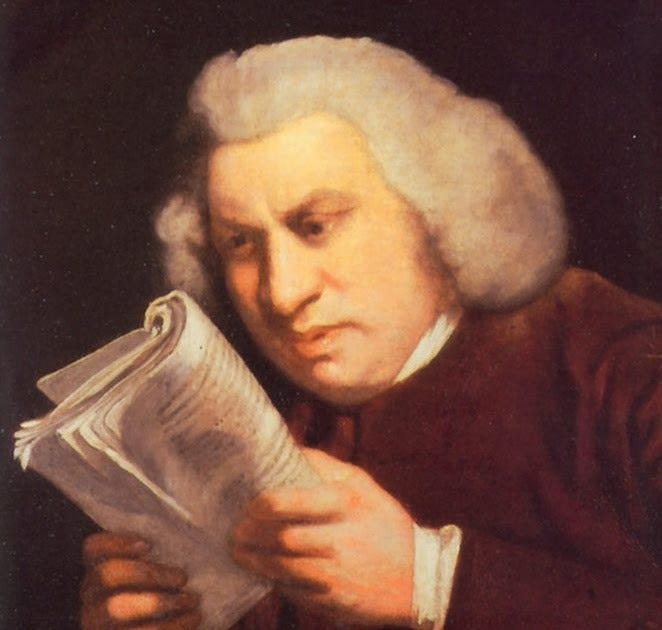

One day, I want to be wise. That might sound corny, but I can think of worse ambitions. The writer I return to, again and again, in that pursuit, is my hero Samuel Johnson. Ever since I started reading Johnson at university, where I was fortunate to have a tutor who really understood him, he has been a crucial part of my imagination.

That’s why I’m very pleased to be hosting a salon about Johnson’s wisdom literature, on 1st March. We’ll be primarily discussing Rasselas, my favourite of his writings, and the Rambler essays. Anyone who attends is encouraged to bring all and any knowledge of Johnson to the discussion. But if you find unforgettable, as I do, Johnson’s exhortations like “you can never be wise until you learn to love reading” or “the only end of writing is to enable readers better to enjoy life or better to endure it” this is the salon for you.

People admire Johnson for many reasons, many of them more pompous than profound. He gets wheeled out by people who just want a high-falutin quote, the way they bring out the dessert trolley at old-fashioned restaurants which would be better off operating as museums. He becomes, through this process of sacerdotal incarceration, a caricature of respectability.

The truth is that he often lived a rather shabby life. He was often poor. His twitches and scars meant he was often regarded — and treated — as a freak. He worked in obscurity for many years. He was married, but not always happily. He had what we would call mental health problems. And, alongside his amusingly entrenched and old-fashioned toryism, he was potentially a political radical. “If England were fairly polled,” he told an alarmed friend in 1777, a time of stability under George III, “the present King would be sent away to-night, and his adherents hanged tomorrow.” This put him in an unfashionable minority.

He wouldn’t let a provocation go past unattended. To go drinking or dining with Johnson, you had to be prepared for serious conversation and serious rebuttal. I find it impossible not to feel compelled by his frankness, the extraordinary range of his knowledge, and the fact that, as Walter Raleigh said, “You can never quite predict what Johnson will say when his opinion is challenged.”

He was socially desirable because he was, in many ways, socially unacceptable. What you notice when you read Boswell is that Johnson changes and challenges conventions not because he’s belligerent, but because he is inexhaustibly interesting. He is frank, but not to be controversial; he is pointed, but not to get attention; he is honest.

We need more Johnsons — more pessimists, more disagreeable personalities; but we need these people to exist in a productive tension with society. Too many disagreeable voices today stand in cartoonish opposition to common sense. This was not Johnson’s style. He was often out of step with his times; but he didn’t want to posture against them.

He was, in his ethical arguments, a pragmatist. He wasn’t a myopic writer, a literary type, an insufferable self-regarding flaneur. Johnson had lived: poverty threw him upon experience, and he turned this experience into the material of his genius. “Books without knowledge of life,” he said, “are useless; for what should books teach but the art of living?”

He offered genuine debate.

To read Johnson is to be challenged to think. The Rambler was written with the premise that “men more frequently require to be reminded than informed.” He wasn’t trying to catch attention. His work makes you think for yourself. There are no shortcuts. “By indulging early the raptures of success,” Johnson warns us, characteristically, “we forget the measures necessary to secure it.”

So, if you too want to be wise one day, join us on 1st March. Now is the time. Wisdom is acquired slowly, and against the clock. As Johnson warned us, “He that runs against Time, has an antagonist not subject to casualties.”