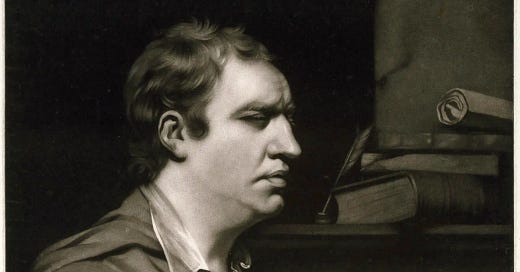

Yesterday was Samuel Johnson’s birthday. To celebrate, here is an essay I wrote in 2020—before most of you were reading The Common Reader—about Johnson as a late bloomer.

Unlike a lot of self-made people, Samuel Johnson was lazy. He got up late and often stayed in bed until the afternoon. He never held down a real job. He thought the two best pleasures were ‘fucking and drinking’, which left him confused as to why more people weren’t drunk more often because they certainly weren’t fucking enough. He had a terrible caffeine addiction and often drank tea late into the night, getting through pints of it every day.

And yet, he was prodigious. As well as the famous dictionary he wrote poetry, biography, innumerable essays and reviews, a philosophical novella, a travel book, he edited Shakespeare, and produced the monumental Lives of the Poets. He was no slouch when it came to research. He once told George III that in order to write one book you ‘have to turn over half a library.’

This dual personality is a mark of his depression. Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy was his favourite book, the only one that got him out of bed earlier than he wanted to get up. He loved his wife but suffered from sexual loneliness and dissatisfaction. He was a widower for a long time and was often moody, prejudiced, argumentative, and solitary.

But he was also warm hearted and generous. He found Oliver Goldsmith on the verge of being homeless and used his critical influence to sell The Vicar of Wakefield that afternoon to save Goldsmith from penury. He left money to his servant, Francis Barber, a freed slave whom he treated as an equal and wrote encouraging letters to help his education, telling him ‘you can never be wise unless you learn to love reading.’ He maintained a circle of close, committed friends.

He was deeply religious. He found spiritual things moving and important from a young age. The ghost in Hamlet scared him so much as a ten year old that he didn't read the play again for years and years. He was a stubborn High Church Tory in the age of Whiggery. He was also a borderline Jacobite.

Before he was famous, he was a failure. For his whole life, he resented the poverty he had lived in when he was young in London. He’d had to save his one clean shirt for the day in the week when he made house visits. He left Oxford because he couldn’t afford the fees. He founded and ran a failed school, losing most of his wife's money in the process. After that his play Irene, written to be the great tragedy of the age, was a flop. Aged 30, he wasn’t shaping up to much. It was about then that he took to hanging out with the reprobate Richard Savage, drinking and roaming the streets of London all night. At this time he was in his early thirties, living away from his wife.

His poetry was powerful: Harold Bloom thought he could have been Pope’s successor. When Irene failed he wrote London, which is still anthologised. But his real genius was not poetry, but judgement and compression. In his mid-thirties he wrote a biography of Savage which is a masterpiece.

The decade from the mid 1740s to the mid 1750s were when he produced the Dictionary, The Rambler, and The Vanity of Human Wishes. Three canonical works, each in a different mode: reference, journalism, poetry. At the end of that decade he was arrested for debt. He then worked on his edition of Shakespeare, The Idler, and Rasselas, which he wrote ‘in the nights of a week’ to pay for his mother’s funeral. It was an extraordinary fifteen years.

And all of this was done without a degree. He was a prodigious reader, alternating his bouts of depression with astonishing industry. Early in the 1760s he was given a government pension, but he still produced Lives of the Poets. It’s an astonishing record for a man who didn't even have a degree.

His sharp lapidary judgements would have thrived on Twitter and his essays would have been ideal blogs. He finds Milton’s early poetry dissatisfactory, and Paradise Lost is described as a great poem that ‘no one ever wished longer’. He was a non elitist, praising the common reader above the professional academic, perhaps unsurprising after Oxford’s snobbish credentialism. He thought interest was the main criteria for assessing a book and gladly threw books aside that lost their appeal.

He is mostly remembered because of Boswell’s biography, which details all sorts of weird and wonderful things about him, like the fact that he always kept his orange peel to put in his shoes, or his strange behaviour, twitching and rolling around and muttering, like he had tourettes. People who met him found his intelligence literally unbelievable after they had observed his ‘strange antic gestures’. He also had terrible eyesight and read with the book very close to his face, so close to the candle he scorched his wig. His friend Thrale worried he would set himself on fire.

But he ought to be remembered for his writing and his strong minded independence. He was an autodidact, and a powerful example of the Fitzgerald Rule. Who would have seen the potential in that strange man wandering the streets with Richard Savage, a well known liar and fraud? Only the people who could recognise that he was an opsimath: a lifelong learner and a late bloomer.

He is the source of this blog’s title:

I rejoice to concur with the common reader; for by the common sense of readers uncorrupted with literary prejudices, after all the refinements of subtilty and the dogmatism of learning, must be finally decided all claim to poetical honours.

You can really see where Harold Bloom got it from.

Where else can you find sentences like this in footnotes to Shakespeare?

When we are young we busy ourselves in forming schemes for succeeding time, and miss the gratifications that are before us; when we are old we amuse the languour of age with the recollection of youthful pleasures or performances; so that our life, of which no part is filled with the business of the present time, resembles our dreams after dinner, when the events of the morning are mingled with the designs of the evening.

If you haven’t read him, try Johnson on Shakespeare (bookfinder link), one of my favourite books, or dip in and out of his Rambler and Idler Selected Essays (US link). They’re better than almost all modern journalism, and are full of great lines like, ‘The essence of poetry is invention’ and ‘Probably no-one will ever know whether it is better to wear a nightcap or not’.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know about it. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

I ordered Johnson on Shakespeare. I have not read any Johnson and you've whetted my appetite.

My literary exposure to Johnson is from the beginning of Vanity Fair, in which Becky Sharp tosses his dictionary out the coach window as a last rebuke to her first enemy, the unpleasant headmistress of the Boarding School who worships Johnson. So that was a negative influence for me on Johnson. Strange how we develop opinions sometimes with such scant evidence!

robertsdavidn.substack.com/about

What I like about Damrosche is that it gives a picture of the intellectual world in which Johnson moved. I was not thinking merely of his essay on Johnson. In our compartmentalized world, we often forget such a rich mixture of people and specialities existed. In Andrew Roberts' "The Last King of America" one sees Johnson working in the King's library, which he opened to scholars and the pleasure the king took in his presence there.