stylish defiance

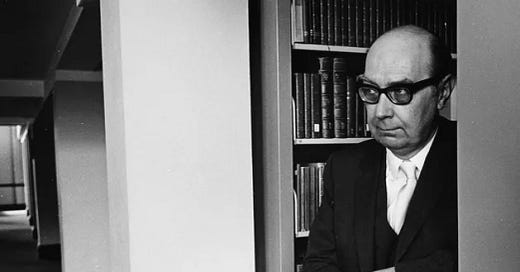

Dana Gioia’s new book of essays about poetry covers much interesting ground, from his Longinian essay about poetry as enchantment to his lively biographical pen-portrait of Donald Davie to several shorter pieces about particular poets, including Philip Larkin. Nominally, Gioia’s essay is a review of James Booth’s (splendid) biography of Larkin (which aimed to save Larkin from the degraded position his literary executors had condemned him to by presenting him, in a selection of letters and a biography, as little more than a miserable, racist, hateful man), but it becomes a full blooded essay in its own right, which aims to restore some balance to Larkin’s reputation, just as Booth’s biography had done.

The Selected Letters first revealed Larkin’s horrid side. And his natural exuberance in those letters only exacerbated the problem. As Gioia writes:

That the letters, so full of gross obscenity and invective, were also pithy and entertaining, only made matters worse. The great bard suddenly became the great bastard.

I read Larkin’s letters nearly twenty years ago in a sun-filled room in a village where elderly residents still remembered the old baker who got up late, cycled into town to place bets on the horses, and baked the bread in the afternoon. Fresh loaves were delivered in after supper. As the quiet summer turned in the field outside, I was gripped for several days as the Selected Letters followed the rising of a talent and the collapsing of a man. Like the life of the village and the wheat of the field, Larkin rose in vigour, flowered in a light almost too intense, and fell to the mud, broken and empty.

To those who felt that modernism had been, if not a mistake, then too much of a turning away from the tradition, Larkin was a pinnacle of resistance. True, he found the Georgians disappointing when he edited his anthology of twentieth century poetry. True, his moments of hilarious poise, such as when he asked the Paris Review who Jorge Louis Borges was, seemed to tip over into (drunken?) belligerence. True, he was sometimes a reactionary not only in aesthetics but politics too. But who else put up such a show in the face of a changing world? Who else had, to borrow the phrase Adam Kirsch used to describe the attitude that highbrow culture ought to take in its new role as the counter-culture of the twenty-first century, that certain stylish defiance?

If T.S Eliot has the sprawling genius of a near-mad, romantic, depressive scholar, Larkin has the neat elegance of an English pessimist. Where Eliot wrote long verses about “the intolerable wrestle / With words and meanings”, Larkin cynically shrugged: “but why put it into words?” Eliot is sometimes claimed as a quotidian poet, a writer of ordinary lives, but he never came close to Larkin describing what it felt like for the ordinary person to go up to see a “faith healer”, clasp their hands for their prayer, and then find themselves “exiled/ Like losing thoughts, they go in silence.” For all his wishes to have been able to write more like the French symbolists, Larkin is often most poetic when most prosaic: “You can’t put off being young until you retire.” Many poets have written about the moon and about youth and age: none has quite matched the plain sadness of these lines:

One shivers slightly, looking up there.

The hardness and the brightness and the plain

Far-reaching singleness of that wide stareIs a reminder of the strength and pain

Of being young; that it can’t come again,

But is for others undiminished somewhere.

That is exactly what Larkin’s letters capture so well: they are “a reminder of the strength and pain/ Of being young; that it can’t come again.”

the true voice of feeling

In his early days, Larkin is simply irrepressible. When the keys on his typewriter get stuck mid-letter to Kingsley Amis he lets off a reel of strong language.

FUCK THIS ARSEHOLING TYPEWRITER WHATS THE MATTER WITH THE SODDING THING????"

Writing to Amis in middle age some decades later, this fury recurs.

Being in the unusual position of knowing what was on the wireless tonight I switched on for your Kaleidoscope thing and got ten minutes of fuckfuckfuck longhair crap (this typewriter does that quite often) before hearing you weren’t going to be talked about. Shit to that.

Larkin, in his letters, is vivacious, adjuring, impertinent, comedic, plangent, rude. Though crass, he often writes with more energy than his words can contain. Famous for writing, of young mothers that “Something is pushing them/ To the side of their own lives”, in his young letters, Larkin often feels like his frustrations and angers and urgings cannot be kept within the bounds of his existence: pushed to the side of life himself, Larkin rises up from his ordinary prose to dog-like gnashing and wailing. As he aged, and remembered the strength and pain of being young, this became uglier and uglier. Samuel Johnson once said that men make beasts of themselves to relieve the pain of being a man, but one never gets the sense in Larkin’s letters that the relief was anodyne enough.

Despite all that, he is funny. Here’s what he wrote to Amis about the Oxford English syllabus. (Amis did a short degree because of his war service.)

Sorry I haven’t written for some time, but I have been snowed up with fucking work. Kingsley my dear boy thank God you didn’t read full schools. You have to learn two things about each poet — the ‘wrong’ attitude and the ‘right’ attitude. For instance, the ‘wrong’ attitude to Dryden is that he is a boring clod with no idea of poetry, and the ‘right’ one that he is a ‘consummate stylist’ with subtle, brilliant, masculine, etcetera etcetera. Irrespective of what you personally feel about Dryden these two attitudes must be learnt, so that you can refute one and bolster up the other. It just makes me crap.

Larkin’s laughs are often combative. This brawling temperament is something Larkin shared with Keats, even though their letters are as different as different can be in many ways. Pugnacious both, their poetry shares a sense of mourning for the world as they thought it would have been, and a sense, too, that they never quite captured their youth. Look again at Keats’ sonnet ‘When I have fears that I may cease to be’, and think about just how Larkinian it is. The more you look at ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ (‘The weariness, the fever, and the fret/ Here, where men sit and hear each other groan’) the more you see that Larkin didn’t merely borrow Keats’s stanza structure for ‘The Whitsun Weddings’, but revitalised his whole sensibility of lively melancholy.

We passed them, grinning and pomaded, girls

In parodies of fashion, heels and veils,

All posed irresolutely, watching us go,As if out on the end of an event

Waving goodbye

Surely we are back in Keats’s reverie

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs,

Where Beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes,

Or new Love pine at them beyond to-morrow.

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow—those two impatient souls shared a temperament, an obsession with what Larkin called “the solving emptiness that lies just under all we do.”

on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.

Keats, or Larkin? In a game of “who said it” the line “That I might drink, and leave the world unseen” would surely give us pause. Because, year by solitary year, alone and dedicated to his shrinking art, Larkin became a drinker who did, while he was alive, leave the world unseen as much as he could, refusing even to appear before the camera in one documentary about his life and work. Keats’s great line “To thy high requiem become a sod” is nothing like Larkin in its diction, but is everything like him in its gloomy, prognosticatory tone. What could stand as a better epigram to his work?

It would be a mistake to push this comparison too far, but a brawling Keatsian humour is both the essence of Larkin’s work and what he is constantly reacting against. They both wrote with what Keats called “the true voice of feeling.” Larkin is Keats become middle-aged, living with thwarted expectations, re-performing what was once the strength and pain (and humour) of being young as the sharp misanthropy of being old.

Aware of his Romantic heritage, Larkin famously said that misery was to him what daffodils were to Wordsworth. There’s to this comparison than a joke. As Christopher Ricks said, Larkin’s poems have “a Wordsworthian core, an ordinary sorrow of man’s life, here in the world of all of us.”

smaller and clearer as the years go by

But Larkin was a genius: misery was not enough. The caricature of a lonely, embittered man, racist, sexist, misanthropic is all quite true; he was dreadful; but Larkin was more than this: poetry was his access to something better and more permanent. Whatever feats of pessimistic chauvinism he achieved personally (by the end he was refusing invitations and drinking sherry at breakfast, plump as a seal and cheerful as a vulture), he turned himself to poetry, to the vigorous melancholy of verse. The letters chart with such morbid intensity Larkin’s turn into a suburban King Lear, pathetic as well as pitiful. As he aged, Larkin was gummed up. Where the typewriter keys had been jammed in youth because of his enthusiasm, his energetic opposition to what had come before, his hard certainty about the importance of art, now he was merely swollen with belching anger. James Booth’s splendidly corrective biography hasn’t quite cleaned off the patia of unglamour. Nothing ever will. He was grim.

Despite all this, we like to quote Larkin sentimentally: what will survive of us is love. But that isn’t what he meant at all. Look at the preceding lines: he calls it an “almost instinct” and “almost true”. ‘An Arundel Tomb’ is not a devotional lyric but an ekphrasis. He was writing about history and how we interpret the past. What survived of Larkin wasn’t love. Not at all. But it wasn’t only melancholia either: it was hope, resistance, sceptical curiosity, and the instinct to preserve life in art. If he feels small and parochial and mean now, remember that he once said photographs made their subjects “smaller and clearer and the years go by”—and that photograph are not real. In snapshot, in letters, Larkin can seem more taut and tormented than he was.

In his poetry he was capable of more. He once told an interviewer he wanted to be able to write more poems like ‘First Sight’, which describes the early lives of lambs. I prefer to think of him in the middle of his life, held in tension between his young energy and the creeping light of the deathly dawn he so bleakly described in ‘Aubade’. His greatest resistance to modernism wasn’t in his philistine posturing or his rhymes, but in his near symbolic, near optimistic, neo-Romantic description of that very ordinary thing, a train pulling in to a London terminus.

There we were aimed. And as we raced across

Bright knots of rail

Past standing Pullmans, walls of blackened moss

Came close, and it was nearly done, this frail

Travelling coincidence; and what it held

Stood ready to be loosed with all the power

That being changed can give. We slowed again,

And as the tightened brakes took hold, there swelled

A sense of falling, like an arrow-shower

Sent out of sight, somewhere becoming rain.

This is not the Larkin of the Selected Letters, not the Larkin of misanthropy, misogyny, bigotry, and racism. In the letters, he often seems more interested in pornography and crass remarks than in the power that being changed can give. Indeed, the main power of change in the letters comes from the gravity of despair, that drags all life into a creased and saggy misery by the book’s end. In ‘For Sidney Bechet’, Larkin wrote that once Bechet’s music starts “in all ears appropriate falsehood wakes”—but for many, it was not an appropriate falsehood that they found in Larkin. No matter that the remarks he made were so often, as Dana Gioia points out, meant to be jokes. (Larkin said in an early letter to Amis: “NB This is not serious — do you catch the note of hysteria.” Many did not catch that note.) These jokes were in bad taste, often in very bad taste, and were very much an inappropriate falsehood. And the compelling tragedy of the letters is that they do stop being jokes. The intolerant despair of the poetry had been acceptable; this was not—is not.

So there were two reactionaries in Larkin: both studied, both to some extent genuine, both unbending, in their way; but one was the reaction of music and poetry, while the other was the reaction not of foot tapping but of sour scowls, not of clever rhymes but hateful language. Not, as Gioia points out, that it is always so simple to distinguish between the two:

When the young librarian wrote his parents, “Children I would willingly bayonet by the score,” he was not planning a serial killing. The man who told a reporter, “Deprivation is for me what daffodils were to Wordsworth” was a habitual performer and ironist. All his life Larkin remained in some sense a goofy adolescent desperately trying to impress his friends by saying outrageous things— not just about sex, women, and minorities but about religion, art, marriage, friends, family, America, and especially his fellow poets. One need not exonerate him, but one should at least try to understand him.

Need I say that, as a young admirer of Larkin, I was an aesthetic reactionary, not a political one? I watched in wide-eyed-terror as the young man who twirled his imagination to the rhythms of jazz became the old bastard who scorned people of colour. As I drove fast along Dorset lanes with “Maple Leaf Rag” and “Shag” swinging hard, all windows down, all sense of being in a hurry gone, I felt the ready to be loosed into the summer air, and Larkin’s words were full of life in my mind “Oh, play that thing!”— how irreconcilable that Larkin is with the Larkin of the late, hateful, letters.

I was (back then) sympathetic to his aversion to modernism and its descendents. Aged fifteen I walked out of the Sagrada Familia, appalled that anyone could consider that to be architecture. I told my family I’d be at the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, a magnificent gothic building of the fourteenth century. I simply couldn’t take it for another minute in that dreadful place. (In my mind I still often visit the garden of Saint Eulalia, with the palm trees, geese, and mossy stone fountain.)

Larkin was no admirer of the old for its own sake: he had no interest in poems about myths. But he was one of those who visited churches, a “ruin-bibber”, “randy for antique”. What I didn’t fully appreciate then was just how nihilistic Larkin could be about such things:

And what remains when disbelief has gone?

Grass, weedy pavement, brambles, buttress, sky

How close those lines feel now to what I experienced in Barcelona—and also how distant. Can that really be all he felt in all those churches? Was he quite so empty? Didn’t the grass and the sky mean anything to him?

So opposed to modernism were they that Amis and Larkin simply degraded it, and thus became unserious. In one letter, talking about a book by Robert Graves, Amis says it contains,

… accidental good talk (…nasty remarks about Milton and Kipling, an attack on reading poetry aloud), and the inevitable piss about ‘modernist poetry’ which means E.E. Cummings—honestly have you ever thought C was worth anything?

Enjoyable stuff in small doses. But hardly a basis for living or criticism. I prefer, against Amis’s saloon-bar coarseness, Larkin’s simplicity:

Betjeman was the writer who knocked over the ‘No Road Through to Real Life Signs’ that this new tradition had erected.

And when he edited his anthology of Twentieth Century poetry, Larkin was admirably honest.

I’d always vaguely supposed that the by ways of 20th century English poetry were full of good stuff, hitherto suppressed by the modernist claque: now I find that this isn't so. Gibson, for instance — a lifetime of books, ending with a Macmillan’s Collected Poems just like Yeats or Hardy or C. Rossetti: never wrote a good poem in his life. Grim thought. Endless verse plays! People like this make Rupert Brooke seem colossal.

In his finer moments, this is the reactionary Larkin I admire: witty, self-effacing, narrowly aesthetic, honest, mildly disappointed that his ideology didn’t work. Subtly aware that modernism was a success, even if not to his taste. Bloody funny about Rupert Brooke.

That spirit is concomitant with the Larkin who wrote: “My ideal writer wd be a mixture of D.H.L., Thomas Hardy, & George Eliot.” The Larkin of minor sorrows who wrote to a friend, when a student: “The days are like a beer tap left turned on — jolly fine stuff all running to waste.” The Larkin who could joke in his letters, “Ted Hughes is coming here to read in the autumn: tickets £1.50 but for £4.50 you can go to a reception and ‘meet Ted Hughes’ . . . Feel like walking up & down outside with a placard reading ‘Meet P.L. for £3.95’. I really must arrange to be away that evening.”

still going on!

Whatever else he was, Larkin was a poet of the almost. That haunting line from the Whitsun Weddings—As if out on the end of an event/ Waving goodbye—can be felt almost everywhere in his work, prose or verse. It is that which makes it harder to go back to his poetry now. Separating the half-cut racist from the lyric poet is possible. We can despise and dislike the man and still enter into the dream of the poetry. What should challenge us in the letters is not the same as the challenge of the work.

One reason why I return to Larkin is that as one gets older the strength and pain of being young becomes smaller and clearer as the years go by, and what becomes more intense is the feeling that “at once whatever happens starts receding.” You know, more and more, what he meant about being out on the end of an event—and more and more appreciate the power of the poetry to change that.

As Gioia says,

The special power of Larkin’s poetry is that it earns its joy, humor, and compassion by working through equal measures of pain, depression, and resentment. The reader always feels the price—and therefore the value—of its hard-won clarities… Toward the end, Larkin complained to Motion that, having stopped writing, all the poet had was “a fucked up life.” Reading the sadder chapters of his biographies, one is inclined to agree—until one turns back to the poetry.

I have children now. I see the time passing in their faces, their lengthening limbs. I hear the echo of their smaller selves in their growing talk. And so I read Larkin with a different kind of regret. Not the enjoyable cynicism of youth, but still with something of the strength and pain of being young, and of being not so young as before.

Truly, though our element is time,

We are not suited to the long perspectives

Open at each instant of our lives.

They link us to our losses: worse,

They show us what we have as it once was,

Blindingly undiminished, just as though

By acting differently, we could have kept it so.

One poem that means more and more to me, which meant almost nothing to me twenty years ago, is ‘Dublinesque’, which describes a funeral. Unlike ‘Ambulances’, this is not about “the solving emptiness/ That lies just under all we do.” Rather, ‘Dublinesque’ is a celebration, a remembrance.

There is an air of great friendliness,

As if they were honouring

One they were fond of;

Some caper a few steps,

Skirts held skilfully

(Someone claps time),

And of great sadness also.

As they wend away

A voice is heard singing

Of Kitty, or Katy,

As if the name meant once

All love, all beauty.

This is the best of Larkin, a poet who sees there is something worth the lament, some part of life that ought to be regretted and preserved—a poet, that is, who is bittersweet not bitter, who wants to “Bring sharply back something known long before”, as he wrote in ‘To the Sea’. This Larkin knows that life is “Still going on, all of it, still going on!” and that

It may be that through habit these do best,

Coming to the water clumsily undressed

Yearly; teaching their children by a sort

Of clowning; helping the old, too, as they ought.

An excellent essay, and that comparison with Keats is fascinating. Whenever I teach The Whitsun Weddings I linger over this line: 'sun destroys/The interest of what’s happening in the shade', because I think Larkin is preoccupied with the shadows, and clarity, sunshine, reduces that ambiguity to something more exposed and less complex.

Thanks for this lovely essay. If you haven’t done so already, I would highly recommend listening to his recording of his poems on “The Sunday Sessions,” which is available as an audiobook. Despite his reservations about reading poetry aloud, he was a magnificently sensitive reader, and one of the rare poets who was an ideal reader of his own poetry. His readings of the handful of poems from “The North Ship” are particularly touching for their sense of fondness and regret for the earlier poet who wrote them, a nascent Keatsian (and Yeatsian) poet that Larkin had long since lost. You can tell he knows the poems are not as good as his more recent work, but that he still feels “the strength and pain” of them. Hearing it adds a lot to one’s sense of the man.