Shakespeare and the Poets' War

How the influence of an upstart (and his former self) made Shakespeare timeless

I wrote about Harold Bloom, Silicon Valley, and the nature of ambition for Luke Burgis.

And so we come to Shakespeare’s miracle year. 1599-1600 is when Shakespeare becomes not just the major playwright of his own time but of all time.

So far, we have read plays from Shakespeare’s second phase. He began in the late 1580s, competing with Christopher Marlowe in plays like Richard III. After the plague closed theatres in 1593-94, Shakespeare wrote best-selling poetry, and he came back to the theatre as the lyrical playwright we have encountered in Romeo & Juliet and Love’s Labour’s Lost. In this period he was out-competing the dominant poet of the day Philip Sidney.

With plays like Much Ado About Nothing and A Midsummer Night’s Dream, he became the star writer of romantic comedies. And with the breakthrough of the Henriad he discovered how to take the dark side of Romeo and begin to transform it into something deeper and more troubling. He developed what would become the essence of his greatest work: the ability to meld comedy and tragedy into complex, problematic new forms. And in his history plays he had gone far beyond what Marlowe could achieve.

The first stage of Shakespeare’s development was complete. He dominated the London theatre.

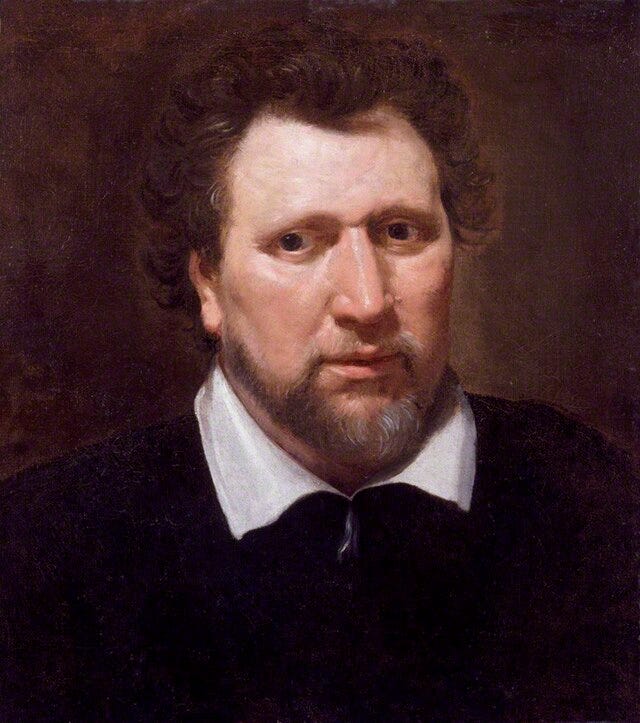

Then came an upstart, Ben Jonson, who, seeing this established and successful rival, eight years his senior, decided to out-do Shakespeare the way Shakespeare had outdone Marlowe. And so, in 1599, the Poets’ War began.

Jonson began writing comedies that were not romantic but satiric. Plays like Every Man Out of His Humour set out a new idea of what drama ought to be. In response, Shakespeare wrote As You Like It, in which he takes Jonson’s new satirical mode and satirises it in the melancholy character of Jacques. (He also disagrees with Jonson’s relatively fixed notion of the self, demonstrating in As You Like It his much more fluid understanding of personality.)

In the next phase of the war, Jonson wrote Cynthia’s Revels and Shakespeare responded with Twelfth Night, a play which blends romantic and satiric comedy much more strongly than any other work, thus showing that Shakespeare can out-do Jonson at both his and Jonson’s mode. Finally, in Troilus and Cressida, Shakespeare writes a dark, nihilistic play, in which Ajax represents Jonson, who is thus purged.

This is the account given by James P. Bednarz in Shakespeare and the Poets War, a fascinating if sometimes over-written book that works through a series of carefully traced allusions between Jonson, Shakespeare, and their contemporaries. The essence of the dispute is that Johnson portrayed characters as types, based on a humour:

Some one peculiar quality

Doth so possess a man, that it doth draw

All his affects, his spirits, and his powers,

In their confluctions, all to run one way.

Whereas Shakespeare represented characters as true individuals. Thus the pinnacle of this Poets’ War was Hamlet, the play in which Shakespeare produced his most unfathomable character.

This battle of ideas with Jonson is a crucial step in Shakespeare’s development, forcing him to absorb, overwhelm, and then reject the influence of Jonson. In just two or three years, this meant he wrote As You Like It, Julius Caesar, Hamlet, Twelfth Night, as well as Merry Wives and Troilus.

Now the lyric phase is over. Shakespeare bettered Marlowe, bettered Sidney, bettered the lyric poets, bettered Jonson—who was out to better him—and he went on to write Lear, Othello, Macbeth, Antony and Cleopatra, and the late romances.

Shakespeare had another rival influencing him in 1599-1600 too. Himself. As Ted Tregear shows in Anthologising Shakespeare, released last year, Shakespeare’s work appeared in no fewer than five anthologies at this time. Commonplace books were popular. Readers copied out passages into their own compilations, sometimes dozens of lines long. This was not a way of gathering a collection of pretty verses, or a garden of verses as we might say, but, following Seneca, Erasmus, and others, a culture of extracting the best parts of a work the way a bee takes nectar from a flower.

Playwrights did it, too, frequently quoting lines of philosophers like Seneca as a means of having their characters think on stage. One way in which Shakespeare develops is to have fewer of these quoted lines and more of his characters “overhear themselves” as Bloom said. Richard III talks about himself at the end of the play; by the time of Macbeth, it is happening right from the start. Whereas the intellectual Jonson was having his characters play with ideas, Shakespeare was re-creating the true process of thought, an enactment that would become central to the great works of Milton, Wordsworth, Proust, and so many others.

Shakespeare knew he was writing for readers who would anthologise his work (contrary to the tired old saw that he was “written to be performed”) and he knew his readers were seeing his old work in anthologies. London was full of educated people, thanks to a large expansion of grammar-schools. His audience was looking for the best new writing, making a canon of the moderns rather than the ancients. The books coming out in 1599-1600 had his work from five, six years before. Work he had left behind was reappearing in this City that was constantly busy with words, words, words.

So he had the additional influence of competing not just against Jonson but against his former self.

The power of influence is strong on creative minds. The feeling that you have come too late, what Walter Jackson Bate called “the burden of the past”, is a strong motivator to find new, original ways of writing. Harold Bloom described the way poets deny the strength of these influences, setting out in Freudian terms the way a poet would unconsciously battle with their precursor and influencer to create original work. Shakespeare became popular by doing that with Marlowe, but in 1599 he became timeless by defeating Jonson as he tried to overcome Shakespeare’s influence and by going into battle against his former self.