I take to-day a wife, and my election

Is led on in the conduct of my will;

My will enkindled by mine eyes and ears,

Two traded pilots ’twixt the dangerous shores

Of will and judgment: how may I avoid,

Although my will distaste what it elected,

The wife I chose? there can be no evasion

To blench from this and to stand firm by honour:

We turn not back the silks upon the merchant,

When we have soil’d them, nor the remainder viands

We do not throw in unrespective sieve,

Because we now are full.

That’s Troilus talking at the Trojan council in Act II Scene II (so often a decisive point in Shakespeare: Hamlet and Polonius walking, the balcony scene, Malvolio returning the ring to Viola, Antony agreeing to marry Octavia, the Gadshill robbery, Don John’s plot). He is trying to persuade Paris that the honourable course is not to return Helen to the Greeks, but to fight for her.

He is hypothesising. His words mean something like this: if I take a wife, my choice is governed by my will, my will is governed by my eyes and ears, which have to navigate between impulse and judgement; if I end up disliking her, I am stuck. You don’t send back silks once you buy them from a merchant.

Obviously misogynistic and transactional, what is dramatically interesting about this speech is the way it foreshadows what Troilus actually does to Cressida. He argues that both the man and the woman’s feelings have to be subordinated to honour. When Cressida betrays him, that’s exactly what happens.

And we might think that Troilus betrays her first.

As soon as Troilus has slept with Cressida, he tries to leave. Cressida had earlier warned herself to “hold off” in order to keep his interest and now says, ruefully, “O foolish Cressid! I might have still held off,/ And then you would have tarried.”

Any doubts we have about Troilus as a lover must be intensified by his reaction to the news that Cressida is to be traded to the Greeks. He says “how my achievements mock me.” His speech to the Trojan council was too successful! Helen is not traded; honour is kept; Cressida must go to her father (who defected to the Greeks). Troilus chose war, so now he must lose love.

But note that his “achievement” was a speech about how men lose interest in the women they choose for themselves—and that he is now trying to leave. “Are you a-weary of me?” Cressida asks.

Troilus expresses only a muted regret at the news of Cressida being sent away. Compare her defiant grief, expressed to Pandarus.

I will not, uncle: I have forgot my father;

I know no touch of consanguinity;

No kin, no love, no blood, no soul so near me

As the sweet Troilus. O you gods divine!

Make Cressid's name the very crown of falsehood,

If ever she leave Troilus! Time, force, and death,

Do to this body what extremes you can;

But the strong base and building of my love

Is as the very centre of the earth,

Drawing all things to it. I'll go in and weep—

Next a parallel is draw between Troilus and Paris. Talking, briefly, of the planned exchange, they say,

Troilus: …when I deliver her,

Think it an altar, and thy brother Troilus

A priest there offering to it his own heart.

ExitParis: I know what ’tis to love;

And would, as I shall pity, I could help!

Paris argued at the council for keeping Helen and Priam told him “Paris, you speak

Like one besotted on your sweet delights”. He argued that “Well may we fight for her whom, we know well,/ The world's large spaces cannot parallel.” Clearly, this does not extend to Cressida.

What is clear is that Cressida sees love as love; Paris and Troilus see love as part of honour, or as inextricable from honour. Compared to Cressida, these men seem so insipid. They don’t even come close to her deep feelings.

Why tell you me of moderation?

The grief is fine, full, perfect, that I taste,

And violenteth in a sense as strong

As that which causeth it: how can I moderate it?

There is no council of honour for Cressida. But there is a moment when she realises that Troilus does not feel the same way as she does.

C: I must then to the Grecians?

T: No remedy.

C: A woful Cressid ’mongst the merry Greeks!

When shall we see again?T: Hear me, my love: be thou but true of heart,—

C: I true! how now! what wicked deem is this?

Rene Girard says in Theatre of Envy, that this is a crucial moment. Look at the phrase “merry Greeks”. Cressida used that once before. When Pandarus was trying to persuade her how attractive Troilus was he tells her Helen might even prefer Troilus to Paris. Cressida replies, “Then she’s a merry Greek indeed.”

Why would she suddenly use such a provocative statement to Troilus, causing him to worry about the implications?

Because he was trying to get away. Because he wouldn’t tarry. Because, Girard says, she knew that unless she pricks his jealousy, he won’t be attracted to her anymore. Before Cressida commits a physical betrayal, that is, Troilus committed a spiritual one.

Cressida knows that desire (Girard would say) is a form of envy. People in this play have to be told that, for example, Helen finds Troilus attractive before they find him attractive. Just as Ulysses’ famous speech is all about the emulation problem among the Greek ranks, the romantic plot is premised on emulation too. Troilus was trying to get out — as soon as Cressida mentions the “merry Greeks” he is jealous. Emulation takes hold of him, disguised as love. It is not that he wants her, but that he wants to have her rather than leave her to the Greeks.

Hence her dropping hints about “merry Greeks” to entice him—and her outrage that he thinks she will play false. And indeed, Troilus’s explanation for why he told Cressida to be “true” is weak.

I speak not ‘be thou true,’ as fearing thee,

For I will throw my glove to Death himself,

That there’s no maculation in thy heart:

But ‘be thou true,’ say I, to fashion in

My sequent protestation; be thou true,

And I will see thee.

And yet a few lines later he says again “But yet be true.” She really worried him with that merry Greeks comment! Troilus pretty well exposes himself as loving not for its own sake but as part of a system of emulation when he defends this further accusation.

The Grecian youths are full of quality;

They’re loving, well composed with gifts of nature,

Flowing and swelling o'‘r with arts and exercise:

How novelty may move, and parts with person,

Alas, a kind of godly jealousy—

Which, I beseech you, call a virtuous sin—

Makes me afeard.

A kind of godly jealousy makes me afeard. That’s Girard’s point in a nutshell. (Girard himself doesn’t ever make his argument this simply…) Troilus is motivated by envy of the Greeks. He wants her again because they want her. When Troilus sees Cressida with Diomedes, he confronts him: “I charge thee use her well, even for my charge”.

In response, Diomedes reveals the same thing: this is a question of honour, not love.

…when I am hence

I’ll answer to my lust: and know you, lord,

I'll nothing do on charge: to her own worth

She shall be prized; but that you say ‘be’t so,’

I’ll speak it in my spirit and honour, ‘no.’

Diomedes is saying that he will do the opposite in order to preserve his honour. The driving force in all of this is not love but an envy of other people’s status and a jealous guarding of one’s own position.

The Arden editor points out that one reading of the last one-and-a-half lines of this speech are “if you hadn’t told me to be honourable, I wouldn’t have bothered with Cressida”. Just as Troilus lost interest until the “merry Greeks” were mentioned, Diomedes’ interest is pricked by Troilus’s interest. It’s all about emulation, not true love.

It is notable in all of this that Cressida, the one with real feelings, is the only person who has resisted Pandarus and his sordid interferences. Like Juliet, Cressida is a pure and independent spirit brought low by the dark side of her lover. (Girard believed that Shakespeare put all of this in so that while the groundlings would get the play they expected (Cressida was a famous adulteress, so famous that an unfaithful woman might be called a Cressida) the more sophisticated audience would see how experimental and subtle Shakespeare was being.)

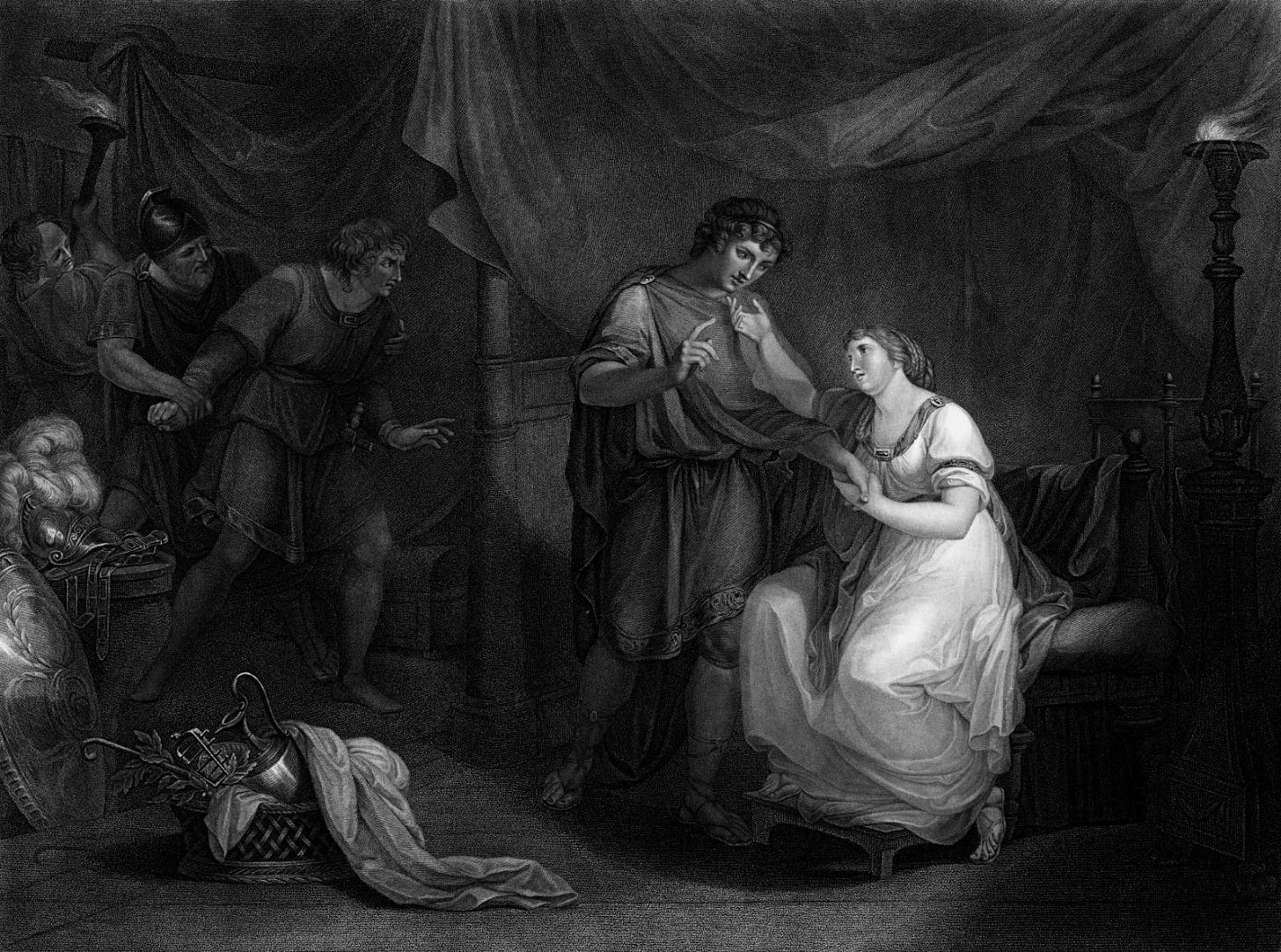

In her final scene, Cressida fetches a token of remembrance for Diomedes. She gives him a sleeve—but immediately regrets it. Here is the scene (with some cuts to make it easier to follow). Notice how, in this generally difficult play, the language is simple, direct, immediate, and unbearably sad for Cressida, who never comes on stage again. She is always at the mercy of some man more concerned with emulation and honour.

C: You look upon that sleeve; behold it well.

He loved me—O false wench!—Give’t me again.D: Whose was't?

C: It is no matter, now I have't again.

I will not meet with you to-morrow night:

I prithee, Diomed, visit me no more.D: I shall have it.

C: What, this?

D: Ay, that.

C: O, all you gods! O pretty, pretty pledge!

Thy master now lies thinking in his bed

Of thee and me, and sighs, and takes my glove,

And gives memorial dainty kisses to it,

As I kiss thee. Nay, do not snatch it from me;

He that takes that doth take my heart withal.D: I had your heart before, this follows it.

C: You shall not have it, Diomed; faith, you shall not;

I'll give you something else.D: I will have this: whose was it?

C: It is no matter.

D: Come, tell me whose it was.

C: Twas one's that loved me better than you will.

But, now you have it, take it.D: Whose was it?

C: By all Diana's waiting-women yond,

And by herself, I will not tell you whose.D: To-morrow will I wear it on my helm,

And grieve his spirit that dares not challenge it.

The irony of Cressida thinking Troilus is “thinking in his bed/ Of thee and me, and sighs, and takes my glove,/ And gives memorial dainty kisses to it” is made all the worse when we hear what Troilus says next.

Wert thou the devil, and worest it on thy horn,

It should be challenged.

He cares more about his honour against Diomedes than about Cressida’s obvious grief at her enforced betrayal. This is her tragedy, not his.

Meanwhile, poor Cressida delivers her penultimate lines in the play,

Ay, come—O Jove!—do come—I shall be plagued.

This reflects her language to Pandarus. She has swapped one controlling man for another. And all Troilus cares about is honour, emulation, envy. Whereas he will now speak about the betrayal of women in general (Think: we had mothers), she speaks about him, and then about herself,

Troilus, farewell! one eye yet looks on thee

But with my heart the other eye doth see.

Ah, poor our sex! this fault in us I find,

The error of our eye directs our mind:

What error leads must err; O, then conclude

Minds sway'd by eyes are full of turpitude.

Troilus is never so self-reflective, never so likely to see the turpitude (baseness) in himself. Poor Cressida. It wasn’t her love that brought about the tragedy, but Troilus’s envy and his “spiritual betrayal” in a world of emulation and honour, but not a world of love.

Helen’s line from her scene with Pandarus was more true than any of them realised,

Let thy song be love: this love will undo us all.

O Cressida!