The Last Jubilee? Long live the Queen...

Does the age of chivalry belong in the past?

I wrote for The Critic this week about whether this will be the last jubilee. This essay has some additional information and history about that argument.

As Nicola Shulman points out in her review of Tina Brown’s new book, drama is poison to the monarchy and the Harry and Megan situation means the royal family now has a case of Long Diana. Drama is the problem that won’t go away.

There has long been a remedy for this sort of bad press: royal events. The basic function of royalty is to be respectable in private and to have glittering weddings, funerals, christenings, and jubilees in public. Stability and spectacle are the twin pillars of the Queen’s success.

We are used to these events being well-orchestrated, brought off with the timing and aplomb of the Royal Ballet. It was not always like this. The process has been well refined over the last two hundred years.

In 1817, the pall bearers at Princess Charlotte’s funeral (who, had she lived, would have been queen instead of Victoria) were drunk. The national anthem wasn’t sung at Victoria’s coronation in 1838. The rest of the ceremony was no better. The clergy lost their place in the order of service and two train bearers talked throughout. Royal weddings have been a sure thing since the 1863 marriage of the future Edward VII to Princess Alexandra. But between 1861 and 1886, despite numerous royal weddings (all those imperial children), no commemorative pottery was produced. In 1864 some wag put a sign on the railings of Buckingham Palace, ‘These commanding premises to be let or sold, in consequence of the late occupant’s declining business.’ In the 1870s republican clubs were formed across the country.

This all reversed in the last decades of the nineteenth century. Although Victoria was withdrawn from politics (hardly even opening Parliament) her jubilees and diaries meant she was able to become a popular monarch. The newly urban population who read newspapers like the Daily Mail (and with advances in photography and printing saw more of their news) lapped it up. In an age of machines, mechanised transport, and telegrams, the nostalgia value of Royal coaches and costumes began to rise. Princes of Wales started going on royal tours to imperial domains like Canada and India. Edward VII’s coronation in 1902 was a stark contrast to Victoria’s. One commentator wrote, ‘The archaic traditions of the Middle Ages were enlarged in their scope so as to include the modern splendour of a mighty empire.’ Edward VII was also the first monarch to lie in state in 1910.

As David Cannadine says in The British Monarchy c. 1820 – 1977, the monarchy replaced power with performance. The reign of George V (1910-1936) represented the final stage of the creation of a new tradition for British Royalty. The covenant of the royals and their public was elevated to ‘private probity, public spectacle.’

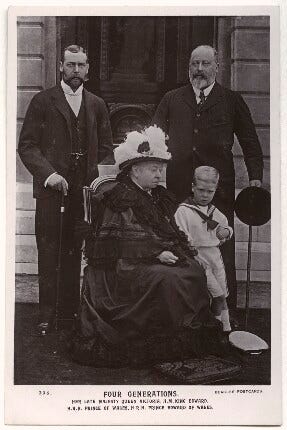

We are reaching a pinnacle in that tradition. Perhaps we’re already over it. Not since Queen Victoria posed for a photograph with her son, grandson, and great-grandson, has the line of succession been so secure. What better way to proclaim the stability of your performative power? And Victoria never made it to her Platinum Jubilee. But within that picture there lurked a portent as well as a proclamation. The baby, the great-grandson, was the future Edward VIII — the Abdicator. Are we more confident than they should have been?

It was ever thus, of course. After the constant fretting about the Tudor succession, James I, the first Stuart king, was careful to show off his family, the Royal family, to make the stability of the kingdom plain for all to see. He had heirs and spares aplenty. But that didn’t prevent the gunpowder plot. Quite the opposite. And his son, Charles I, lost the crown altogether. The same thing happened with George III and his sons — they were useless, womanizing, drunks to a man, known to history as Victoria’s ‘wicked uncles’. Stability breeds instability. It encourages complacency, maybe even hubris.

The throne has been lost before. Why not again? Andrew is a perpetually ticking bomb that cannot be defused. In the age of celebrity royalty, Harry and Meghan are the Sussexes across the water. And the intense PR operations of the various royal houses are only a blessing when — and if — they work in harmony. Without the Queen’s influence, who knows what cultural clash will play out between the generations. Private Eye reported that Charles wore his Admiral’s uniform to upstage Prince William at the recent opening of Parliament, having agreed to wear suits with William beforehand. Hardly a good auspices.

And then there’s the media. It’s not fair to put too much of the blame for the Diana debacle on the royal family. The press didn’t have to hound a young and vulnerable woman the way they did. When pictures of Diana wearing a bikini while pregnant were published, the Queen was furious. She summoned editors to Buckingham Palace and told them to leave the poor girl alone. Alas, we all know what happened. As royalty increasingly becomes a form of celebrity, press incursion will be no less of a risk to the firm and the values they are supposed to represent.

These risks are heightened because this is going to be the last jubilee for some time. A major part of the Windsor appeal — the magic that props the succession up — is splendid spectacle. Gold carriages, Red Arrows, and white horses are all integral to the continued existence of royalty in the UK. Once this jubilee is over, though, the opportunities for spectacle are fewer and further between.

We’ll have Charles’ coronation and William’s investiture… and then a long period without much glitter and glamour and plenty of opportunities for drama. Perhaps when it comes to stability, the royal family has done too much of a good job. What exactly is delaying that memoir of Harry’s? It will either be damaging for what it does contain or for what we will speculate he left out. Are there any good scenarios for a living royal writing a book that isn’t a Queen Victoria-style diary?

And we haven’t yet mentioned the fact that the Queen is a queen. When she came to the throne she was young and fair, a vision of hope and renewal for post-war Britain. ‘Let it not be thought’, Churchill could say of the Queen’s coronation, ‘that the age of chivalry belongs in the past.’

She was so different from the grey old men who had gone before — and from the grey men who are coming next. There is something mythical about British queens. Churchill said when the queen’s father died:

I, whose youth was passed in the august, unchallenged and tranquil glories of the Victorian era, may well feel a thrill in invoking once more the prayer and the anthem, “God save the Queen!”

Can you imagine such optimistic rhetoric when Charles is crowned? Elizabeth II always looks regal. The men often look more like they run a golf club.

The Queen has always lived up to that Churchillian ideal. She is chivalrous. She is gracious. And noble and glorious. Or at least, we believe she is. She leaves only the smallest gap between herself and her public persona. She really did marry private probity with public spectacle. When she appears in her robes and feathers we are charmed not just by the spectacle but by the quiet, steady, well-behaved woman in the crown. She is the last hope of a dying ideal. How can Charles and William follow her?

In some sense, monarchy has not yet been tested by full-franchise post-war democracy. The Queen is an outlier. What if the magic she created was her magic? It is no guarantee that what we feel for her we will feel for the others. Prince Charles, you know, is only the sixth most popular royal. As my father-in-law once said, ‘I’d lay down my life for the Queen, but I’m not sure about the rest of them.’

Because of the Queen, we’re so used to the idea that royal pomp and circumstance was a reliably good deed in a naughty world. As I asked in The Critic, are we sleepwalking into this being not only the last royal jubilee for a long time, but the last one ever?

My next salon is TONIGHT Tuesday 31st May at 19:00 UK time. Is what makes the Life of Johnson great the subject Samuel Johnson, pioneering lexicographer, poet, essayist, pillar of morality, and Latin scholar—or the author James Boswell, failed lawyer, frequenter of prostitutes, sycophant, and a drunk?

Book a ticket to join the salon.

Tours of London

New dates for my tours of London have been released.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

Very interesting thank you. I can't bear to see the horses though. We do not ride them into battle any more. We do not need them as a show of military might.

Thousands of them taught to suppress their fear, surrounded by screaming people, saliva pouring out of these mouths, being ridden by large humans in full uniform, banging drums on each side of the horses' body and their metal horseshoes slipping on the cobbles making them struggle even to walk.

The horses must be put out to pasture. Personally I think when the Queen goes, the royal family too.

Jo