The Biographies of Westminster Abbey

And in the handywork of their craft is their prayer.

You enter Westminster Abbey by the north door. Ahead of you is a desk to collect the dreaded audio guide, before you walk down the north aisle beside the nave. To your immediate right there is a recess with a desk where you can buy guide books. This area contains many memorials that are roped off. Fortunately, when I visited most recently, no-one was looking or seemed to mind that I went through the rope to see who was being neglected in this corner of the abbey.

These memorials are to people like the Earl of Halifax who raised a regiment against the 1745 rebellion. Or Francis Horner, whose statue says, he had a short but useful life and “expectations which a premature death alone could have frustrated.” This statue may not have achieved quite what it was intended to as it is now stuck behind a blank portable sign holder of the sort that might hold posters directing you to the gift shop or restaurant. There was also Joshua Guest, a sixty-year-old General who died fighting at Edinburgh Castle in 1745. His memorial is half-blocked by shelves and cupboards. Closer to the desk, and much more visible, is Elizabeth Warren, distinguished for the purity of her taste, soundness of her judgement, and extensive charity work. Those not on audio tour auto-pilot might just about see her as they go past.

One of the joys of the abbey is that it is a huge compendium of this sort of biography. But having a memorial in the nation’s premier church isn’t all you would expect. People like Philip de Sausmarez, who joined the navy at 16 and died aged 37 fighting the French on board the Nottingham, get full prominence. Poor old Samuel Arnold, organist and composer to the Chapel Royal, had a large storage trolley parked on top of him.

Still, there’s something democratic and meritocratic about the way memorials are cluttered together. Unlike modern minimalist styles of curation, the abbey uses almost every inch of space to accommodate the memorials. You see this levelling spirit taken perhaps too far in the stone laid down for Darwin. All it says is, “Charles Robert Darwin, born 12 February 1809 Died 19 Apr 1882.” Next to him is Florey, whose work on penicillin is remembered. Nearby is a book with names of the members of the Women’s Voluntary Service who died in WWII, and of whom there is apparently no other record.

What is recorded is often not information about the life, but about the character. The emphasis is on the person, the timeless. Mary Beaufoy’s monument was put up by her mother. It says the mother will lament the loss of her daughter while-ever she lives, and it goes on: “reader, who ere thou art, let the sight of this tombe imprint in thy mind, that young and old (without distinction) leave this world: and therefore fail not to secure the next.”

On that point about all of us leaving this world, some of the tombs in the floor, especially by the altar, are wearing away. Dame Mary Willes and her husband are getting unreadable. The one next to them, Edward Willes, is so worn away it must be beyond repair. There comes a point when just to have your name recorded is perhaps enough. You might think this potent reminder of mutability — that even a socking great carved marble memorial in a thousand year old church will not last — would bring out the tourists with a chill of recognition that their time, too, is limited. I noted no such concern among my fellow travellers.

One of the most admirable lessons of this clutter of tombs is that there is value in biographies of all lives, not just impressive ones. Lloyd George gets more than Darwin, with “Prime Minister” on his tablet. But he got nothing compared to the memorial close by, to one James Bringfeild, equerry to Prince George of Denmark and aide de camp to the Duke of Marlborough. This is a long descriptive monument, which tells us that James,

while he was remounting, his lord, upon a fresh Horse, his former Fayling under him, had his head fatally shot by a Cannon Ball in ye Battle of Ramelies, on Whitesunday ye 12th day of May in ye Year of our Lord 1706, and of his age 50: and so haveing gloriously ended his days, in ye Bed of Honour, lyes interred at Bavechem in the province of Brabant, a Principal part of of ye English Guards, attending his obsequies.

James’ wife, Clementine, had the monument put up. There are, in many senses, tombs of unknown soldiers all over the Abbey. One tablet near the north door simply reads “Ann Oldfield 1730.” Of course, there are politics behind such things. Ann Oldfield was an actress. Her partner wanted a monument but the dean refused, probably because she was an actress with an unmarried partner. Biography can be — and should be — concerned with such things. But it is nice to see memorials to people much less acceptable and distinguished than the great and good getting as much space as them. Would it be much better for her memory if Ann’s memorial included the word “Actress” as Betjeman’s includes “Poet”? He will be forgotten in time, no doubt.

Many wives are commemorated. Anne of Cleeves gets a rather more dour position than you might expect. Much more pleasing was the stone for Anne Cranfeild:

Under this stone lyeth interrd the body of Anne Cranfeild second wife to Lyonel Earle of Middlesex Lord High Treasvrer of England shee departed this life the 3rd day of Febrvary in the year of our Lord 1669

All that flummery doesn’t really do much more for her than Ann Oldfield’s plainness. Once a life is reduced to its bare facts, the status you are trying to preserve is flattened out. Biography is a great leveller, irrespective of the style of the tomb. For all the grandeur of being interred in a place of saints and monarchs, Ann Cranfeild and her husband are still sharing their resting place not just with Elizabeth I and Edward III, but with Thomas Parr.

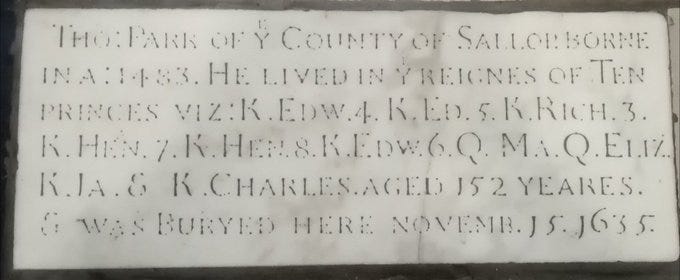

Tho: Parr of ye count of Sallop. Borne in A. D. 1483. He lived in ye reignes of ten princes viz: K. Edw. 4. K. Ed. 5. K. Rich. 3. K. Hen. 7. K. Hen. 8. K. Edw. 6. Q. Ma. Q. Eliz. K. Ia. & K. Charles. Aged 152 years. & was buryed here November 15. 1635

Of course, he wasn’t that old. But his story is instructive. Parr was thought to be eighty when he married. He lived on a simple diet, worked hard, and slept well. He did penance for committing adultery when he was 102 and married again, aged 122, after a decade as a widower. He was known to be sexually active with his wife until well into old age. When he was “discovered” by Thomas Howard, fourteenth earl of Arundel he was taken to London as an exhibit. He was blind and had only one tooth by this point, so his incredible age was probably believable, especially at that time. “In a semi-literate society the exaggeration of age was a common practice, particularly when it brought people attention and respect,” says Keith Thomas in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Parr was quite a sensation: crowds gathered to gape at him as he travelled to London.

In London, Parr was put on show. He had his portrait etched by Cornelius van Dalen and was presented to Charles I. Disappointingly, he proved able to recall very few of the public events of his long lifetime, being more interested in the price of corn, hay, cattle, and sheep. Six weeks after his arrival in London he died suddenly, on 14 or 15 November 1635.

He was thought to have died from exposure: London offered rich food and drink, pollution, animals, smoke. This was all too much after a lifetime of clean, stern Shropshire living.

Parr’s story shows us that memorials can be a question of credibility. Thomas Parr and Anne Cranfeild are both in the abbey because someone, many people, wanted to believe in their worth. Earls and Countesses are no more real than men of biblical ages. No records have been found to corroborate Parr’s age. And there is yet no way of proving a a man or woman is anything more than a man or woman, no matter who they married or what political function they perform or what ritual they go through.

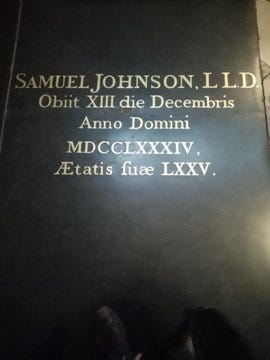

But the abbey isn’t just a place of status, a national game of who gets the biggest slab. It’s an architectural book of brief lives carved in stone and the fact is that almost everyone in there did something memorable. Anne Cranfeild’s life, married for an allegiance, was surely one of work as much as anyone else’s. The whole abbey is a monument to work, a testimony of labour. That is why poet’s corner and the shrine of Edward the Confessor and James Bringfeild and Elizabeth Warren are all together. ‘Every man,’ says Samuel Johnson, ‘may expect to be remembered in an epitaph.’

In the Chapter House, one of the wonders of England, there is a quote from Ecclesiastes in the stained glass, which says, “But they will maintain the fabric of the world; And in the handywork of their craft is their prayer.” A fitting sentiment, and one that shows why we ought to memorialise everyone from organists to saintly kings to actresses to lexicographers to charity workers to generals who die in the defence of their country to wives married for political reasons. Everyone, as Ecclesiastes says, is wise in his work and without them a city cannot be inhabited

Of course, I went to see Johnson’s tomb .

And I recently visited Dr Johnson’s House, the museum in Gough Square of the house he lived in when he wrote the dictionary. It’s a splendid museum and I recommend it to you all. While there, I was shown a book Johnson owned. You can see the watermark left by a tankard or mug on the C17th edition of Seneca’s plays in the picture below. Johnson treated all his books in this fashion, if not worse. It was a real privilege to see this, complete with his marginal lines. If you want to know more about Johnson at Gough Square, read Dictionary Johnson by James Clifford.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

Delightfully interesting. Reading this was like taking a personal tour and I could almost hear our footsteps echo as we passed through the various chambers. Thank you.

Thanks, Henry. This was beautifully written.