Simplicity is a technique, not a style guide.

Eric Hoffer and art as the purgation of superfluities.

Writing elsewhere

My latest Man Made Wonders column, at The Critic, is about Fens reclamation, Thames embankment, and England as a nation of drainage engineers.

Book Club

The next book club where we will discuss Elizabeth Gaskell’s life of Charlotte Bronte will be on 9th July at 19.00 UK time. If you cannot make this time but would like to attend, email me or leave a comment.

Discussing Orwell’s writing rules, you are often up against the argument the simplicity is better than baroque complexity. I do not believe that represents the true difference between the Orwell and non-Orwell side of the debate—simplicity doesn’t mean short or basic—but I struggled to find a way of adequately expressing this idea.

Today I read this from Eric Hoffer’s notebooks:

In products of the human mind, simplicity marks the end of a process of refining, while complexity marks a primitive stage. Michelangelo’s definition of art as the purgation of superfluities suggests that the creative effort consists largely in the elimination of that which complicates and confuses a pattern.

Now, Michelangelo is hardly the Strunk and White of architecture. Quite the opposite. This argument doesn’t say that the pattern has to be unadorned, basic, spare or anything similar. The injunction to purge the superfluous leaves wide scope, depending on your artistic aims. It helps you achieve a pattern of whatever level of complexity you wish: it does not mean you must remove all forms of complexity: it is indifferent to whether the pattern is ornate or not. Sometimes complexity is messy and frivolous; sometimes it is necessary to make a vision clear.

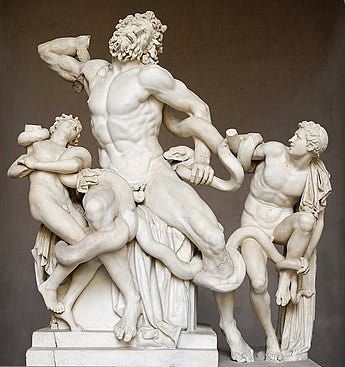

Michelangelo was the creator of Mannerism, a pre-baroque style of complexity. He was inspired by the Laocoön, a sculpture where all superfluous details are removed, but where what remains is still a convoluted event, shown by a complicated but not confusing pattern.

Michelangelo’s dome at St Peter’s, with double columns on the outside, need not have those columns visible—this is the simplest version of the pattern he was making, not the simplest pattern possible. Beethoven re-wrote and re-wrote the opening of the ninth, to make the tune as simple as it could be, not as simple as any tune can be. This is why Orwell breaks his own rules in the rules: he was writing in a particular style, as simply as that style allowed.

The rules of simplicity are a technique, not a style guide. As Hoffer said,

It is the Frenchman’s readiness to exaggerate that is at the root of his intellectual lucidity and also of his capacity for acknowledging merit. The English were not afraid to exaggerate in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and they were then not far behind the French in the lucidity of their thinking.... There is hardly a single instance of cultural vigor marked by moderation in expression.

Sometimes the choice is not between the simple and the complicated but between vigour and moderation.

Paid subscribers get extra essays, like this one about J.S. Mill, genius, and education. They also join the Common Reader Book Club. Last time we discussed David Copperfield and subscribers got my essay and video about the context of the novel, its relation to Dickens’s life, his stinking antifeminism, and how Copperfield encodes Carlyle’s idea of heroes, something I think critics have overlooked.

Complexity for the sake of complexity, and certainly Baroque complexity, obscures rather than clarifies. The finished product needs to be only so complex, and no more. Hoffer's note about Michelangelo's "purgation of superfluities" brings to mind an apocryphal remark attributed to Michelangelo, about the difficulty of sculpting his David. He was supposed to have said, quite modestly: "It's easy. You just chip away the stone that doesn't look like David." This idea of paring away naturally applies to sculpting, in which you subtract until you reach the ideal form; and the witticism has been repeated often in various contexts; for example applied to poetry and life:

"It is the sculptor’s power, so often alluded to, of finding the perfect form and features of a goddess, in the shapeless block of marble; and his ability to chip off all extraneous matter, and let the divine excellence stand forth for itself. Thus, in every incident of business, in every accident of life, the poet sees something divine, and carefully scales off all that encumbers that divinity, and permits it to be revealed in all its transcendent loveliness."

https://quoteinvestigator.com/2014/06/22/chip-away/

I prefer George Sand's remark on the artist's quest for simplicity: "Simplicity is the most difficult thing to secure in this world; it is the final limit of experience and the ultimate effort of genius."

This is what so many writers don't understand. The writing style should adapt to whatever it is you're writing and same goes for other forms of art.