Writing elsewhere

I reviewed a reissued Rose Macaulay book They Went to Portugal for Prospect’s summer issue. What I haven’t written about for some time is homeschool. That’s because my wife now has a blog about that subject,—and she actually does the homeschooling. So if you’re interested, head over there. It’s really quite good.

Book club

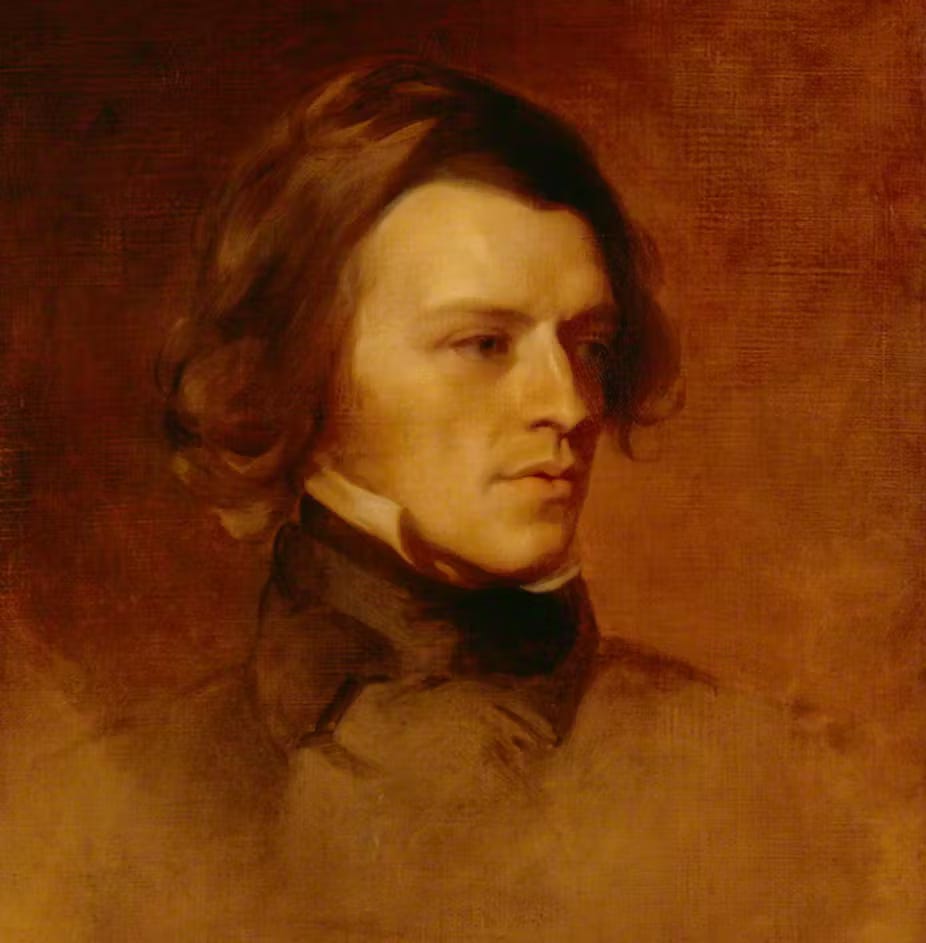

The Tennyson book club is on 10th August, 19.00 UK time. We are discussing the Morte d’Arthur and the final book of Idylls of the King, ‘The Passing of Arthur’, in which Tennyson expanded and altered the original. I’ll also have something to say about The Lady of Shallott. You should also read ‘The Epic’ the short poem that frames the Morte d’Arthur.

Introduction

In anticipation of our forthcoming Tennyson book club, this is the first essay I shall write about the great Laureate. The next one will be about Tennyson and Victorian medievalism. There is a lot of good modern criticism about Tennyson’s career, his sales figures, and his circle. Today I’m going to summarise some of that research to give a picture of Tennyson’s fame. We’re going to see how exactly he became the most famous Victorian poet. As you’ll discover, it takes more than just writing great poetry.

This essay is for paid subscribers. The first few paragraphs are free to see but after that there is a paywall.

Tennyson’s fame

Tennysonians in 1842

“Every body admires Tennyson now, but to admire him fifteen years ago or so, was to be a Tennysonian.” So said one reviewer in 1859, on the publication of the first four books of Idylls of the King (‘Enid’, ‘Vivien’, ‘Elaine’, and ‘Guinevere’.) Tennyson’s breakthrough year is traditionally supposed to be 1850, when he published In Memoriam and became Poet Laureate. But the Tennysonians had been enthusiastic since at least 1842, when he published Poems in two volumes. And they weren’t such a small band as the reviewer above makes them seem. The 1842 book became a word of mouth success, steadily establishing Tennyson as a major poet, who sold more books than he or his publisher expected.

And no wonder. The Poems of 1842 is the book with some of his most enduring work: ‘Mariana’, ‘The Lotos Eaters’, ‘Ulysses’, ‘Locksley Hall’, ‘Sir Galahad’, ‘Break, Break, Break’ and, of course, ‘The Lady of Shalott’. So many of these poems have been quoted by later poets, memorised by schoolchildren, referenced in films. They are so often the poems people name when they enthuse about Tennyson.

Sensational print runs: from five hundred to five thousand

Tennyson’s first collections, a decade earlier, had smaller print runs of a few hundred copies. The 1842 collection started with a run of eight hundred. Then word spread. Print runs increased in size. In 1848, two years before In Memoriam and the Laureateship, a run of three thousand copies was made. Another run of the same size was made in 1850. In 1853 there was a print run of five thousand copies. When the first run sold five hundred copies in a few months, Tennyson and his publisher Moxton thought it was “sensational.” Imagine how they felt when they started print runs in the thousands.

To capitalise on this growing following, Moxton started making more decorative editions, a relatively new idea. The new decorative edition was advertised under the title ‘Books for Presents.’ (You can find many more details on this topic in Tennyson and Mid-Victorian Publishing by Jim Cheshire, a splendid piece of research based on close study of archival resources.)

All this was helped by the success of The Princess in 1847. But sales of the 1842 collection were consistently higher than those of The Princess, Maud, or In Memoriam. Those later poems made more splash, with an initial spike in sales, but the market that was formed for the young poet’s work show Tennyson was truly a poet of the common reader, who built his reputation from the steady sales of an exceptional book by a relatively unknown poet. It was through the 1842 collection that he built the audience who surged to read In Memoriam, Idylls of the King, and Enoch Arden. By the 1860s he was selling books the way they used to do in the Romantic period. The poetry boom was back. And it was Tennysonian.

The aloof genius stoops to sell

The gathering fame of 1842 didn’t quite come out of nowhere, though. Responding to a hostile critic in 1834, Tennyson had said he would rather sit quietly in the garden than sully himself with the great world of literature. Taking his cue from the Romantics who inspired him as a young writer, he professed that popularity was vulgar and genius was for posterity.

That’s what he professed, but not quite what he practised. You don’t become as famous and respected as Charles Dickens,—and Tennyson was eventually that famous,—by sitting quietly in your garden and disdaining to grubby your hands with the literary world. The 1820s had seen the rise of the literary annual, a new popular medium of anthologies of poems, stories, engravings, and essays. The mass market for literature was opening up. The financial crash of 1825 led to the failure of some of Romanticism’s prestigious publishing houses. The elite expensive market was broadening its audience and cheapening its product.

Writers loved to scorn these annuals—while publishing their work in them. And why not? In 1824 Literary Souvenir sold six thousand copies in two weeks. In 1825 it sold fifteen thousand. And the money could be good. Walter Scott got £500 for something he published like this in 1829. His high-minded dislike of the magazines had a price. Tennyson was the same. He said such publications involved neither honour nor profit: they were run by aristocrats who saved the big money for the big names.

Still, he published in them.

He was most active in the 1830s and continued publishing there until 1851. Suddenly we can see that the steady accumulation of his fame after 1842 had been in motion for a lot longer, thanks to Tennyson submitting to the indignities of these annuals. (For more details on the annuals, see Tennyson and Victorian Periodicals by Kathryn Ledbetter.)

Audience segmentation in the 1830s

The annuals were popular with young women. Victoria bought them as Christmas presents in 1837. Engravings were usually of young ladies, to encourage the audience to identify themselves with the product. This was the new audience for poetry and the annuals were well-targeted for them. Any modern marketing expert would do the same. At Cambridge, Tennyson idealised Wordsworth writing for a select group of admirers. But the old ideal of an aloof genius was giving way to the grubbing reality of the nineteenth century market.

The annuals were also a boon for common readers. They promoted the short story form, made a market for engravings, published women authors, and developed a new publishing economy that would be so critical to the literature of the nineteenth century. Readers were getting a greater variety of affordable material.

It wasn’t Tennyson who caught on to this trend though. While he was biting his nails about the risk of popularity, his friend Arthur Hallam was submitting his work for him, as Sylvia Plath later did for Ted Hughes.

What price fame?

You can see then that while Tennyson benefited in terms of sales, he was also creating the conditions for his own fame, which he felt ambivalent about to say the least. Byron had been famous for his indulgent, improper behaviour; Tennyson was going to be the celebrity of Victorian probity and tradition. But that didn’t allow him to live a quiet life.

After In Memoriam was published, his first confessional work, the market for Tennysoniana opened up: biography, pictures, gossip. He got fan mail asking for autographs and letters from lowly, hopeful editors asking for poems.

When he lived in Twickenham in the early 1850s, he was bombarded with unwanted visitors and told the Brownings he wished he could “escape the dirty hands of his worshippers.” An 1860 article about routes to walk along the south coast to see the homes and haunts of poets ended by recommending Freshwater, where Tennyson lived on the Isle of Wight, as it was a “most neglected corner.” The fact that Tennyson lived there was printed in guide books to the island. We don’t know how many people turned up,—Tennyson had moved beyond the railway,—but he wasn’t quite vegetating alone in his garden away from the busy literary world. Things got so bad he built a new home in Sussex and spent his summers there after 1869.

After 1860 there was a rash of “Tennyson At Home” articles, reprinted and rehashed into the 1890s. Private letters were plundered for gossip. “Tennyson at Home: Drinking, Smoking, and Reading His Own Poetry” was written after a letter from a visiting author was shown to a “literary lady” who scurried off and printed the not-very-scurrilous story. An irritation, no doubt, but a contribution to the poet’s fame—and sales. He seems to have collaborated, at least tacitly, with one such article. (For details, see ‘At Home With Tennyson’, by Charlotte Boyce, in Victorian Celebrity Culture and Tennyson’s Circle.)

Life had changed. There was no possibility to be a remote genius. The market for poetry was back and it was closely bound up with Tennyson’s biography. Alfred Austin once said that Tennyson’s fame increased as the quality of his poetry declined. As a Tennysonian, I feel bound to say that that’s not quite true, but his career certainly owed a lot to both the poems and the publicity of the 1842 volume.

Published at the end of his life, these lines were written in the 1830s, before the fame, but prescient of it and its consequences.

What is true at last will tell:

Few at first will place thee well;

Some too low would have thee shine,

Some too high — no fault of thine —

Hold thine own, and work thy will!

The meter of the final quoted poem is weird. All monosyllables, 7 per line. What’s going on?

Nice piece, thank you. Alexander Macmillan was a huge fan of the Poet - when Maud came out in 1855, he took an afternoon off work to slip away and lie in the fields near Grantchester to read it. He also held a public reading in Cambridge at the Alderman’s Parlour, concerned that the piece had been badly received in the press. One audience member wrote ‘All who were present did not fail to appreciate the grand aim of the poem, and as a work of art worthy of much earnest study. We trust Mr Macmillan will be induced to give another public reading, when we can promise our readers an evening of rich and choice instruction.’ He was Tennyson's last and favourite publisher, finally clinching the deal in the 1880s: it meant a huge amount, as he wrote to Emily Tennyson 'It is just forty-two years since I first read “Poems by Alfred Tennyson” and got bitten by a healthy mania from which I have not recovered and don’t want to recover. I then tried to bite others, with some success. I have now other, I cannot say deeper motives for continuing the process. How much I owe to Alfred Tennyson for the increase of ennobling thought and feeling, no one can tell. Now our closer connection will not lessen my desire to repay the debt.'

For a very funny account of the Tennysons' desire to avoid fans in Farringford, their home on the Isle of Wight, try Lynn Truss, Tennyson's Gift

https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Tennyson_s_Gift/SJjZDlTWnpgC?hl=en&gbpv=1