Housekeeping

My wife is setting up a pen pal network for children. You don’t have to be homeschooled to join. She’s already connected several families. My children have exchanged letters with a family in New Zealand. Sign up here.

It’s been a long time since I wrote about Samuel Johnson. New readers can find previous essays about Johnson—as a late bloomer, a potential revolutionary, a mystery masochist, and more—in the archive.

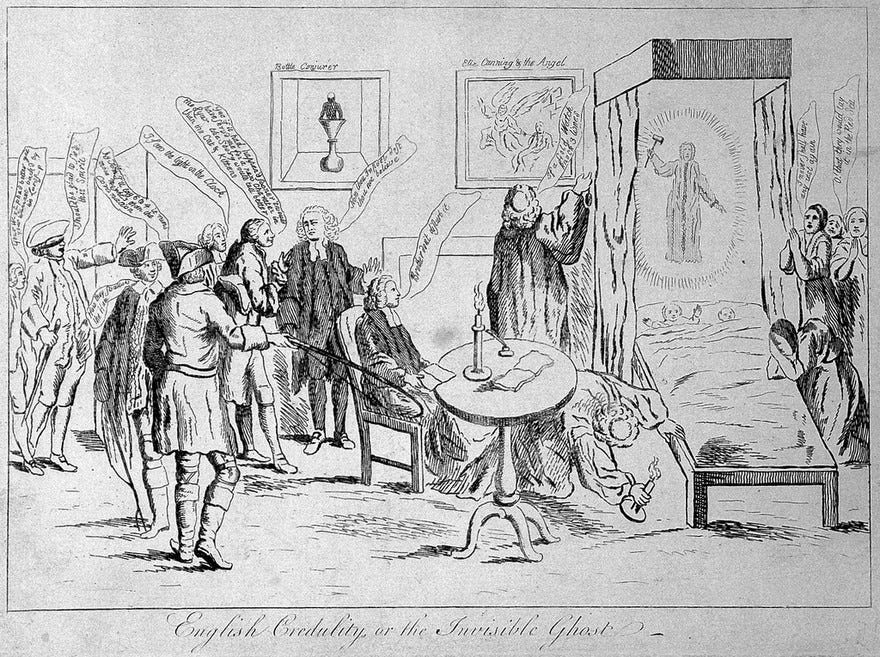

A scandal in Cock Lane

Samuel Johnson is often characterised as a dogmatic thinker. He was a firm Anglican who disapproved of religious dissent. His deeply-held, old-fashioned Toryism made him hate all Whigs. Admiration for his criticism is often qualified by nervousness about his right-wing politics and his prejudices. But there are many instances where Johnson’s judgement put aside his beliefs, such as when he included the hymns of Issac Watts in the Lives of the Poets series, even though Watts was a dissenter, not an Anglican.

The story of the Cock Lane ghost shows this side of Johnson at its best. He kept a rational head when all about him were losing theirs.

The episode began after two advertisements appeared in the Public Ledger. The first told of a young lady who was lured to London, imprisoned, and then poisoned. The second told of her ghost, which was haunting a house in Cock Lane. The ghost was Fanny Lynes and the man supposed to have poisoned her was William Kent. It wasn’t just a ghost story but a good old fashioned tabloid scandal. The whole town was divided.

What makes this story so interesting today is that we still disagree about these topics—not just ghosts, but UFOs. We still see people make wild judgements about scandalous stories based on their prior beliefs. So much about the ghost of Cock Lane seems very typical of the eighteenth century. But so much of it feels so familiar. Whatever our prior moral beliefs were about the people involved in a story tend to determine our opinion. Not Johnson, though.

And yes, before you ask, Cock Lane is named, quite literally, after the sort of business conducted there in mediaeval times as many London streets were. This system meant you knew where to go to get what you wanted. Just as Bread Street had housed bakers, and Milk Lane had dairies, Cock Lane once hosted brothels.

We are more interested in the ghost that may or may not have lived there once in 1762. Let’s begin with the backstory.

William and Fanny

William Kent had previously been married to Fanny’s sister, Elizabeth, who died in childbirth. Fanny was living with them, and stayed to take care of the baby. At this time, they lived in Norfolk. Soon, William and Fanny wanted to get married. He went to London for legal advice. Because Elizabeth had given birth to a living child, the marriage would be considered incestuous. So William moved to London permanently, leaving Fanny in Norfolk.

But she wrote to him, told him she wanted to spend their lives together, and soon joined him in Greenwich, where they lived as if they were married and made wills in each other’s favour. Fanny’s family disapproved. Word spread. They moved. Their new landlord refused to repay William a £20 loan, probably because he found out they were unmarried. William had him arrested for debt. But they had to move again.

At a church service in St-Sepulchre-without-Newgate, they met Richard Parsons, who offered to let them rent a room from him in Cock Lane. William also leant money to Parsons.

Now the tapping began. Fanny heard the noises in bed. The landlady told her it was a neighbouring cobbler. Then she heard the tapping on a Sunday, when the cobbler wasn’t there. The local pub landlord claimed to see a ghost on the stairs, as did Parsons. Kent was away for all of this. Fanny was with Parsons’ daughter Elizabeth when she heard the sounds.

William and Fanny tried to find somewhere suitable to live, but she got smallpox and died before she gave birth. That was 1760. The following year, Kent sued Parsons for three guineas that Parsons owed him.

Then in January 1762 the knocking started again. And the public scandal began.

Seancés and suspicion

Parsons and a man called John Moore, a rector at another church, asked the ghost questions—one tap for yes, two for no. They learned that the ghost was Fanny, come back to accuse William Kent of poisoning her with arsenic. The first ghost, they surmised, must have been Kent’s first wife, warning Fanny she was about to die. Now Fanny had come back to seek justice.

Suspicion lighted on Kent partly because he had screwed down the lid of Fanny’s coffin, which meant her sister had not been able to see the body. Her family was upset that she had left William Kent all her money, a further sign of suspicion, even though it was a small amount and Kent was well-off. And of course he and Fanny were unmarried. The ghost was a reminder of his sin.

A series of seancés had been held in early January 1762 as Kent tried to clear his name. The doctors who saw Fanny before she died were taken there, and her former maid. When Parsons’ daughter Elizabeth went to stay in another house for a day or two, the ghost followed her. Interest started to build in the girl. Elizabeth was moved again and a seancé held, this time much less conclusive. The girl showed signs of nervousness and claimed to have seen the ghost.

This was mid-January 1762. The news was spreading through London. Nobility took an interest. Cock Lane is a small street near the City border, behind St. Sepulchre-without-Newgate. At this stage, the street was often impassable because of the crowds gathering to look at the house where the ghost was heard. Parsons took advantage and sold tickets.

Obviously, the whole thing was a hoax, done to damage Kent’s reputation, perpetrated by Richard Parsons, who was cross about the debt. But this is only obvious to us. It took the visitation of a committee to Cock Lane to discover the fraud. Among that group was Samuel Johnson.

The mystery revealed

His first biographer John Hawkins thought it abased Johnson’s character to be so interested in this story. Others had mocked Johnson’s suspicious credulity. In his biography, Boswell swiped back. Johnson had been “ignorantly misrepresented as weakly credulous” on the subject of ghosts. Instead, Johnson had “a rational respect for testimony”. He was willing to submit to something “authentically proved”, even if he couldn’t understand it. It will surprise readers, Boswell says, to learn that Johnson was one of the people who detected the imposture and undeceived the world. Others assumed they knew the answer: Johnson went to see for himself.

After the committee visited Cock Lane, Johnson wrote an article about their findings:

…they were summoned into the girl’s chamber by some ladies who were near her bed, and who had heard knocks and scratches. When the gentlemen entered, the girl declared that she felt the spirit like a mouse upon her back, and was required to hold her hands out of bed. From that time, though the spirit was very solemnly required to manifest its existence by appearance, by impression on the hand or body of any present, by scratches, knocks, or any other agency, no evidence of any preter-natural power was exhibited.

Obviously, the girl, Elizabeth Parsons, was making the noises. Two more tests were set up, away from Parsons’ house. Every time Elizabeth was told to put her hands out of bed, the noises stopped. A maid saw the girl conceal pieces of wood in her sleeves. She was making the noises under duress from her father. He was soon sent to prison.

People believe what they want to believe

With hindsight, the whole affair seems so silly. A small girl was clacking bits of wood together. On 9th July, the Derby Mercury reported Parson’s trial: “Many ridiculous circumstances which occurred in the several conferences with the pretended Ghost, as related by the Evidences, afforded much Merriment to the very numerous Audience.”

It was easy to laugh six months after the event. At the time, it wasn’t so obvious. The hoax worked, to begin with, because everyone involved had some prior beliefs that shaped their opinion. Many people were prone to believe in spirits. It was common to see the ghost warning about the sinfulness of two people living together unmarried.

In his account of the affair The Mystery Revealed, Oliver Goldsmith wrote, “It is somewhat remarkable, that the Reformation, which in other countries banished superstition, in England seemed to encrease the credulity of the vulgar.” Many Anglicans took this view, that belief in ghosts was Catholic superstition. The new Methodists were more inclined to believe in ghosts. Thus opinion divided.

Johnson was a good Anglican. And he wouldn’t have approved of living in sin. But attached though he was to the doctrines of the Anglican church, he knew the ghost needed investigating.

He told Boswell that if he heard a voice tell him he was wicked and ought to repent, “my own unworthiness is so deeply impressed upon my mind, that… therefore I should not believe.” He knew he was more likely to deceive himself though “the mere strength of his imagination” on subjects he had prior beliefs about. He would believe in ghosts if one told him something factual that he had no means of knowing and could then corroborate.

He wanted the afterlife to be real, but he wasn’t going to let that determine his beliefs. As Johnson said

It is wonderful that five thousand years have now elapsed since the creation of the world, and still it is undecided whether or not there has ever been an instance of the spirit of any person appearing after death. All argument is against it; but all belief is for it.

He was one of the few rational people involved in the ghost of Cock Lane.

Re Johnson's criticism, often linked, as you mentioned, to his politics and prejudices. Most often menioned in his criticism of Milton's "Lycidas," which, like much, is simply misunderstood by later critics because they did not read it in context. It begins with what the poem is NOT, which should have been a clue to some outside source to which he was responding. Johnson wrote for his time. And in his time the Wartons and others of the Whiggish, romantic sort were elevating that great poem over the greater epic, "Paradise Lost." They were using it as a touchstone for what poetry should be. It is against the backdrop of their writings and editions of Milton's work that his infamous criticsm of "Lycidas" must be read to be understood. The older I get, the savvier I realize Sam'l Johnson was.

This is an excellent example of what I consider genuine skepticism: an openness to the unbelievable and mysterious, while simultaneously demanding evidence and reason.