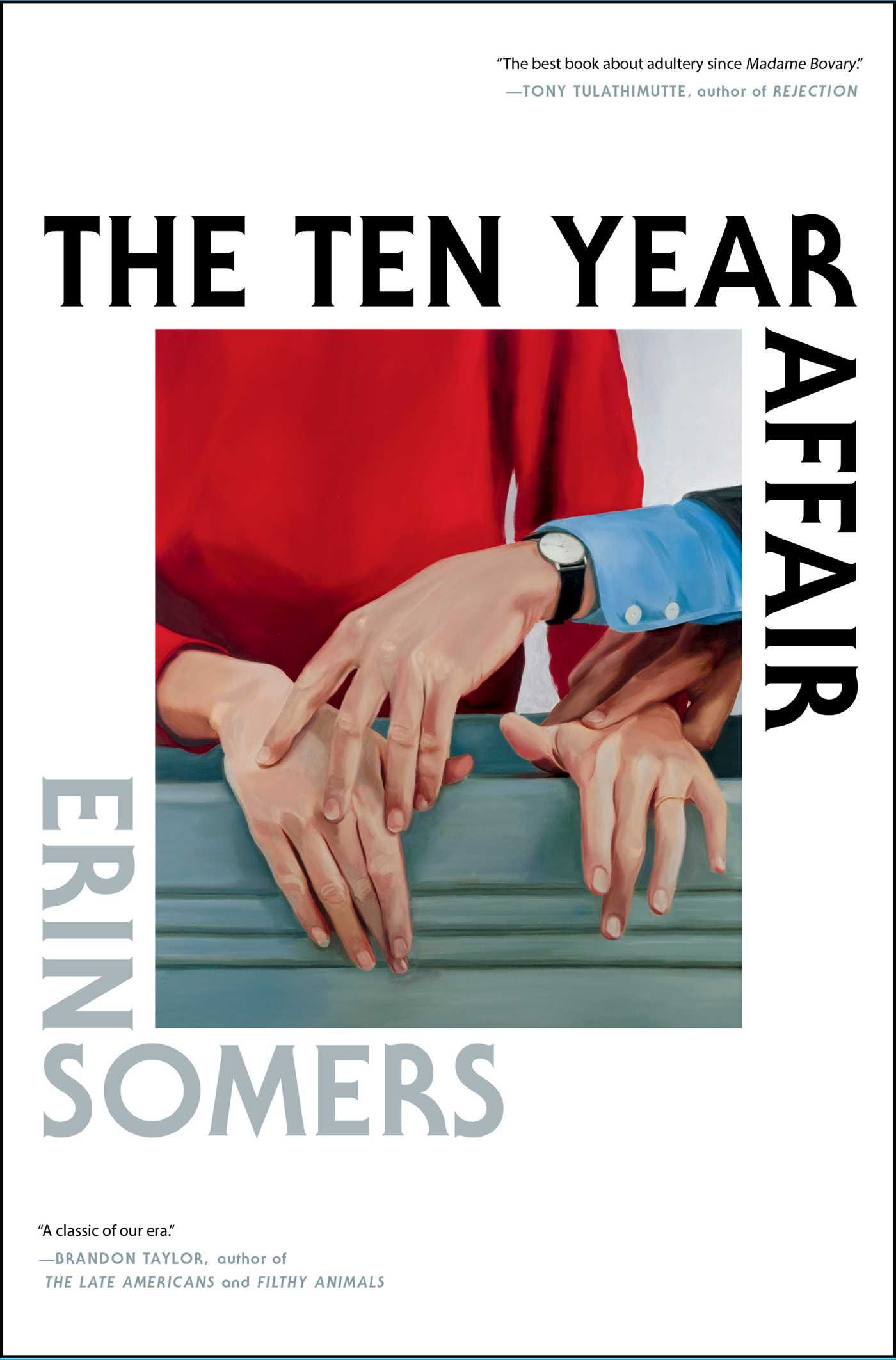

The Ten Year Affair, by Erin Somers

Inverted Free Indirect Style

Whatever else you might say, this book is frequently quite funny.

“You’re like that guy in that thing,” she said.

They had been married long enough for him to know that she meant the main character from The Sun Also Rises who’d had his dick broken off—blown off?—in the war. The book was poignant because he could not fuck his girlfriend. At the heart of their interactions was their inability to have sex. This was accurately positioned as the most tragic thing that could ever happen.

“Don’t compare me to Jake Barnes,” he said. “This isn’t like that.”

Among other things, the metaphor was grandiose. What, for instance, would be the equivalent of war.

“Don’t say capitalism,” he said. “Don’t say weed.”

The joke lies in the fact that “Don’t say capitalism” is not only exactly what these sorts of people would say, but also in the fact that this is exactly what the readers of this book would often say. Erin Somers is “funny on Twitter” and this is the sort of comic observation that would be part of the politico-humorous discourse which prevails online. Alas, Somers frequently has to write in the style or tone she wishes to mock (either from stylistic choice, to present the reader fully with the world she wishes to ironise, or as the inevitable result of being “too online”,—a distinction which may be, for many “discourse novels”, unhelpful).

So the cost of her jokes is an inversion of the usual use of Free Indirect Style. The typical method is that the thoughts or phrases of the character are ventriloquised by the narrator. Thus, from Bleak House:

Mrs. Perkins, who has not been for some weeks on speaking terms with Mrs. Piper in consequence for an unpleasantness originating in young Perkins’ having “fetched” young Piper “a crack,” renews her friendly intercourse on this auspicious occasion.

That phrase “in consequence for” has no speech marks, but it plainly belongs to Mrs. Perkins, not to the narrator. In The Ten Year Affair, Somers uses this technique to import not her characters’ thoughts, but what we can think of as either her own idiom or the standard usage of her corner of Twitter (again, the distinction is not mine to resolve, and may not be resolvable).

Cora thought about her interactions with Sam so far. She felt possessive of him. She thought Eliot and Sam would get along. She could picture their pleasant, dick-swinging camaraderie. The way they’d know common people from the schools they’d attended. The way they’d bond over totems of millennial soft masculinity: craft beer and Knausgaard and basketball and socialism.

Whose phrase is “totems of millennial soft masculinity”? It might be an example of Free Indirect Style from Cora, but it is too generic; really, we feel this is drawn not from Cora’s consciousness, some perspective in the novel that is distinctly hers, instead, this feels like Somers, or some version of Somers’ Twitter personality, which, as with all Twitter personalities, is derived from the common stock: as with jokes, social media aphorisms take forms and modes that are inherently anonymous. Totems of soft millennial masculinity is such a phrase. This is an inversion of Free Indirect Style—ventriloquising discourse from outside the novel, which is relevant to the characters, rather than ventriloquising discourse from inside the characters that is relevant to the novel.

There are moments when this Anonymous Twitter Style is so pointed that you could mistake Somers’ writing for Patricia Lockwood’s, an odd experience as they are not especially similar writers.

Cora’s father had been cremated, but she didn’t want to broach the topic of cremains. That was objectively scary. They put his body in an oven and burned him to ash. Sweet dreams!

That sardonic Sweet dreams! after the use of objecively is a perfect example of the anonymous joke-style that prevails online (and in Lockwood). You see this anonymous joke-style, too, in lines like: “The book was poignant because he could not fuck his girlfriend.” As I say, one result of this is that the jokes about the characters (who are just as trapped in their discourse as the novel) are rather good.

“I propose a getaway,” said Cora.

“Where to?” said Eliot.

“Where are they in those Gauguins? With the fruit and the women?”

“Tahiti.”

“Yeah. Tahiti. Let’s book a trip.”

“I wish.”

“It’ll be great. We’ll lie on the beach. Drink cocktails out of coconuts. Stay in one of those villas out over the water.”Eliot put his mouth directly under the faucet and turned it on.

“Wow,” said Cora.“There are no glasses.” He wiped the back of his mouth with his hand. “They’re racist, those Gauguins. I read an article about it. You know, the noble savage? He’s got a mixed legacy.”

“Oh,” said Cora.

“Plus, the girls in the paintings were children. Definitely too young to be sexualized.”

“Right, okay. No vacation then.”

“We could go to the movies. You love the movies.”

The Ten Year Affair is not, as Tony Tulathimutte said, the best adultery novel since Madame Bovary. (Why put such a silly claim on the cover? Some people have mentioned Tolstoy as the obvious rejoinder. We can also add Henry James, Graham Greene, Evelyn Waugh, Ford Madox Ford, Somerset Maugham, Elizabeth Jenkins, Sebastian Faulks, Edith Wharton, Kingsley Amis, Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce, Iris Murdoch, Marcel Proust, and others to the list.) But it is very entertaining, well-written, and despite the oddities of the narrative techniques, it stayed with me more than I expected. In some ways, I enjoyed this book more than I realised I did as I read it.

I think one of the oddities of Twitter Style is that it blurs the lines between "inner thoughts" and "outward speech". Namely, both involve impulsively producing half-formed thoughts that are not necessarily directed at anyone or anything in particular. If you tweet a lot, I wouldn't be surprised if you start naturally molding your thoughts to look a bit more like tweets, so as to improve the efficiency of the thinking-to-tweeting pipeline.

All that is to say, if you have an author who is Funny on Twitter writing a character who is terminally online, it may be impossible to say where the Free Indirect Style begins or ends.

I've been reading Jonathan Strange & Mr Norell and wondering about the 19th-century-ish writing device of some omniscient narrator interjecting with asides and or even moving the story one... Now I know it's called Free Indirect Style. Thank you.