The Last Days of Roger Federer, Geoff Dyer

The reviews of The Last Days of Roger Federer have been decidedly mixed. Simon Kuper in the FT, for example, thought it was rambling. But that misses the point. This is a compendium book, a series of connected sections, like a diary or anthology, but in this case a set of reflections about decline, some personal, some about tennis players, novelists, and Bob Dylan. As such a book, it is pretty good. The prose is nice, the stories are well told, it doesn’t go on too long, and the topic is interesting. As the LA Times said, it’s a memoir in camouflage. I am not aware of another book quite like it. 1913 has similarities.

But how difficult it is to praise Dyer, because those things that make him a good writer also tempt him into error! There are many subjects, perhaps most subjects, when it just isn’t good enough to be a well-read literary writer with an interest in writing finely turned sentences.

For example. Dyer is nostalgic for the days before railway privatisation, which he says “maximised profit and commuter dissatisfaction.” This is a nice little skit of the usual sort, and it leads, rather inevitably, to Larkin and general worrying “that England will be gone.” The trouble is, it’s pure banana oil, as P.G.W. would say. What Dyer regrets as “the very idea of a national rail system” was in fact the problem.

Writing essays can be an easy way to avoid thinking about problems like this. It’s quite legitimate for Dyer to carp his mid-century nostalgia and carry on, as if passenger numbers didn’t decline under British Rail and then recover under privatisation. He’s under no obligation to tell you that passenger satisfaction in the UK is often higher than in France and Germany, that journeys increased massively under privatisation, that the average fare increases were lower than under British Rail for the first fifteen years of privatisation. Nor does he have to mention that UK trains are some of the safest, and that investment rose after privatisation.

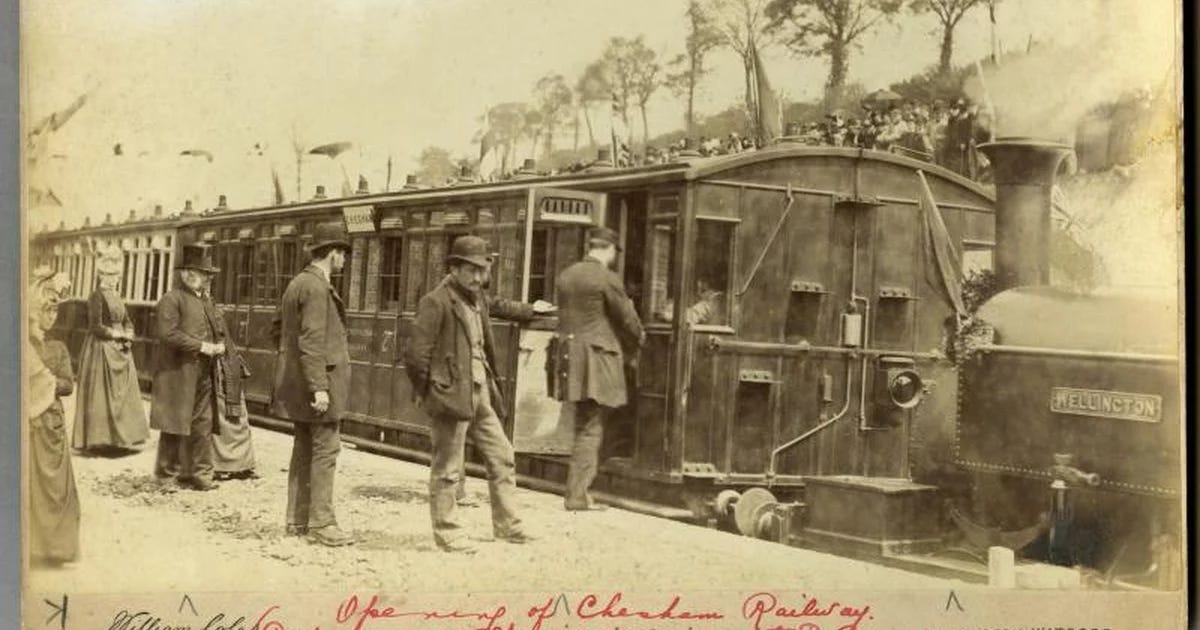

No, facts are not obligatory in essays. But they do help. And Dyer’s style of musing suffers for the lack of them. Nostalgia is only persuasive to the people who share your taste for British Rail as opposed to the late-Victorian system of many independent companies. If you want real railway nostalgia you need to do better than a bit of half-hearted whimpering for what was, even by the standards of nationalised British industries, a horrible under-performer. Margaret Thatcher was opposed to the railway privatisation, causing her advisor Ferdinand Mount to ask whether that wasn’t exactly what Thatcherism was supposed to be, restoring competition and all the traditional liveries of the individual lines. Nostalgia can cut both ways.

This isn’t to say that there aren’t problems with the franchising system, which the government is now looking to reform. But one way of thinking about this issue is that when there are government restrictions on what routes train companies are allowed to run and regulatory restrictions on the fares they are allowed to charge, the railway is never fully privatised. (According to the House of Commons Library: “About 45% of rail fares, including season tickets and commuter fares, are regulated fares.”) The reason there isn’t more competition on the train lines, as you would expect from a privatised industry, is that government doesn’t allow it. The trend, by the way, has been towards fewer, more restrictive, franchises.

The Dyer argument — and it is a common view, even most Tory voters want to nationalise — cannot even grasp the distinction between competing for the market and competing in the market. The train system allows the former, not the latter. Once you have your franchise, you are running a government-regulated monopoly business. And for a privatised business, it costs the government a hell of a lot of money: “In the admittedly difficult circumstances of the financial year 2020-21, the Department for Transport spent £26.4 billion on rail, a 46% increase on the previous year.” Did I mention that delays are often the fault of the tracks, not the trains? The tracks, of course, are owned and maintained by National Rail, a government body.

Why is it that Dyer couldn’t have told us some of that? What is this obsession among the literary to rely more heavily on Philip Larkin than on the reports of the House of Commons Library?

In his review, Kuper says this:

Then there’s the decline in technique. Dyer admits that his own ability to recreate scenes with lyricism and romance “has diminished, disintegrated” with time. But that ability is most of writing.

O Lord give me the serenity to accept what I cannot change. Lyricism and romance are not “most of writing”. Good writing is specific. “Proper words in proper place make the true definition of a style.” (Why did we stop making children memorise that sentence?) And what are proper words if not factual? If Kuper and Dyer want lyricism and romance they have the whole gamut of literature from Chaucer to Barbara Cartland to keep them happy. The common reader deserves more, from its reviewers as well as its writers.

Kuper also quotes this, from Dyer:

A condition of being able to go on creating late into one’s life seems often to be an inability to see what, for readers, is the most distinct quality of this later work: its deterioration in quality.

This, of course, is not necessarily true. It isn’t true of Michaelangelo, Penelope Fitzgerald, Frank Lloyd Wright, Edward Jenner, Sister Wendy Beckett, Yitang Zhang, Anton Bruckner, Vera Wang, Edward VII, Paolo Uccello, Margaret Thatcher, Samuel Johnson, Anne Clough, Seneca, or Beethoven. If you want to know more about people who do some of their best work later in life, I will have a book recommendation for you one day…

Sorry for the rant. Normal service will resume next week.

The Last Days of Roger Federer

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

I enjoyed this, thank you!