The secret to being a great writer

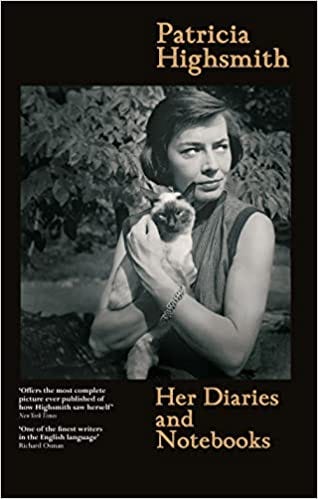

Patricia Highsmith's Diaries and Notebooks

My salon about The Tortoise and the Hare — one of the great post-war English novels — is on February 1st. We’ll be discussing the novel and the real life story behind it. I’d love to see you there. (And if you haven’t, do read the novel.)

It is not the least of her achievements that, alongside drinking like a Raymond Chandler character, running through relationships as if they were cigarettes, often sleeping for only three or four hours, sitting in bars all night, staying up to write her journal well past midnight, and slogging it out in a hateful job, Patricia Highsmith managed to write a book at all. The fact that she had one of the great literary careers of the twentieth century is astonishing.

“Your writing is improving marvellously,” her mother told her while she was trying to write her first novel, “but despite your life, not because of it.” The secret to her productivity, which is the perpetual mystery with writers, can be found in her Diaries and Notebooks (US link). Anyone who thinks, as Highsmith said, “If only I’d known how to write a book before I started!” will benefit from them. (Although the book is very long: it is a fraction of the manuscript, but it could have borne more cutting.)

Modern productivity advice has no place here. To make any comparison between Highsmith and the view of productivity that advocates clean living, self care, sleep hygiene, meditation, yoga, healthy diets, early rising, gratitude, temperance, and all the rest of it, would be laughable. Not laughable in a rhetorical “it isn’t worth the candle” sense: I really do think she would laugh, rather cruelly perhaps, at that advice. She is concerned with great art. These diaries are a record of the pursuit of genius. And to high art, there are no shortcuts.

The first thing you need to do if you want to be a great writer is to read. Highsmith read intensively. Not just volume, but depth, and only of the first quality. Proust is never far away. She travels with him often. Dostoyevsky is her master. “He helps me a great deal— with his exclamation marks, his confusions!” She considered Dostoyevsky to be a suspense writer, along with Henry James. She is not a genre writer: she is working in a tradition that joins Dostoyevsky with Wilkie Collins, Henry James with Edgar Allan Poe. Like all great writers, she is an original. “I have my art, and my art alone is true.”

That brings us to motivation. Once you have read and read and read and know you want to write, you need to know why. Her answer is deceptively simple. “It is not conscience that prompts me to write, because I am a writer it is only dissatisfaction with this world.” Dissatisfaction comes in many forms. She is the classic writer at odds with herself and the world. “What is it, underlying all, that creates dissatisfaction? The young person’s fear that he is (basically) not on the right track, his own track, that all may have to be scrapped, the way retraced.”

She was also pretty grumpy about capitalism, lovers who weren’t intellectually stimulating enough were dropped like hot bricks, and she found her job a complete drag. “Where are their moments of reality” she asked of office workers, unable to contemplate their oppressive tedium and fatigue, “at the breakfast table, in bed with their wives? Gardening? Washing their cars? Or are they another species of animal that does not need reality?”

Once you’ve done a lifetime’s reading by your early twenties and discovered your innate artist’s misanthropy, you need technique. Not just “proper words in proper places” technique, but actual nuts-and-bolts where-and-how-to-write technique. She disliked her typewriter because it demanded her obedience like literally nothing else could: “The typewriter is above all alert, sensitive as you are, far more efficient in its tasks. After all, it slept better than you did.”

This passage might be more honest, and more useful to the aspiring artist.

I do everything possible to avoid a sense of discipline. I write on my bed (bed made up, myself fully but not decently clothed), having once surrounded myself with ashtray, cigarettes, matches, a hot or warm cup of coffee, a stale part of a doughnut and saucer with sugar to dip it in after dunking. My position is as near the fetal as possible, still permitting writing. A womb of my own.

Maya Angelou was similar, only she had a bottle of sherry and a Bible on the bed. Patricia also needed music. Bach is a constant companion. (Tocata, Adagio and Fugue BVW 564 and Piano concerto in F minor BWV 1056 get special mention.)1 In one particularly enjoyable passage, when she is “drunk on three cups of coffee”, struggling to work on a snowy morning, tempted to read Henry James all day, “the radio plays bassoon sonatas.” Music, like the womb of her own, is a sign of her necessary isolation. She said in a late interview, “I choose to live alone because my imagination functions better when I don't have to speak with people.”

Most writers leave nothing so useful behind in their diaries as actual “proper words in proper places” advice. Highsmith is much more obliging. This passage deserves to be quoted in full. Anyone who wants to write anything has to learn this at some point.

Write as a painter paints, with renewed awareness of the work of choosing and rejecting. Remember (and realize) that a sentence may be set into the middle of a previously written paragraph, without interfering with rhythm, that this sentence can be the iron bolt, or the germ cell, or the life itself, all added later, as the fleck of white at the end of a nose may quicken the entire portrait. Apply sentences like strokes of color. Survey the work as a whole from time to time and experience it as though it were a painting. This shift in itself provides a measure of poetry, the necessary untruth of art. Scenes are necessarily separate pictures, but the experience of the whole should be orgasmic, productive of the wordless joy and satisfaction one feels looking at Van Gogh’s “Night Café” or at Marsden Hartley’s workman’s shoes.

Choosing and rejecting is important for more than sentences and paragraphs. Highsmith threw out two novels before she started Strangers on a Train, her first published novel that became a global bestseller and was made into a movie by Alfred Hitchcock. She had the idea in 1945, when it gets a passing mention. “Thinking of a novel based on my idea of two soul mates.” She then got quite some way into one of the abandoned novels. The book was published five years later.

It was worth waiting. “I just want a strong, clear idea.” Well, she got one. She wrote later that it’s useless asking writers where their ideas come from. She described them like birds in her peripheral vision, which she had to choose whether to bring into focus. All the technique in the great wide world can’t teach you that.

It’s about more than ideas, though. Writing Strangers took a hell of a lot of work, and eventually, with letters of recommendation from Truman Capote, she went to the Yaddo writers’ retreat to finish it. It’s more than a murder plot. It’s a submerged lesbian story, full of erotic tension, that was ironically inspired by her sessions with a psychiatrist about her homosexuality. It is also about a split self, a nebulous, worrisome identity. That is the final thing you need in order to be as good a writer as Patricia Highsmith. That and a drinking problem. The two inevitably, and rather sadly, go together.

Hence the diary is full of this sort of aphorism. “A little liquor is necessary to enable one to rediscover one’s self. The self is a constructive and real being. The modern world is not.” Think that doesn’t sound so bad? It gets worse. “The tragic desperation the first drink represents… the one taken at three in the afternoon. For one seeks peace of mind, and this drink is not the first resort, but the last. There is before it all the long chain of effort for silence, tranquility, love, faith that has somehow failed.” She wrote that when she was twenty-five! She sounds like Philip Larkin in his sixties. Even at Yaddo, with its early-to-bed, clean living policies, she was sipping rye and water in the morning, “to reduce my energy from 115% to 100%.”

For years before she cracked it, she was thinking about the basic idea of Strangers. “What to do with homosexuality?” she asked herself in 1942, unable to write an openly lesbian novel. “The transformation of the material is utterly impossible — unless one changes the characters to be abnormally inhibited.” She solved that problem with real genius and went on to write the first lesbian novel with a happy ending. But it’s about her, not just her theme. You cannot separate the dancer from the dance; however well done it is, however transmogrified, whatever level of genius recreates the novel out of the writer, she remains. “I am troubled by a sense of being several people (nobody you know). Should not be at all surprised if I become a dangerous schizophrene in my middle years. I write this very seriously.” She was troubled by the gap between her inner and her outer self: deeply enough to write novels like The Talented Mr Ripley. Here she is sounding rather a lot like Ripley, years before he’s even a bird in her peripheral vision.

I prefer to be romantic. I want the strand of hair, the desperately opened, desperately guarded letter, the scuff on my shoes I will not shine off, the telephone call that means life or death, the sweet pain that comes when the one you love has done you the simplest kind of favor… I want the end to be a fall deeper than from Mount Everest so that it will terrify me, as I watch the whole world fall with me.

The real secret then, to being Patricia Highsmith, is to be Patricia Highsmith. You cannot replicate these tricks and expect the same results. Not just because you don’t have her stomach for alcohol (believe me, you don’t) or because stale donuts aren’t your thing. Because you lack her sense that, “The place is here, the time is now.” Above all the misery and disease in her character, there was an inborn, monkish dedication to art.

“There is no secret of success in writing,” she wrote in her primer Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, “except individuality.” Her advice is simple. Be yourself. Use the “maximum of one’s talents.” If you aren’t a great artist, you’ll find out. And if you lack ideas, she recommends a holiday, to get away from the day job. If you can’t afford it, take a walk.

In the end, all the advice, all the techniques, all the productivity routines — all come down to this. “I have been forcing myself to write for an hour a day for years.” All you have to do is pay attention to the world and write about it. “A writer should not think himself a different kind of person from any other… He has developed a certain part of himself which is contained in every man: the seeing, the setting down.” As she said, “It is endurance that counts.”

So that’s how you write great literature. You school yourself to breaking point and then you tap your soul the way you might tap a tree to get syrup. It happens two ways. First very slowly; then very fast. Strangers was drafted in six weeks at Yaddo, after all those years of labouring. Rather wonderfully, Highsmith made Yaddo the beneficiary of her estate and all future royalties.

Related Common Reader essays

Do Writers Have to Write Every Day?

Do Real Artists Write Schlock?

Oddly-angled observation. The Sin Eater, by Alice Thomas Ellis

How J.A. Baker became a great writer after showing no signs of talent for forty years

Syntax is the Secret to Good Writing

Book links

Patricia Highsmith Diaries and Notebooks (US link)

The Talented Mr Ripley (US link)

Strangers on a Train (US link)

Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction (US link)

Don’t forget to book your ticket to the salon about The Tortoise and the Hare — one of the great post-war English novels — on February 1st. We’ll be discussing the novel and the real life story behind it. I’d love to see you there. (And if you haven’t, do read the novel.)

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment at the bottom.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up now.

For Bach and organ lovers who live in London, St Paul’s is running free thirty-minute recitals every Sunday at 16.30.

Which PH novel would you recommend for starters? Strangers?