Sex, madness, and death. Elizabeth Jenkins' overlooked masterpiece.

Obscurity in the age of Martin Amis's leather jacket.

The first part of today’s post is what I wrote in the most recent edition of Prospect’s Culture newsletter. Last week was the seventieth anniversary of Elizabeth Jenkins’ novel The Tortoise and the Hare, and this piece is an overview of her best novel, her life, and a call to bring some of her other work back into print. What are the publishers waiting for?

The second part is for paid subscribers and gives you some of the details of the sex, madness, and death in Jenkins’ life, including the real affair that inspired the novel. I also explain what makes Tortoise more interesting than the other adultery fiction of the 1950s, including works like The End of the Affair.

A few years ago, I picked up The Tortoise and the Hare, Elizabeth Jenkins’s classic 1954 novel, and swiftly abandoned all professional and family responsibilities until I had finished it. Tortoise is a quiet knockout, a why-haven’t-I-heard-of-this-before classic. If you haven’t read it yourself, turn off your phone and tell your partner, children, pets and flatmates to fend for themselves.

This month—tomorrow, in fact—is Tortoise’s 70th anniversary. It was a hit in 1954, and, after it was republished in the 1980s by Virago Books (which itself turned 50 last year), it has been repeatedly reprinted.

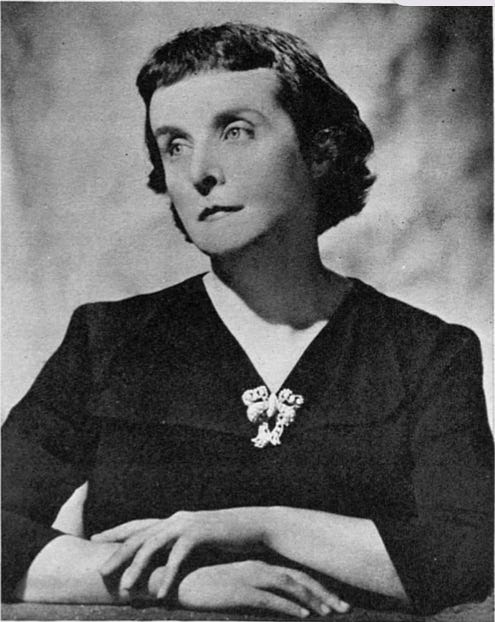

Jenkins was a respected writer in her time. She won the Femina Vie Heureuse prize in 1935 (beating Evelyn Waugh) and was much praised for her biographies of Austen and Elizabeth I. To her friend Elizabeth Bowen, Jenkins was “among the most distinguished living English novelists.” Carmen Callil told me Tortoise was her favourite of the Virago Modern Classics.

And yet, Jenkins is a little forgotten today. Only two of her 24 books are in print. She is one of the major mid-century women writers (Bowen, Rosamond Lehmann, Rebecca West… and, until very recently, Barbara Comyns) who doesn’t have a biography. Books about so-called “middlebrow” women’s writing typically give her little, if any, space. Three of her best novels, Dr Gully, Honey, and Brightness, languish on the backlist, even though her work is topical, dealing with issues of adultery, divorce, lust, betrayal and sometimes murder. And Jenkins’s writing is easily the equal of other women writers whose work has been revived. Ignoring her like this is absurd.

Tortoise is the story of an affair. Imogen Gresham, young and beautiful, is married to Evelyn Gresham KC, a handsome and impressive barrister. Blanche Silcox, their country neighbour, is a dumpy, frumpy, middle-aged woman whom Evelyn admires but whom Imogen finds irritating. It becomes obvious to everyone—apart from Imogen—that Evelyn and Blanche are having an affair. In the face of this betrayal, Imogen is submissive. Gaslighted by Evelyn and mocked by Blanche, Imogen sinks into a stupor, unable to confront the truth. As her cruel son says, “all she does is suffer.” Though Evelyn leaves Imogen for Blanche, the ending is surprisingly optimistic.

Tortoise stands out against other “adultery fiction” of the period: it is not conventional, predictable or routine in any way. Of the many adultery novels of the 1950s, Jenkins’s is the only one about a man leaving his young, beautiful wife for an older, less conventionally attractive woman, in which the last chance for love is seized by an otherwise ignored middle-aged woman. Though Jenkins was a traditionalist—a Telegraph-reading Tory and a Christian of strong belief—Tortoise is ultimately ambivalent about divorce.

The plot has some basis in reality. In 1944, Jenkins started an affair with Sir Eardley Holland, a prominent surgeon and gynaecologist. His wife Dorothy was ill in the countryside, having suffered a stroke in 1939, and Jenkins thought Holland would marry her once Dorothy died. But Sir Eardley married another woman—a woman who was older and less attractive than Jenkins. Heartbroken and astonished, Jenkins turned her rage and depression into Tortoise.

Jenkins’s deep feelings of betrayal give the book its power and inform her unflinching portrait of Holland’s abrasive, supercilious manner. One reviewer said Tortoise was “a novel many women will read with horror and identification.” The portrait of Blanche is hilariously sharp (it had to be toned down to avoid libel). Everyone I recommend Tortoise to later quotes something about Blanche that made them laugh with malicious glee. As AN Wilson (a friend of Jenkins) said to me: “It is a vicious book, which is why everybody who reads it for the first time is so gripped by it.”

Honey is a splendid novel about a Marilyn Monroe-esque woman who wants to sleep with her stepson: she’s so used to being adored that she can’t stand the fact it won’t work on him. Dr Gully is an outstanding historical novel about an affair between the renowned Victorian hydrotherapist James Manby Gully and Florence Bravo, and the subsequent murder of Florence’s husband, Charles. The abortion scene is especially vivid. Why these books are not in print, God only knows. Honestly, take the day off and read one of them in the British Library. You won’t be disappointed.

Jenkins has a great ability to control pace and tone. You won’t find a paragraph out of place. John Betjeman said of Tortoise, “I do not think there is a sentence in this book out of character.” And she is masterful at portraying a whole psychology. Though Tortoise originated in profound personal pain, it is remarkably balanced. One lifelong friend used to say that Jenkins was so in love, she just couldn’t forgive the woman Eardley Holland married. And yet Blanche, the character based on that woman, is made more and more sympathetic as the book goes on. Her happy ending is presented with equanimity. Understanding Blanche rather than merely bitching her, is the great achievement of Tortoise. Jenkins created a genuine, sympathetic character out of a woman she loathed. As Elizabeth Bowen said, “Blanche is Miss Jenkins’ masterpiece: grotesque as she is, this woman is given dignity—she has been evoked for us with uncanny insight, rendered for us with consummate art.”

It is understandable that this sort of subtle and accomplished writing fell out of favour in the age of Martin Amis’s leather jacket. The same thing happened to the magnificent genius Penelope Fitzgerald, whose work was overlooked by so many people less dazzled by old ladies than by enfants terribles. But the revival of mid-century women novelists is now firmly established. Stella Gibbons has been reprinted. There is a new (and very good) biography of Comyns. It really is time for Elizabeth Jenkins to get the recognition she deserves and for someone to publish some of her other books.

Elizabeth Bowen once said that “Miss Jenkins is a major novelist, from whom the terror and greatness of life are not hidden.” Until someone republishes Honey and Dr Gully, the terrors and greatness of Elizabeth Jenkins will continue to be hidden from readers.

“She entertained us with stories of crimes, murders etc”

Bowen was right. Jenkins had a dark side. All her best work is about sinners, people who go mad, people who verge on criminality, or who blunder into it. Tortoise has the feeling of impending murder. As was said on the Backlisted podcast, “it feels like a crime is being committed, but where is the crime?”

The Canadian diplomat and diarist Charles Ritchie, who had a long affair with Elizabeth Bowen, had tea at Jenkins’ house in 1942. His observations are a little exaggerated but offer an outsider perspective that gives a glimpse into this side of Elizabeth’s personality.

The rest of this piece, which covers the dark side of Jenkins’ personality, the morbid books of poems she gave to Holland at the start of their affair, and 1950s adultery fiction—sex, madness, and death—is for paying subscribers.

She is an odd little creature, with a 1921 face and style and hair-dressing a rather sweet and naive manner which does not altogether conceal a strong and rather disturbing personality. She entertained us with stories of crimes, murders etc of which she has made a special study. It seemed dream-like to be sitting in the Regency drawing-room of her little Hampstead house, among the pretty china and flowers, while she went on in her rather too refined and Elgar voice telling of one gas lit Victorian crime after another. The surface was Cranford a genteel little person who eked out a modest income by giving music lessons and who was pleased if you took a 2nd slice of her almond cake but there was something faintly disturbing which still lingers in my mind like an unexplained smell. In fact her novel ‘Harriet’ which is a reconstruction of a murder story almost affected her brain — she came to identify herself with the murderess heroine and had in the end some sort of nervous collapse.

Despite the sweeping nature of this passage, and its slightly unverified remarks (did Elizabeth Bowen tell him these things?), it is worth taking seriously. Elizabeth was always interested in nervous collapses or mental disturbances. Her novels The Winters, Harriet, and Robert and Helen all deal with this, always hereditary conditions. Her work often involver her pushing herself to the edge of what she was capable of. She told the Daily Mail she won the Femina Vie Heureuse prize for Harriet, “It involved greater strain than any other novel I have attempted… Another such book would [land] me in a lunatic asylum.”

Later in the same entry, Ritchie records a story Bowen told him about the otherwise unrecorded row that ended Jenkins’ acquaintance with Virginia Woolf.

V confessed that she had not spared her but she said in self extenuation: “she came in dressed up as Caro. Lamb holding a muff ... and looking like a little dead bird.’’

It is odd that this story doesn’t occur in Woolf’s diaries or letters, despite other impatient and disparaging remarks about Jenkins. But Bowen is reliable, and she knew Jenkins and Woolf; and this sounds like Elizabeth, the woman who spent a great part of her later life absorbed in spiritualist practices to contact James Manby Gully in the afterlife, including practising automatic writing and using mediums. In her younger life, she was fascinated to the point of absorption by Lady Caroline Lamb. “I dislike the people who dislike my heroine,” she wrote.

A.N. Wilson said that Elizabeth “lived in the past” and it is not difficult to imagine her doing that almost literally. This is what makes her writing so vivid and real. But Tortoise is a reaction against her early infatuation with Caroline Lamb. In 1973 she wrote to George Rylands when Lady Caroline Lamb was reprinted, “Since I wrote that book, we have had so much experience of selfish neurotics, wrecking other people’s lives, I could never now devote so much sympathy to one of them.”

The quote, of course, shows just how devoted she had been. It sounds like a reverse conversion. The deeply immersive side of her personality, combined with the dark undercurrents noticed by Charles Ritchie, were all at play when she sat down in a state of broken-hearted despair to write Tortoise. This is a testament to her ability to transmogrify her material into fiction.

A strange affair

The reason for the end of the affair was simple: sex. Writing to the historian A.L. Rowse in 1961 about her two successful books about Queen Elizabeth I (which contained controversial theories about Elizabeth’s sex life), Jenkins said she had an advantage in understanding the queen because,

…she was no good in bed, and I am not either… Of course, her condition was exaggerated to absolute neurosis (I suppose) and mine is just incompetence, finding the episode awkward, painful and dismaying, which lost, or helped to lose me the one man I really adored.

It was a very strange affair. In 1944, shortly after the affair started, Elizabeth gave Eardley a handsomely bound, hand-written book, with thick, calligraphic writing. It is not a book of love poetry, but a selection of thirteen pieces of writing about the death of wives, often in childbirth.

Called A Garland of Yew, it begins with an extract from The Ballad of Clerk Saunders, in which a male speaker encourages a woman to sleep with him before marriage. When her brothers discover this, they kill the man. In the passage quoted, Saunders’ ghost is at the window, asking for one final kiss. In the full version, Saunders’s ghost leaves his lover forever.

In many of the poems, a woman and her child have died. In some, the child survives. Titles speak for themselves. “On his deceased wife”. “On an infant dying as soon as born”. “A monody on the memory of his wife’” This theme recurs in Jenkins’ novels. In books like The Winters, Honey and A Silent Joy there are children who have lost their parents. That is also the case in Elizabeth Bowen’s novel The Death of the Heart, a major influence on Jenkins.

There is also a letter from Clarissa describing death by childbirth, an extract from Malory (“How Sir Tristram of Lions was born and how his mother died in childbirth”), and some quotes about Jane Seymour’s death.

There are no surviving letters or diaries of the affair. So we cannot know why this book exists. But it is worth considering the options.

The most mundane explanation is likely to be correct. Holland and Jenkins were both interested in history. In 1951, at the end of the affair, Holland published a scholarly paper on the causes of Princess Charlotte’s death in childbirth. (The princess appears in Elizabeth’s 1968 novel Honey, on a tea tray which reads: “England mourns her Princess.”) One of the final selections in the book is the Elegiac Verses on the Death of Princess Charlotte from Childe Harold and Holland quoted Byron in his article.

The selections are linked to Holland’s work in other ways. Two of the passages (the letter from Clarissa and an epitaph about Jane Seymour) blame medical inattention for the death of the mother. Holland’s correspondence with his colleague Grantly Dick-Read shows his interest in the improvement of childbearing and labour.

The book might be nothing more than a selection of writings about an area of overlapping interest between two people in an intense but possibly chaste relationship.

And yet. There is something disturbing about this book when we know Eardley’s wife had been debilitated by a stroke five years earlier. Jenkins her only public comments about Dorothy, made many years later, were remarkably unsympathetic.

More speculatively, it is impossible to avoid thinking about whether Jenkins had an abortion (or miscarriage). If so that might explain the mordant selection. In Dr Gully Jenkins told the story of the relationship between James Manby Gully and Florence Bravo. Gully was a Victorian doctor, renowned for his practice of hydrotherapy, who treated luminaries like Darwin and Tennyson. One of the most vivid scenes occurs when Florence gets pregnant, and Gully performs an abortion. Their relationship never recovers, sexually or psychologically. It is the climax of the book.

Jenkins was as obsessed with Gully as she was with Holland. Dr. Gully was her favourite of her books. It is wild speculation to trace back from this novel to her life, but her love for Gully means he was, in a sense, her Eardley substitute.

Most striking is that the extracts are all anti-sex. Jenkins was horrified at the idea of childbirth from a young age. Rather than being a book about the passion at the start of an affair, it is a selection of omens about the end of one. For centuries, writers have written witty, sophisticated poetry to encourage women to sleep with them. Elizabeth outwitted them by creating an anthology more likely to act as contraceptive than aphrodisiac.

Whatever the truth about this book, only something very strange accounts for it. That is really as much as we need to know.

“Adultery fiction” and the rise of divorce

Despite the fact that Jenkins was a traditionalist, a good-old-fashioned Telegraph reading Tory, and a Christian of strong belief, Tortoise is ultimately ambivalent about divorce: it causes huge pain but also improves the characters’ lives. For this reason, Tortoise stands out against other “adultery fiction” of the period.

Divorce, adultery and marriage are preoccupations of 1950s realistic fiction. The End of the Affair by Graham Greene, one of the most enduring novels of the decade, details the haunting effects of a wartime affair on a woman’s husband and lover in the post-war world, while she is dying and secretly converting to Catholicism. Like Tortoise, Greene’s novel works to make the reader sympathise with all three members of the love triangle. Penelope Mortimer started writing fiction under her own name in 1954 with A Villa in Summer about a barrister and his wife whose marriage comes under strain when they move to the country temporarily and he (a divorce lawyer) nearly has an affair with a local headmistress. Iris Murdoch experimented with a realistic romance about a school master falling in love with an artist in The Sandcastle. Isobel English published three short, sharp novels about adultery, starting with The Key that Rusts. (Her second novel, Every Eye, has recently been re-published by Persephone.)

In all of these works, the terms of the affairs are conventional: a man and woman of either the same age or where the woman is younger, prettier than the man’s wife, and oddly compelling in some way. (A.S. Byatt didn’t think Murdoch’s novel “escaped” being “a woman’s novelette.”)

In Greene’s novel, as in The Key that Rusts, the affair is doomed not just for external reasons, but because of some incompatibility between the lovers. In A Summer Villa, the affair never quite begins for the same reason. These novels do not confront divorce. In The Key that Rusts, Sam leaves his wife to devote himself to Mary—and yet remains an incorrigible womaniser. It is not a novel about a serious affair between sensible adults.

Tortoise, though, is exactly that. Tortoise is the only example of a successful adultery, where the marriage ends and, although the whole thing is extraordinarily painful, the new situation is probably better for all three characters. There is hope at the end of Tortoise in contrast to The End of the Affair. Jenkins is the only one who produced a novel about a man leaving his young and beautiful wife for an older, less conventionally beautiful woman, in which the last chance for love is seized by an otherwise ignored middle-aged woman.

In 1956, a Royal Commission on marriage and divorce produced a report which identified the pursuit of personal pleasure as a significant new factor in the increased rate of divorce. Some members of the Commission proposed “irredeemable breakdown” as a new ground for divorce based on this new trend. This scandalised the other half of the Commission. It was not a new idea, but it was so controversial that it wasn’t implemented until 1971.

This is exactly what Tortoise is about: the rise of people doing what they want rather than what they ought. Evelyn and Imogen’s marriage has indeed irretrievably broken down. Evelyn’s infidelity is a symptom not a cause. Imogen is a genuinely new, perhaps radical character in this context. When the backbench MP A.P. Herbert introduced the 1937 Divorce Act, the results of which led to the Royal Commission, it was wives who opposed him, “both elite and working class.” One of his strongest opponents was the Mothers’ Union. Herbert was bitter about this, calling marriage laws “the most profound instrument ever invented for the extraction by the female of ease and comfort and money from the male.” Despite the sexist framing, this is the sort of heartless exchange Imogen and Evelyn have descended to Carmen Callil says something similar in her afterword to the Virago edition.

For Imogen to break from this mould, as she does at the end, to become independent, to accept the new social and moral order and get on with her life, makes her a more imaginative and prophetic character than many other wives in contemporary adultery fiction.

I'm glad to find this right after reading The Tortoise and the Hare--what a superb introduction to a neglected author.

Adding the Tortoise and the Hare to the list now for sure. I'm often surprised to see twitter users astounded that a person's affair / side chick / mistress might be less attractive than their established partner because that displays such ignorance of how sex and love actually happen in real life. It seems to me like from what you said Jenkins was also intially ignorant of it and then felt betrayed by her experience, *but then engaged with her disappointment and betrayal and made art about it*, which makes all the difference. Totally excited to read it.