Writing elsewhere

For the New Statesman I wrote about why Liz Truss should not set up a think tank. For The Critic I wrote about why Liz Truss will be a Barry Goldwater figure, why it is difficult to imagine modern civilisation without plastic, and what Samuel Johnson can teach us about (not) making New Year’s resolutions.

Salons

I am hosting a salon about biography as part of the InterIntellect Thesis Festival on February 25th. The final instalment of my salon series How to Read a Novel is on February 7th.

What a remarkable book! I wish I had read it when it came out and I was seventeen. Tyler Cowen asked Katherine Rundell this week, “Should the rest of fiction be more like what we call children’s fiction?” Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell achieves something like that, in that while it is for adults, it is a great big gulping book, big in wonder and imagination. It is a very Bleak House of a book. It will remind you of what it was like to read as a child. It has all the immersive and unburdened qualities of books like Narnia, His Dark Materials, and so on, but with the rigour of a very well informed historical novelist. (Susanna Clarke can also pastiche Austen and Dickens astonishingly well.) It shares this deep immersiveness with Donna Tartt, another writer influenced by Dickens and the emergent genre fiction of the nineteenth century.

The writer it reminded me of most was Hilary Mantel, who in her own way was a historical fabulist. There is nothing actually magical in Mantel; but she invokes the speculative, the ghostly, the not-quite-real. Mantel does this as a historian. She shows us her characters’ superstitions, rather than giving them authorial authority. Unlike Dickens, she keeps iron-fisted control over the progression of her story, which is also the root of Susanna Clarke’s talent.

And Clarke (more so than Mantel, I think) is a novelist of power. It is a mistake to think of Mantel as a writer of power, as such; rather she understands that High Politics is as much about interpersonal relationships as it is about strong ideals. Clarke is also interested in that idea, but Mr Norrell is a faustian figure, obsessed by power because of vanity, a slightly different question. Both writers share an interest in the phenomena of the person next to the most important figure being the one with the most power. Being less directly about the sort of power than actually does exist in our world, Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell is a more useful way to study it, much as Macbeth and the witches have more to teach us about ambition than Edward II or Tamburlaine.

This is also a book for the emerging age of AI. The important question for both magic and AI is how you choose to use the new power, if you choose to use it at all. There will be Strangites and Norellites among us too. It isn’t quite right to say that ChatGPT means magic has re-emerged in history after a break of many centuries, as is the premise of this book, but it is a good enough analogy. After all, Clarke writes, “In February 1666 Valentine Greatrakes held a conversation in Hebrew with the prophets Moses and Aaron.” ChatGPT will do that for you, no magic required. The people who used to go to seances will now be training AI on the messages and videos of their loved ones. This book has more to tell us about our future imaginations than we might think.

The footnotes are so admirable because they are a way to tell a story-within-a-story (a technique favoured by Fielding before Dickens and used more recently by Jonathan Coe) but without actually diverting from the main path of the book. Indeed, Dickens would have done well to relegate some of his divergent material to footnotes. One day, perhaps, a sympathetic editor who has read Susanna Clarke will do that for him, using the AI to help make creative decisions. Clarke also keeps her analepsis (and some foreshadowing) in the footnotes, which gives her the freedom of these techniques without making the book unwieldy or sentimental. (That famous Richard II prolepsis, Let us sit upon the sand and tell sad stories of the death of kings is a bit over done, don’t you think?) Foreshadowing is much more enticing in the footnotes, especially when it is in book titles, like lines spoken aside in Shakespeare. Of course, one thinks of Prospero and Ariel often reading this book. My high charms work, and these mine enemies are all knit up in their distractions…

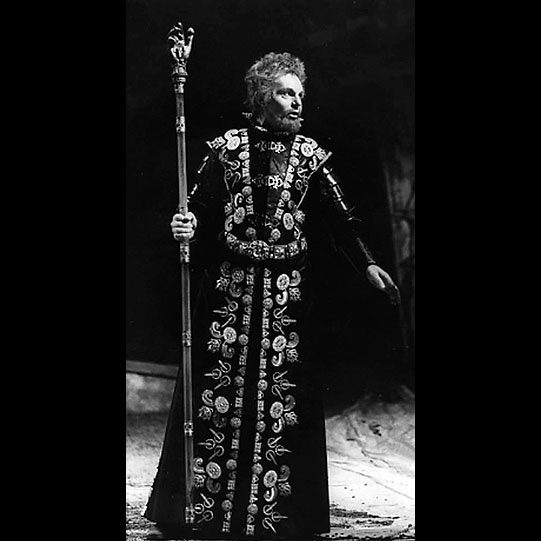

I have ordered Earthsea by Ursula K. Le Guin as it was an influence on Susanna Clarke. If you want to hear some outstanding Shakespeare, listen to this scene with Derek Jacobi as Prospero. Outstanding stuff.

Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

My first foray into Clarke's work was with "Piranesi." It was emotional and small, the perfect afternoon read. It had the charm of Lewis with the theology of Owen Barfield (quite literally).

However, when I finally picked up JS&MN, it was something else entirely! I had so same reaction: WHY DID I WAIT SO LONG, AND HOW DO PEOPLE NOT FINISH THIS NOVEL IT IS AMAZING OMG OMG OMG. You know, something like that. Once again, I am happy to know that you are a fellow traveler, Henry. Keep this kind of posting up.

Jon

Henry, I'm glancing at Jon Beadie's comment below. Perfect! He said everything I thought while reading your wonderful post about the remarkable Susanna Clarke.

This insights was poignant, indeed: "This is also a book for the emerging age of AI. The important question for both magic and AI is how you choose to use the new power, if you choose to use it at all."

Great extension and application of Clarke's work to the ambiguities of digital "power."

Blessings,

Daniel