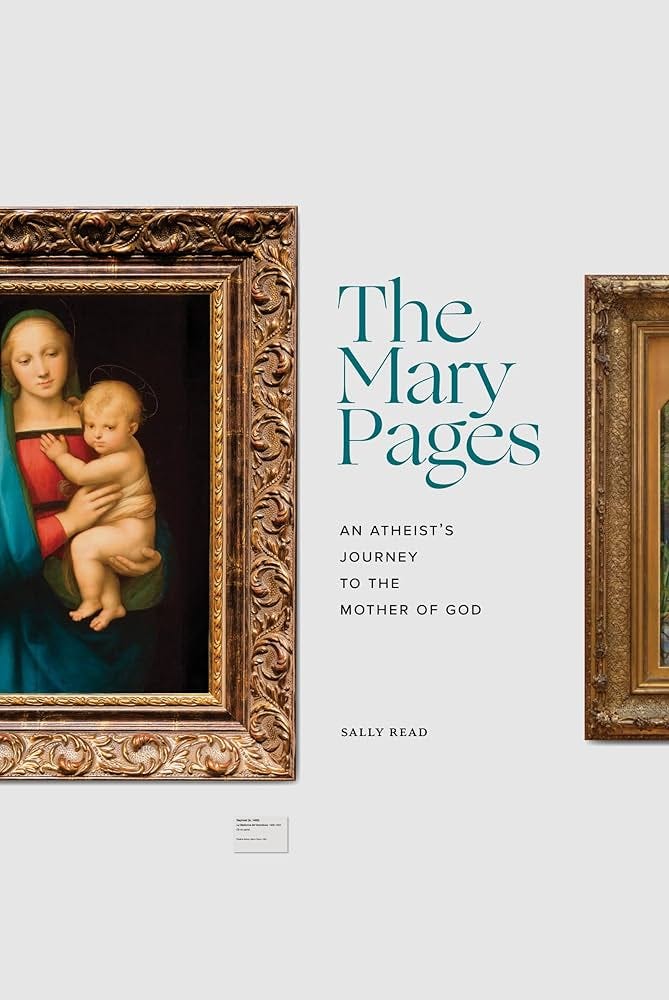

The Mary Pages, by Sally Read

An Atheist's Journey to the Mother of God

This is the new memoir from the poet Sally Read. I enjoy Read’s poetry and was very pleased to read this. Here is a good religious poem. And here is a collection based on her time as a psychiatric nurse.

The Mary Pages tells the story of Read’s obsession with the Virgin, from her atheistic childhood to her conversion she has always looked intently at the various depictions of Mary and thought about them as reference points for cultural, spiritual, and political matters. As well as being a good memoir, The Mary Pages is full of art interpretation, religious thinking, discussions of relationships, motherhood, marriage, and so on, but in an entirely different way to the norm.

There are other naked Madonnas: Edvard Munch painted the Virgin exposed in sexual ecstasy with a red halo. But he, like all the others, misunderstood the sublimity of her form. I see indifference in the eyes of Munch’s Madonna, and contempt. The quiddity of true love and ecstasy (the perfect blend of eros into agape) is clear and arrow-like; it only illuminates. When the substance of pure love is interpreted by the disillusioned, the sad, the hungry, the angry (i.e., most of us), it warps into power games, shame, and hurt. She is powerful, the feminists might say of Munch’s Madonna. I say, better to keep her clothes on.

The fact is that no one is ready to see Mary dance naked at the dawn of time. For us, dancing and nakedness segue quickly into the erotic, and the doors open to the stampeding dopamine hits, the snowballing fantasies of concupiscence and pornography. Which means that we are incapable of thinking of the Virgin dancing; we are incapable of thinking of her naked. We are stooped and narrow-sighted as Adam and Eve lurching out of the Garden.

And this.

By now, I was used to the ordinary theater of the Church (not the sacrifice of the Mass, which was the epitome of lucent understatement, as though the atom were split at the altar each day and we simply crossed ourselves and bowed our heads). I mean the theater of the tiny skull of St. Agnes in Rome, which we took our visitors to see. I mean the black tongue of St. Anthony in Padua. Or the incorrupt body of a blessed nun that lay in a glass coffin in a chapel near our house. I mean the one silver hair belonging to the head of Pope St. John Paul II that was twisted artfully around silver pins to form a flower and given to a friend. The night I was received into the Church, I was passed that saint’s rosary by his housekeeper and held it in my hands. I played with a fragment of St. Bernadette’s habit and a clump of soil from the grave of St. Rafqa. Even Mary’s veil is supposedly preserved in a church in France. I had looked at its image and wondered if it had really touched her head, if her eyes had studied with pleasure its pale weave of stripes.

“It’s a death cult,” my New Yorker friend Maisie said of the Church, and I agreed that attachment to bodies, and things of the dead, was strange. But as a young woman, had I not gasped at the drafts of Sylvia Plath’s poems in the British Library, the red-inked flower she doodled under a poem? I thought I could see her movement, her life, in each stroke—like the dried pulse of spilled blood on La Madonnina’s plaster cheek. (And when I walked into a hospital office a year after splitting with Mischa and saw a note in his handwriting on a file, didn’t I jump violently as if it were a coiled snake?)

Here is a passage from a section where Read discusses Mary’s devotion to her son. The Mary Pages is probably not the book many people want to read about motherhood, but I found it interesting, forthright, honest, and well-expressed.

“My soul magnifies the Lord,” Mary sang at the accomplishment of what she was made to be. It’s clear to me now that in her whole and jubilant womanhood, she would never want to be separated from him. And for those who say Mary is sexless, I say: think of to whom she gives her sexuality and of what else she gives him (her everything); think of how she yielded in her extraordinary conception, of how she loves. In her, there is no division, no rupture, no forgetting of what she is, no self-hatred. There is no falsity, no playacting, no confusion, no withholding from her Maker. She is as responsive as the sea to light and cloud, as generous as air that endlessly expands, as ecstatic as a bride and as faithful. I believe she loves her naked body and is at ease with her breasts and her rounded belly, because he does, and because he is.

Of course she knelt before him.

For what mother, I ask de Beauvoir twenty years after that blizzard, does not kneel before her baby? What mother has not knelt before the crib and felt something like the wordless and surging adoration of prayer? A mother’s love for her baby is overwhelming. It crescendos in waves. It comes like labor pains: just as she thinks that she can take no more, the intensity disperses, leaving her gasping. God knows that we can’t hold the entirety of love (or pain) in one go. It would tear us to pieces. But mothers have a privileged glimpse of this infinite love that binds us so thoroughly to our children. When we kneel before our child, we are bowing at a glimpse of divine love that effortlessly holds everything.

I love Munch’s Madonna tho

Looks very interesting. How did you end up picking this one up?