Writing elsewhere

I reviewed Sophie Mackintosh’s new novel Cursed Bread for Prospect this week and wrote for the New Statesman about the way Liz Truss’s ideas about economic growth have made their way into Keir Starmer’s rhetoric.

This is the third post in a series about “Biography and the Art of Living” based on a salon I ran for the Interintellect Thesis festival. Today is the second answer to the question: what makes a good biography? To be satisfying, a biography needs to give some explanation of a person. This is, I think, the area in which biography is weakest as a genre.

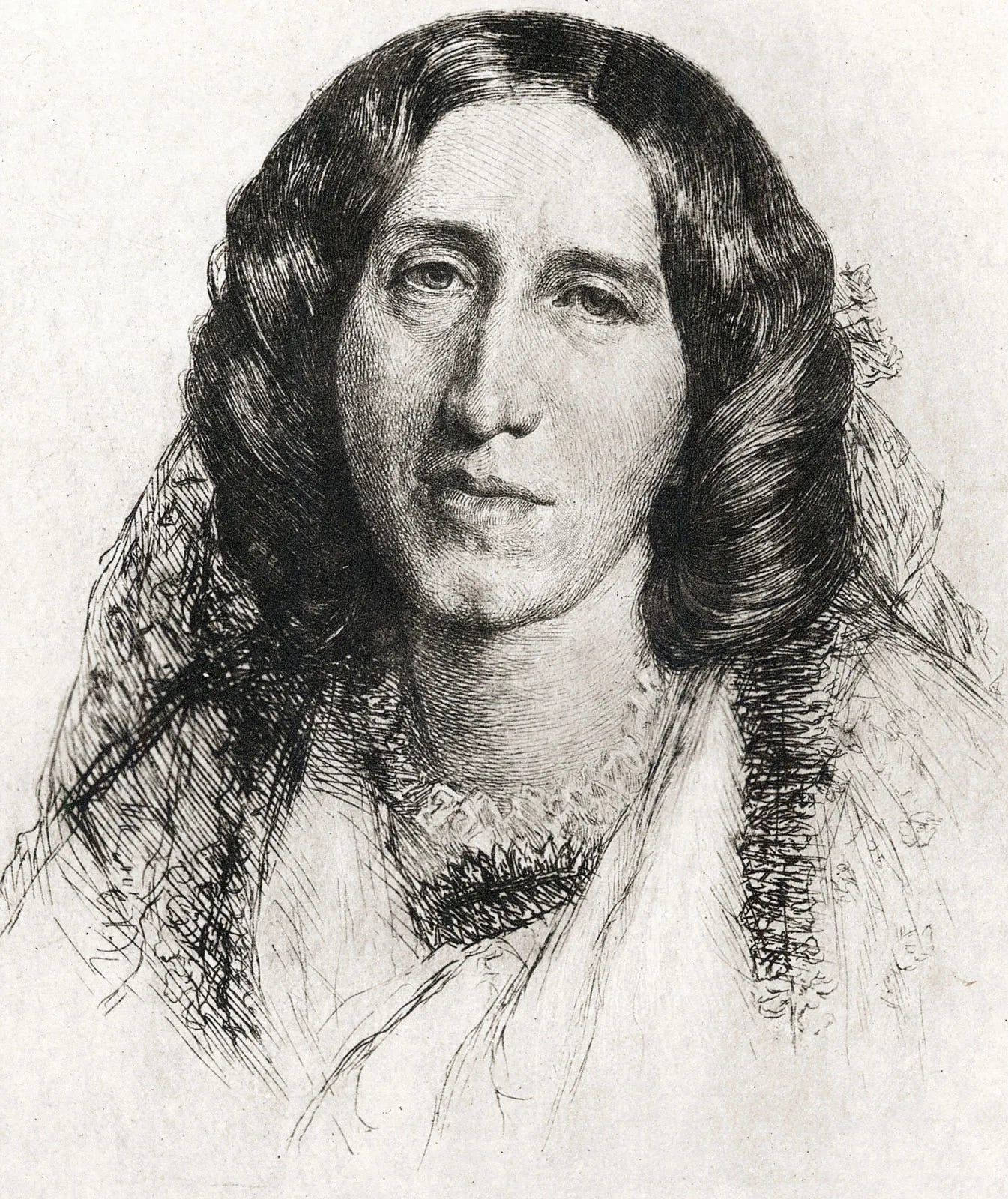

In her essay The Natural History of German Life, George Eliot argued that the ideas of social science ought to be integrated into fiction, otherwise they would be too theoretical, too divorced from the mess of real life, to change anyone’s mind or make any difference. “We need a true conception of the popular character to guide our sympathies rightly,” she wrote, “we need it equally to check our theories, and direct us in their application.”

This is still a gap we have today. Too many books in the Smart Thinking category are what I call “Push the Button” books. They outline a set of findings from psychology or a similar discipline as if these are directly applicable in your life. All you need to do is push the button marked “grit” or “passion” or whatever and you can get the benefit of this magic.

There are two gaps. First, the effect size. The question of how much difference anything in a Dan Pink book, for example, can make is never properly addressed. More importantly, though, is the question of application. What actually happens when network theory operates in a real human life?

One of the things I am trying to experiment with in my book about late bloomers is to integrate social science and biography. So after a chapter discussing network science there is a chapter about Samuel Johnson where I interrupt the narrative to say “Look! Here is the network science we talked about a few pages ago!” In this way I hope to highlight the messy, difficult, uncertain way in which these neat and clean ideas really operate in our lives.

Of course, biographers have done this before. There are shelves full of now-unread Freudian biographies, that gave far too much explanatory power to his theories. But Freud did make biographers pay attention to childhood and the lasting effects of a person’s development on their character. We are now in a position where the new theories of social science need to be better integrated into biographical explanations.

Many historians and scientists will balk at this suggestion. After all, I am advocating for speculation. But we have so many biographies that relate the facts without giving an adequate explanation of them. There is room for more accounts that attempt to see things differently. The risk is that this ends up as a version of the armchair diagnosis problem, where each new generation has a convincing explanation of what disease George III really had.

But if biography is going to be useful as well as entertaining it needs to stimulate more discussion, offer more theories, and cautiously integrate the findings of social science with narrative, as George Eliot advised a hundred-and-sixty-seven years ago.

Subscriptions

Many thanks to those of you who now pay to read The Common Reader. Your generosity is most encouraging. And of course it helps me to keep writing. I am planning some subscriber benefits, the first of which will be a “Biography book club”, where we discuss classic works of biography, ancient or modern. If you would like to be part of that group, or if you are one of the generous readers who wants to support my work, you can subscribe below.

Thanks for reading. If you’re enjoying The Common Reader, let your interesting friends know what you think. Or leave a comment.

If you don’t subscribe to The Common Reader, but you enjoy reading whatever’s interesting, whenever it was written, sign up for free now.