The case for opsimaths. Maybe late bloomers aren't so late

Late bloomers and lifelong learners

UPDATE: My book about late bloomers Second Act: What Late Bloomers Can Tell You About Reinventing Your Life is available for pre order.

Amazon UK. | Amazon US. | Amazon Canada.

In 1953, when he was 45 and had been working at the National Trust for twelve years, saving country houses that would otherwise have been destroyed, James Lees Milne wrote in his diary:

I love my country house tours more and more as I grow older and become more and more fascinated by persons, places and things. I am a late developer more than most men of my generation and in some respects still quite adolescent, an opsimath indeed.

In 1931, Lees Milne had left Oxford with a third-class degree and few prospects. By the end of his life he was a pillar of the National Trust, who had acquired many of the great houses the Trust now owns, as well a celebrated diarist, and the author of one of the best English memoirs ever written. His career at the Trust started when he was in his twenties, but got interrupted by time in the army, which ended with him being invalided out. So he went back to the Trust, a disappointed man in his mid-thirties.

At this point, he had a double revelation: one religious, one architectural. As well as converting to Catholicism, he realised he had a ‘deep atavistic compassion for ancient architecture so vulnerable and transient’, and decided to devote his ‘energies and abilities, such as they were, to preserving the country houses of England’.

He believed that his mental faculties were better in his forties — when his hair was falling out and his libido was failing him — than they ever had been.

Milne was right; he was a late developer. But he was wrong to think of it as late. Different sorts of people realise their abilities at different stages of their lives. This is consistent with recent research on the ages at which different cognitive functions peak throughout our lives. (More on that below.)

This view of development is starting to become more widely appreciated. But it is by no means well established. In deeply meritocratic industries like tech I suspect it’s easier to get a break despite your background. Organisations like Lambda school show that. But my experience of working in the talent attraction industry is that, on the whole, companies want to hire based on proven experience, rather than potential.

We are not very good at knowing how to assess people who have not yet succeeded but who might become impressive later on. Why do some people show no sign of their later promise, and how can we think about the lives of those late bloomers who had precarious journeys to their eventual flourishing?

This is not something unique to one profession or period of time. It is becoming much more recognised that some people bloom later for inherent reasons, not just because of external circumstances. We ought to find this less remarkable than we do — and feel less of an instinct to explain it. It is, in fact, quite normal.

Biography can be a way of helping us to see the variations of when people excel. And writing biography explicitly about late bloomers can help us to think differently about how we assess and define development. We need more lives of people who wouldn’t have been picked out as successes earlier on. And we need to understand those people better and find other ways of framing them than as simply ‘late’.

The people I am interested in are usually opsimaths. That strange, attractive word Lees Milne used to describe late bloomers really means someone who learns throughout their life, or who begins learning later on. Rather than a Romantic idea of genius, the inward lamp that burns intently from a young age, this is a gentler, more perpetual idea of development.

In his short autobiographical essay, David Hume said about his life:

‘In 1734, I went to Bristol, with some recommendations to several eminent merchants, but in a few months found that scene totally unsuitable to me. I went over to France, with a view of prosecuting my studies in a country retreat; and I there laid that plan of life, which I have steadily and successfully pursued.’

‘Steady and successful’ is a template we often feel the need to explain as late or slow. But for many people, the reasons for flourishing later on are not complicated, they are natural. A growing area of study suggests all sorts of reasons for this.

A famous article by Malcolm Gladwell, about the story of late blooming writer Ben Fountain, started a new trend of thinking differently about success. Gladwell cited an economist at the University of Chicago, David Galenson, who has studied creativity. He uses poets like Frost, Williams, and Stevens to show that, contrary to common belief, writing lyric poetry is not a talent reserved to young people. His work has a neat comparison between Picasso, who produced masterpieces from a young age, and Cézanne whose best work was done at retirement age.

Galenson points to the imprecise goals of late bloomers, who work over things again and again, refining them as they go. This is the opposite of the prodigal Mozart types who seem to emerge as complete talents when they are in their late teens or early twenties. Picasso was ready to express his vision young; Cézanne came to his vision through repeated attempts at expressing it.

Other books are following the way. Range by David Epstein argues that you don’t have to specialise early to succeed — quite the opposite. Generalists who specialise later on can be more successful. More recently, Late Bloomers by Rich Karlgaard (US link) is a review of the new research in neuroscience that makes late blooming seem quite normal. It is not always rational to expect great things exclusively from the young. Ageing often means advancing.

Scientific work has shown that while fluid intelligence declines relatively young, concrete intelligence continues to strengthen until much later in our lives. The distinction between fluid and concrete intelligence (the difference is between dealing with novel problems vs being expert in something) is a blunt one. But it does help us see clearly that we are better at the sort of thinking that assimilates and responds to new issues better when we are young. This is, for example, why poets are often very young but few historians are.

However, we now know that people peak cognitively for different abilities at different ages. Hidden within the averages above are some significant variations. Raw speed in processing information appears to peak around age 18 or 19. The ability to recognise faces improves until your early 30s, as does visual short term memory. Evaluating other people’s emotional states peaks in your 40s or 50s. Vocabulary can peak as late as your 60s or 70s. You can see from this table that there is considerable range in when various functions peak.

One study has concluded that ‘conceptual poets, conceptual novelists, experimental poets, and experimental novelists… do their best work at ages 28, 34, 38, and 44, respectively.’ This mirrors the fluid/concrete intelligence finding. Conceptual artists are like Picasso and Mozart, born with a vision. Experimental artists are like Cézanne and Beethoven, they develop their abilities through practice.

I’m not sure how useful it is to average out things like this for creative artists, but it certainly shows that we ought to be much more open to the idea that people’s best work can be done at any stage of their lives, even if they are doing highly unique, incommensurable work. The fact that Jane Austen wrote her best novels before she was twenty five tells us nothing about how we ought to assess other novelists’ lives. Our expectations of when authors will naturally start producing ought to be revised.

A similar result has been observed in entrepreneurs. The paper ‘Age and High-Growth Entrepreneurship’ found that, contrary to popular assumptions, ‘The mean founder age for the 1 in 1,000 fastest growing new ventures is 45.’ Just like with poets and novelists, not all tech founders are young.

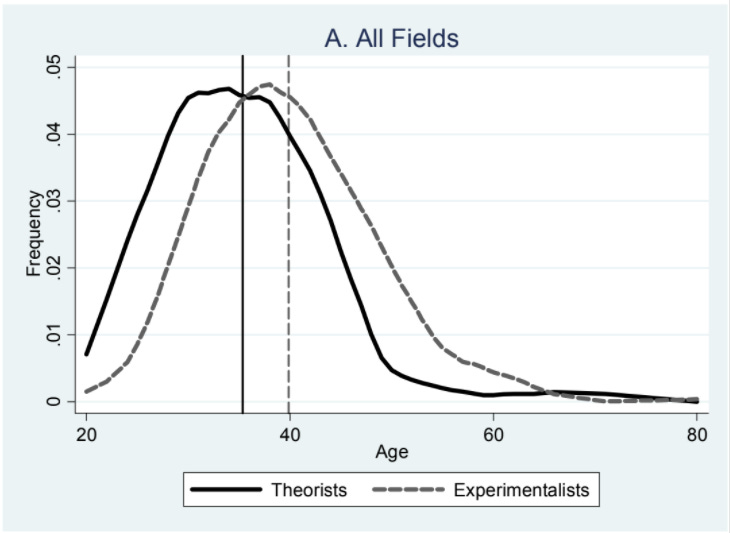

Scientific success has typically been associated with middle age, and in physics was thought to be strongly correlated with youth. Recent work has shown it to be evenly spread across people’s lives. As Jones, Reedy and Weinberg remind us, ‘Copernicus completed his revolutionary theory of planetary motion around age 60.’ The difference between conceptual and experimental thinkers we saw in writers is also seen in Nobel prize winning scientists, with the average age for empirical winners being older than that of theoretical winners.

A study of when scientists publish their highest impact work found that scientists are just as likely to do their best work old as young.

We find that the highest-impact work in a scientist’s career is randomly distributed within her body of work. That is, the highest-impact work can be, with the same probability, anywhere in the sequence of papers published by a scientist—it could be the first publication, could appear mid-career, or could be a scientist’s last publication. This random-impact rule holds for scientists in different disciplines, with different career lengths, working in different decades, and publishing solo or with teams and whether credit is assigned uniformly or unevenly among collaborators.

The important conditions for scientific success are a combination of ability and environment, luck, and, importantly, persistence. Once scientists have prestige and tenure, they tend to produce less work. The ones who keep going are the ones who bloom late. Nobel prizes are awarded for work done at all ages.

Luck is essential. Choosing the right project at the right time matters. But once that opportunity comes along you also need a series of other factors in place.

Turning that fortuitous choice into an influential, widely recognized contribution depended on another element, one the researchers called Q.

Q could be translated loosely as “skill,” and most likely includes a broad variety of factors, such as I.Q., drive, motivation, openness to new ideas and an ability to work well with others. Or, simply, an ability to make the most of the work at hand: to find some relevance in a humdrum experiment, and to make an elegant idea glow.

When you get your break is just as important as whether or not you have the abilities to make the most of it. Importantly, the Q factor, life long persistence, and luck, are independent of each other. Highly productive people who lack Q will not be successful, for example, in the way that people with both are.

What we see here is that lifelong learning is essential. Late bloomers in this model are really opsimaths who got a break.

There are many lives we can look to as illustrations of these principles. Biography has been through phases of applying other models in the past. Masses of psychobiographies are gathering dust in libraries the world over, valiant attempts to stretch out the details of people lives to fit Freudian theories. More usefully, Parallel Lives by Phyllis Rose tells the stories of well known historical figures in order to illustrate a feminist argument about marriage. This is a less forced, more factual approach that yields provocative results. We might take it as a model for telling the lives of opsimaths.

This is not about a crude application of empirical work (akin to a posthumous medical diagnosis, for example) but a way of reframing how we interpret people’s lives as an example for future opsimaths. Rather than try and use biography to demonstrate these theories specifically, we ought to be looking generally for some core qualities in the lives of late bloomers and lifelong learners.

People with a combination of Q, productivity, and luck

People who continuously learn and/or adapt

People are are ‘experimental’ rather than ‘conceptual’

People who persist

Elsewhere, I have called this ‘The Fitzgerald Rule’: You spot talent by looking at what people persist at, not what persistently happens to them.

Taking the ideas of cognitive peaks, fluid and concrete intelligence, the role of luck and persistence in scientific success, and other recent empirical findings, we should be able to start re-thinking how we write the lives of late bloomers. We might start by dropping the ‘late’ designator all together.

Rather than thinking of people as late bloomers, people who were in some way held back or prevented from success, we would be better off seeing them as opsimaths: smart people who carried on learning and achieved things when the timing and circumstances were right.

Biography’s contribution to this is to contextualise and show the ways in which talent can express itself seemingly out of nowhere. Tracing the factors that were in place before the biographical subject made their achievement, using the general factors detailed from recent empirical research, might offer a useful approach.

These are some examples of how we might think of some well known historical figures as late bloomers, and where we might start to lay the emphasis differently.

Samuel Johnson would have been an unknown hack writer if he had died before he was forty, perhaps remembered by specialists as having been at work on a dictionary. Like many writers, he then had an intense period of creativity, an extraordinary fifteen year period in his forties and fifties. He then became the dominant literary figure of his day, having produced the Dictionary, The Rambler, Rasselas, and Lives of the Poets, as well as his edition of Shakespeare. His accumulation of knowledge, which began from a remarkably young age, didn’t make him a young success. But it meant that when a group of booksellers wanted to find someone to write a Dictionary, Johnson’s network, his reputation for scholarship and philology, and his prodigious knowledge made him the perfect candidate. Johnson’s early life was famously given vastly less space in Boswell’s biography than the period after his achievements. His life has some interesting parallels to another opsimath and lexicographer, James Murray, the first editor of the OED.

Johnson’s biographer Boswell was another late bloomer. Until he wrote the Life of Johnson in his fifties he was something of a joke among his contemporaries; he was also a failed barrister. He was closely mentored on his project by Johnson in an indirect way, and by his publisher more directly after Johnson’s death. There were many occasions when he more or less quit. The Victorians used to think Boswell was an idiot who got lucky by meeting Johnson. In fact, detailed work by scholars showed that his phenomenal memory and unique system of taking notes means he (very loosely) fits the Q, productivity, luck pattern.

Thomas Bayes, whose statistical theory of probability, produced as a riposte to Hume’s theory of epistemology, is now the basis for many of the algorithms used in modern technology, was used as part of the Enigma code breaking, and has been important to the way we approached the coronavirus pandemic. His work was found in his desk after he died. He was a Presbyterian minister who became interested in probability in the last decade of his life.

Edward Jenner, a member of the gentry and a country doctor whose observation of local conditions and interest in variolation enabled him to invent the smallpox vaccine. He was 46 when the first vaccine was administered and 49 when his paper was published. By then he was successful and could have lived a comfortable life. Perseverance and long standing interest led him to his phenomenally important discovery. He is less well known as the man who discovered how cuckoos displaced eggs in other birds’ nests, and was not believed until the twentieth century. His close observation skills were the key to both of his discoveries.

Charles Darwin, a classic opsimath who published his last book in his eighties which remained a major reference work for many years, was the model of the scientific pattern described above: naturally intelligent, highly lucky throughout his life, and incredibly persistent in the face of a hostile (or worse, indifferent) intellectual climate, and terrible health. The role of luck in his story is astonishing, including the escapade of nearly being taken off the Beagle voyage at least once. His delay in publishing his idea meant it was thoroughly supported and defensible with a mass of research. He is a classic example of the Q, productivity, luck model. He had the basic idea of evolution young, but he did the impactful work much later on, after a famous delay. He also produced works on barnacles, worms, and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, works that remained significant, if not the standards, for many years after his death.

Benjamin Disraeli, whose antics during the 1825 financial crash left him with debts that burdened the rest of his life, and arguably coloured his early career decisions. The first half of his career was a disaster and his reputation was fairly low. A combination of talent, luck, persistence, and sheer audacity meant he was able to take his opportunity when it finally came along. The number of outrageous things he did in his youth would be enough to ruin the careers of half a dozen good politicians today. His motto, Forti nihil difficile, means ‘To the brave nothing is difficult’. He could easily have retired at sixty and become an anecdotal footnote: outrageous novelist who was once Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Anne Clough, the first president of Newnham college, had been home educated and left with an interest in reform. She used to get up at 6am, ahead of the household, to teach herself Ancient Greek. Her brother, the famous poet, died young and she looked after his children. She started a pilot school aged 47, and four years later Henry Sidgwick invited her to be president of Newnham. She knew him through her brother. It was the culmination of a lifelong ambition that she had worked at slowly and persistently.

Bonar Law showed very little outward sign of moving towards a political career, despite being highly ambitious, until he was elected at forty. He became Tory leader with no cabinet experience ten years later, showing his political cunning during the campaign. Although a short lived Prime Minister, he took over the party at its lowest ebb, won a big election, and saw the Irish treaty through Parliament. English politics is full of famous rivals who might have been better working together — Pitt and Fox, Disraeli and Gladstone, Thatcher and Kinnock. Bonar Law was disciplined enough to be the junior partner in Lloyd George’s coalition for the second half of the war and for four years afterwards. He could have been Prime Minister but worked for the good of the country. His achievements are bigger than they look. He was deeply ambitious but spent his life before the age of forty in a very strange and unique sort of preparation for political life. His exceptional memory was honed working in iron trading in Glasgow and his oratory was learned at the Glasgow Parliamentary Society and in the Bankruptcy Courts. His hard won, outsider status, his stoic, hard working temperament, and his age contributed to his political patience, the cornerstone of his success.

Alexander Fleming was an outstanding researcher with a good record, but like most scientists with nothing historic to his name. It was his unique combination of excellence, persistence, and sheer good luck that meant he discovered penicillin. It was also thanks to his untidiness, another underrated quality in opsimaths. Other people did the subsequent work to make penicillin into a useable drug, but without Fleming the history of medicine would be very different. He is a model story of the power of oblique success.

Penelope Fitzgerald lived a remarkably difficult life, crowded with misfortune, which showed no flowering of her early promise — a double first from Oxford and a prodigy of the famously literary Knox family. She published her first book in her late fifties and carried on until she was eighty, producing some of the finest novels of the twentieth century. She had a genius for writing about failures and misfits. One version of her life could be that marriage, children, poverty, and her husband’s alcoholism held her back from writing. But she had her children in her thirties and did little to no creative writing before that. Importantly, when she worked as a teacher in middle age she gave herself a second education in European culture, literature, and languages, including widespread travel. She needed the peace that came with later life to write, but she also needed the accumulated experience of her life and her learning to be the sort of novelist she was. Her work is deeply European in form, content, and informed by deep research.

Wendy Cope was depressed from the age of three, always assumed she would be a failure, and while working as a primary school teacher spent over a decade in psychotherapy, attending Saturday sessions in the early years as things were so bad. She eventually went to poetry workshops with Blake Morrison and when she was forty published a book that has sold something like half a million copies to date. She is perhaps the most popular British poet since Larkin. Her time as a primary school teacher engaged her with arts and creativity in a way that her earlier life and education had not. She has been influenced by A.E.Housman, another exemplary opsimath.

Oblique success and lifelong learning are essential parts of many of these stories. And the list could go on. Warren Fisher spent sixteen years at the Inland Revenue, not his first choice, before becoming a long lasting Permanent Secretary to the Treasury, and the first head of the civil service. Lord Melbourne was an otherwise unsuccessful Prime Minister who was able to provide important, if not always correct, advice to Queen Victoria when she became queen. Henry Rolls founded his famous company late in life. The writer Oliver Goldmsith is acknowledged as a late bloomer in The Life of Johnson. Charles Spearman spent many years in the army before starting a PhD aged 34. He later did seminal work on the theory of intelligence, creating the theory of general intelligence. Winston Churchill is so famous a failure there is an entire book about it (Churchill: A Study in Failure (US link)). Julia Child didn’t graduate from cookery school until she was in her forties. Mary Wesley published her first book aged seventy. She sold millions of copies and produced a best seller a year for the next decade. Isaiah Berlin considered himself to be a late developer, coming to the history of ideas in the middle of his career. Thomas Hobbes didn’t begin to study maths or science until he was middle aged. Quentin Skinner has said, ‘This sudden awakening, coming as it did when Hobbes was in his forties, entitles him to be regarded as one of the latest of all the late developers in the history of philosophy.’ I would, of course, prefer to think of him as an opsimath: he didn’t start late, he just carried on.

There are examples, too, of people whose achievements are less acclaimed like William Dawson who was a shoemaker in Hertfordshire, eventually taught himself to become a teacher, and was learning Anglo Saxon at the age of eighty. Among his pupils was one of the early students at Newnham College, Cambridge, who studied with Anne Clough. There is a trend now for opsimath clubs, where people who are learning late in life can get together and share their common interest.

This begins to provide new models for thinking about late bloomers biographically. Do they really need to be explained as ‘late’? Doesn’t that rather assume that successful people tend to show their promise early on? There are many fascinating lives in all spheres who would benefit from this sort of biographical treatment. Hetty Saunders' recent biography of J.A. Baker My House of Sky: The Life of J A Baker is an excellent short case study in how to write about such a subject.

As well as offering a new way of thinking about biography, this is relevant to businesses and people interested in spotting talent. Looking for signs of promise is all too often something we default to in young people, assessing mature people on their experiences so far, rather than the future, unexpressed promise that might be just as strong within a forty or fifty year old as in a twenty year old — if not stronger.

Some of the people listed above have already been profiled on this blog. Some of the others will be the focus of upcoming posts.

James Boswell, wonderful failure

Why did Wendy Cope start publishing so late?

How J.A. Baker became a great writer after showing no signs of talent for forty years

People who haven’t succeeded yet but maybe they will

Those of you who have been reading since the old blog will remember other posts about this topic, which you can find here.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

Brilliant insight.. Such affirmation so delicious to my soul.

Ulysses S. Grant is a classic late bloomer. Maybe you could argue the ability was always there, but it needed the right circumstances to become apparent. I think there is also an argument that he was ASD, and this may have contributed to his lengthy period of being overlooked, and difficulties in advancing himself in the military and business worlds.