The untold life of Helen Taylor

How personality spreads ideas

The next Western Canon book club is about Turgenev, October 17th. The next Shakespeare book club is on October 13th.

In case you missed it, here is my review of the new Sally Rooney novel, Intermezzo

Helen Taylor’s diary

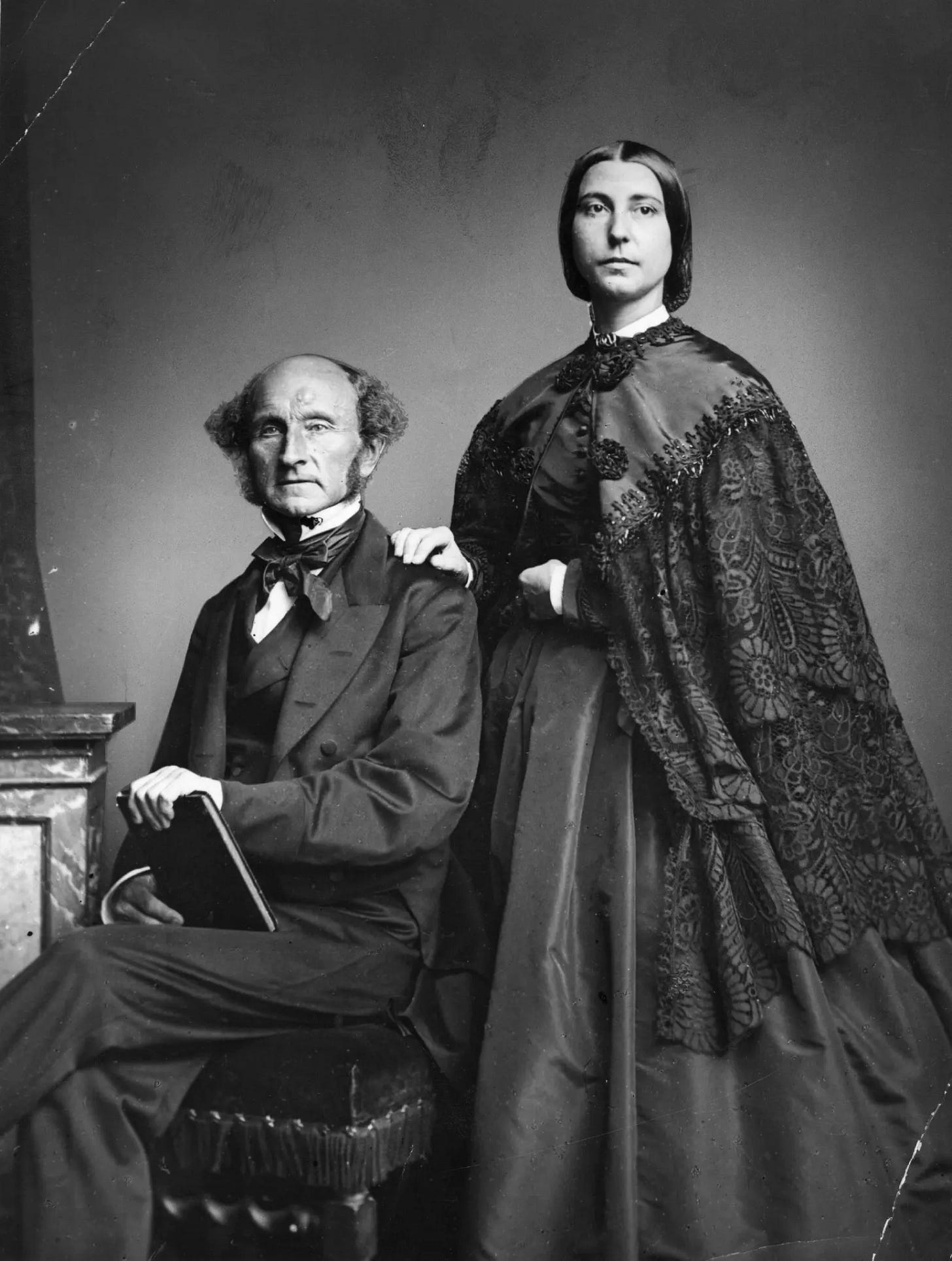

At the end of last year, I spent a happy week in the Mill-Taylor archive at the London School of Economics. I didn’t expect to find anything hugely new, after all, John Stuart Mill and his collaborator-wife Harriet Taylor Mill are among the most studied of the Victorians.

But in the miscellaneous papers I found two intriguing documents. They were two diaries, one by Helen Taylor, one by her niece Mary. Helen was Harriet Taylor’s daughter, who was adopted by John. Neither woman, nor their diary, gets much attention. But, they should. Helen worked closely with John Stuart Mill after her mother’s death and was, in her own right, an essential part of the women’s suffrage movement in the late nineteenth century.

When Helen is written about, it is to reclaim her as a Victorian woman whose work has been overlooked or undervalued. That’s an important part of her life. But though Helen is sometimes admired for her public work, not much attention is paid to her personality. Who was this impressive woman and what animated her?

The two diaries at the LSE contain a lot of information about Helen’s character. They cover her teenage years and her dotage. They don’t tell us about her public achievements or her life with Mill. But they do show us who this woman was who did so much, who was so committed to her causes, who worked with such dedication.

And they complicate the story. To read the Dictionary of National Biography, you would think Helen was a liberal feminist and little more. She fits a pattern that we are comfortable with. But the diaries show a much more varied person.

As well as telling the sorry story of how this great woman became a lonely old lady, these diaries show the importance of religion, and religious-type zeal, to Helen’s secular work (and, by implication, its importance to Mill’s work too.) What they show together is just how dominating temperament is over ideas. Helen did an immense amount of useful work because of her devotional personality.

She is a powerful example of how ideas are spread through people.

Two childhoods

As a child in the 1840s, Helen wrote in her diary about her disgust at the behaviour of some poor children, who were throwing stones at a donkey outside her window. She was further appalled to see the father come along and kick and beat the children. Her diary is fierce and condemnatory of this behaviour, and of the poor in general. What a contrast that makes with her later work. The girl who had despised those poor boys became a woman committed to making reforms on their behalf, a heroine of the working classes. Helen outgrew the prejudices of her class background as she developed intellectually.

Some sixty years later, staying in a hotel with her niece Mary in 1904, Helen made a request that Mary found very odd—could a child be found who could sit with her? Helen had become an irritable, often unkind, old woman. Mary is constantly frustrated and upset: her diary is full of arguments, bitterness, and frustration. The request to have children sit with her, Mary assumes, is because Helen knows no-one else would want to. In the end no children were found: against her wishes, Mary stayed with Helen.

That night, Mary set down an ultimatum. Helen would have to pick between her servants or her family, who Mary felt were exploiting Helen in her diminished state. And this meant that Mary was side-lined, with no responsibility or authority in the house. She was trapped.

They had left their home in Avignon, France, to come to England so that Mary could take care of Helen: but it also meant she could make this ultimatum on neutral ground. Every time the question had come up before, Helen lost her temper and told Mary to move out.

The tension came from Helen’s diminished mental state. She had evolved from a child who found working class children repugnant, into a woman who campaigned tirelessly on their behalf, but was now a lonely old woman who felt that the only person who might sit with her was a local poor child, in exchange for Helen paying their doctor’s bill.

Helen had become nervous and narrow. She had once been a great champion of women’s rights—now she wouldn’t even let Mary take a share in helping to run the household. Some of what Mary takes to be controlling and nasty behaviour, like constantly summoning the same servant up and down the stairs for little reason, is part of a larger pattern of behaviour which suggests some form of dementia. In Mary’s diary, Helen seems paranoid, has sudden mood switches, and, according to Helen, had lost a lot of her memory. And Mary was convinced the servants were untrustworthy, taking advantage of Helen’s poor mental state.

Helen had become miserable at Avignon, the house where she had done so much important work with Mill. Mary writes that Helen’s only activity was to mope around the garden, picking up leaves and twigs. Now, in England, Helen agreed with Mary, saying, “I feel quite a different woman from what I was when I was with those people you don’t like.” Considering those were Helen’s own servants, who she had lived with for years, that phrasing—those people you don’t like—seems like a clear sign of Alzheimer’s.

This was a sorry decline from the years of Helen’s accomplishments.

Casting off the trammels of skirts

Unlike other Victorian feminists, such as Emily Davies who helped found Girton College, Helen Taylor has no one major achievement. But political movements require people who will organise and proselytise, who write letters, keep focus on the right issues, who spread good ideas. If liberal ideals were going to succeed, they needed the work of people like Helen Taylor.

When Helen was twenty-seven, her mother, Harriet Taylor, died. Helen immediately left her career as an actress to live with Mill, and became his collaborator, editor, and amanuensis. She wrote many of his letters about women’s suffrage—Mill said he bowed to her superior knowledge. She wrote the wording of the petition for women’s votes that Mill presented to Parliament. She edited and published the works of the historian Henry Thomas Buckle. She also edited and published many of Mill’s own works, including the Autobiography, and his final essays on religion and socialism. She was a founding member of a women’s suffrage organisation and participated in the Kensington Circle, a women’s debating society.

Helen was an independent thinker, more concerned with doing what was right than with fitting in. When she was involved with socialist organisations, they disliked her feminism; and the feminist organisations she supported disliked her politics. Her agenda was entirely hers. She wasn’t a partisan for any organisation or any group.

She campaigned for Irish Home Rule, opposed fox hunting, and was a member of the Moral Reform Union to oppose Victorian prostitution laws that punished women not men. As an elected member of the Southwark School Board, she advocated for free and universal education, the abolition of corporal punishment, community use of school facilities outside of school hours, and free meals and clothing for needy children. She also got working class parents appointed to school manager roles. In 1885, she stood for Parliament, drawing much mockery, disapproval, and condemnation. The Saturday Review said, “for electoral purposes she is non-existent.” However, she had huge influence among the working class voters, because of her service on the School Board.

Richard Pankhurst spoke on Helen’s behalf in the 1885 election, but many in the women’s suffrage movement kept their distance from “that very drastic lady.” As Sylvia Pankhurst recalled, “The fact that Helen Taylor cast off the trammels of skirts and wore trousers was an added and most egregious offence in their eyes. Even Mrs Pankhurst was distressed that her husband should be seen walking with a lady in this garb.”

As Janet Smith said, Helen was the sort of feminist who “believed that women and men were different and that without women’s inherent moral goodness democracy would never be lifted out of the corruption they believed it was mired in.” Helen didn’t want “separate spheres” for men and women: she thought they should work together, integrated.

The evil spirit

As an old lady in Avignon, this was all gone: Helen had been lost to her declining mind. In England, she was more active, helping Mary make petticoats for the unemployed in West Ham. A new routine was established, to bring Helen out of herself. But, the tension about the servants remained. The problem, in true High Victorian style, was that Helen’s will left her property to the French servants who Mary felt had manipulated their way to an inheritance: they had not even been feeding Helen properly.

Whenever Mary raised the issue, their new domestic calm was shattered. In an especially painful passage, Mary records, “she accused me of wanting her to die.” Mary’s diary is full of such glimpses of the torment Helen must have been feeling in those lonely moments. One day at tea, under the mistaken impression she was being taken back to France, Helen cried silently.

A day or two later, Helen made the new will and told Mary she was restored to health and happiness. As Mary said, Helen’s life at Avignon was really a living death. But with her declining mind, the only way out was painful, volatile, and erratic. Hard as it was for Mary to cope with this, Helen was lost to herself in many ways. A few days after the decision to stay with her family, not her servants, Helen’s mood changed. One evening she had kissed Mary and they both commented that it was like an evil spirit had been removed from Helen. “Alas,” wrote Mary, “we now know that it has returned.”

It was a long struggle to find Helen some contentment in her final years.

Daring to speak her opinion

Helen’s diary is from the 1840s, when her mother Harriet Taylor had left her husband because of her love for John Stuart Mill. Helen’s diary largely records her reading, travelling, frequent visits to church, and her evolving ideas about history and literature. Throughout the diary, she records visits from her father (Helen lived with her mother), her grandparents, and at one point from “Mr. Carlyle”, who she liked very much. But Mr. Mill never appears.

There was, by this time, a policy of secrecy between John Stuart Mill and Harriet Taylor. After their friendship became scandalous at the end of the 1830s, they went into a deep silence. Mill didn’t even tell his own family where he went on holiday. Helen’s diary reflects this policy. She was always very close to her mother and undoubtedly agreed not to mention Mill at all, even though he must have been there when Carlyle was, and on many other occasions, probably twice-weekly. Helen mentions one of Mill’s siblings, and an article about Grote’s History of Greece which Mill wrote, but never Mill himself. Helen’s silence shows respect for her mother and Mill’s relationship, and their work together. This respect eventually led her to change her life and work alongside Mill.

There are early signs of her commitment to feminism in Helen’s teenage diary—after she read Mary Wollstonecraft, she wrote, “Why do not people write now? Why is there neither man nor woman who dares to say his or her opinion openly and so that all may know it?” This entry shows us several important things. First, her use of “his or her”—Harriet Taylor was very concerned with the use of pronouns, persuading Mill at around this time to change the “he” and “him” in his Political Economy to “they” and “them”. Helen has obviously been influenced by this. Second, she is reading Wollstonecraft, and it is not outlandish to assume she is talking about feminism with her mother, who would shortly begin working on The Enfranchisement of Women, an essay that later became foundational to Mill’s book The Subjection of Women. Mill later credited Helen as an important original contributor to his work on feminism.

Most significantly, though, this diary entry shows us Helen’s uncompromising personality. Her call for people to dare to say their opinion openly so that all may know it, sounds very much like her mother and Mill do in their letters, and very much as they would sound a little over a decade later when they wrote On Liberty together.

To remember what Eternity is

Helen’s firmness of belief comes out most strongly in her religion. In a characteristic moment, she wrote, aged fourteen, “the sermon was finer than any I have heard. It was principally calling upon everyone to think and to remember what Eternity is.” Her diary records things like the way that nightingales sing her to sleep, her beach walks with her family, and her wide-ranging reading, especially of drama—she later became an actress. But religion was the heart of Helen’s life. Her diary is full of strong-minded opinions on sermons and comments about the way services were run.

In 1850, aged nineteen, she wrote a long reflection on Matthew 26:41, Watch and pray that you may not enter into temptation. The spirit indeed is willing, but the flesh is weak. That same year, she wrote long reflections on Ascension Day and on Sunday Within the Octave of Ascension. In the latter, she wrote,

epoch over epoch passes over our heads leaving us as it finds us, incredulous and hard hearted as to the things which it most concerns us to believe and to love.

These meditations include thoughts on the importance of periodically examining your conscience, on why innate factors make women more likely to perform nursing work, and on the fact that “the happiness of man consists in the practice of virtue.” John Stuart Mill would have agreed with the general tenor of this: he believed we all have a duty to improve ourselves morally. He and Helen’s later work together shares this guiding light—the imperative of goodness, progress, and virtue.

Believing the right ideas is not enough; we must live in the right way.

Helen retained her strict, outspoken personality. She was known for her unflinching capacity to express herself among the suffrage movement. The teenager who kept her own altar, wrote her own sermons, observed saint’s days, read the lives of martyrs, and critiqued Mass in Frankfurt (complaining how Lutheran it was because they spoke it in German), became the woman who once refused to share a stage with another member of the women’s suffrage movement because she disagreed with that woman’s personal morals. Her strong moral character extended in many directions, such as letting a farmer and his family live rent-free in one of her cottages because she admired them for adopting a little girl.

Helen’s diary is full of tolerance, too. She regularly went to Mass with her brother, Algernon, who may have been the one who converted her. But she also writes, more than once, that “we went to Mass.” Who is we? She always names Algernon; we implies the whole family. Elsewhere, Algernon recalled going to Mass with his mother and with John Stuart Mill. Mill also once reminded Harriet that they needed to plan their Easter trip to Italy so they arrived for Palm Sunday, for Helen’s sake. Despite his secular upbringing, Mill had a religious sister, whose husband was part of a sect in Plymouth. And Mill’s letters are full of references to him going to churches, and attending services. He was dizzy with admiration for the Catholic churches he visited in Rome. Helen was a Catholic in a family of Unitarians and free-thinkers. She was also part of a family that appreciated and tolerated religion, whatever their own beliefs.

In 1869, the height of the period when Helen campaigned for women’s suffrage with Mill, she wrote to her friend Lady Amberley,

Politically one cannot too much detest Catholicism but socially and personally I must admit that many of the nicest people I have known have been Catholics. There is so much that is exquisitely beautiful and touching in Catholicism that I never think anyone quite safe from becoming a Catholic.

The scholar Timothy Larsen has traced Helen’s religious knowledge to some of the letters she wrote on Mill’s behalf:

In a letter ostensibly from John Stuart Mill… one reads, “The true humiliation is when honorable men become in the words of the Psalm, ‘emulous of evil doers.’” The editors of The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill comment that this is “an inaccurate quotation from Ps. 37: l.” It is not, however, a misquotation from the Authorized Version but rather an accurate quotation from the Roman Catholic Douai-Rheims translation. This reveals, in fact, yet another trace of Helen’s deep immersion in Catholic devotional resources.

In 1865, when Helen was thirty-four, had been working with Mill for seven years, and was about to start on the campaign for women’s suffrage, her close friend Lady Amberly wrote that Thomas à Kempis’s Imitation of Christ was still Helen’s favourite book. And according to Charles Eliot Norton, her words had “an oracular value” to Mill.

At the end of his life, in the early 1870s, Mill wrote an essay on religion where he became much more favourable towards religious belief. Timothy Larsen has shown that the image of Mill growing up as purely secular is a little misleading: his father was secular, but his mother was a Christian. Mill’s sister Clara married a member of a Calvinist sect in Plymouth. Mill seems to have been strongly influenced by Helen: she disliked the Catholic church for its political consequences, but retained a faith throughout her life, was buried in an Anglican service, and is rumoured to have converted to Catholicism in old age. Mary’s diary records Helen going to church.

There was something religious about Mill and Helen’s devotion to their cause and the spirit in which they pursued it. Helen was not just a zealous, political person: she was a devotional one.

The anonymous admirer

What makes Mary’s diary so sad, is that all of this part of Helen has vanished. Helen suddenly reappears, no longer the young woman obsessed with Shakespeare, or desperate to go to Mass twice a day, no longer the young actress visiting theatres multiple times a day in search of work, no longer the esteemed editor, no longer the woman so many other women campaigning for the vote looked to, no longer the woman John Stuart Mill called his equal.

Now she is paranoid, fearful, worried about robbers, in a state of perplexity and befuddlement. She is at silent war with her servants and having rancorous disagreements with her niece. Trapped in her old house, with no more philosophers to talk to, no beloved mama who she could barely live without in her early twenties—her letters are full of painful entreaties for Harriet to visit her in Newcastle where she acted—trapped with no campaigning work, no great minds to collaborate with, Helen seems lost to the ghosts of her past. She seems like a ghost of herself.

A recovery begins when Mary gets Helen settled in England. “Her fears have nothing to feed on,” she writes, pleased that her aunt can now sleep through the night, not panic about passing lights or stray noises. Every evening, they take carriage rides to see the lights at Torquay. Sometimes they go in the motor-omnibus. Helen enjoys riding in a trailer behind Mary’s cycle. Helen retains her beliefs, though. Mary gets a pet parrot, who is playful and affectionate. Helen, who long believed it was cruel to keep birds in cages, can only say he is “a poor unhappy prisoner.”

And then comes a glimpse of Helen’s earlier life. One day, an unknown local man dropped off a bouquet of roses for Helen, cut from his garden. The reason was that he was an admirer of J.S. Mill’s writings, and knew Helen to be his collaborator. Shortly after that, Mary’s diary breaks off mid-sentence. It is a fitting image to end Helen’s life, remembered by a neighbour for her admirable work that improved so many lives with its religious devotion to good causes and good living.

I was glued to this. Finding contentment in one's final years, from what I've witnessed, is painfully difficult especially when there are complications from severe mental decline. Helen had her devotional mode, and faith, like a northstar, to guide her. Whether merely temperamental, or hard earned, this seems like something she created for herself to come back to when she needed it most. Or was it the change of scenery? That can be powerful too!

Very Mrs Jellyby.