have turned out differently. What’s interesting about this example is that there’s an audience in the movie, so we can think about the ways Truman might have been different, but also see what we think of the in-movie audience’s own theory of mind.

A quick plot summary.

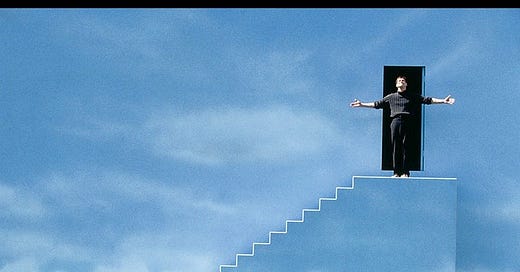

Truman is the star of a reality TV show. He has been on the air 24 hours day for his whole life. One day, a camera falls out of the sky. Truman starts seeing unusal things. Trapped in an unhappy marriage, he yearns for Sylvia, a former actor on the show. They fell in love, and she tried to tell him the truth, but the studio made sure she quickly disappeared. As Truman begins to catch on to what is happening, the cast manipulates him into staying. (The director, Christof, even contrived to fake the death of Truman’s father in a sailing accident when the boy was little so that Truman would be terrified of water for his whole life and thus never leave the island he lives on.) In the end, though, after trying and failing to escape, Truman sneaks out at night and sails away, reaching the “end of the world” and stepping off set. Sylvia, who has been watching, runs to meet him. The last thing that happens before he leaves is that Christof talks to him, like the voice of God from the clouds.

It seems like an inevitably ending, especially relevant to our world. So, how might this have gone differently?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Common Reader to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.