For The Republic of Letters I wrote “the case against George Orwell”—he is “the idol of the higher-middlebrow English-pessimism.” I don’t expect to change anyone’s mind. Those who think of Orwell as a great thinker are hardly liable to rethink their position based on a single essay by me. After all, once you admire a writer for ideological reasons, arguments about their actual capabilities are rather beside the point. Still, it was rather fun. Here’s the opening.

The case against Orwell is simple: he has been over-rated for political reasons. His work is not terrible, but it is by no means the calibre that the admirers believe. Orwell is a grumpy entertainer who some people mistake for an important thinker. All good fun, as long as you don’t take it too seriously.

And this.

The essence of Orwell is, as he once said, the problem of being stuck in one’s class. English people find it very hard to get beyond their class. Down and Out in London and Paris and Wigan Pier are all about Orwell’s own difficulty with getting beyond his class. He wanted to believe in left-wing ideas without being wrenched too far from his natural state. Socialism without marmalade was a socialism too far. And he knew that asking people to change their class habits is dangerous to the revolution. So he trod the line. Technology is inherently disruptive to this idea, so he disliked technology. It’s all downstream of his morning tea.

This leads to Orwell’s fundamental conservatism.

Since discussion of Orwell (rather like Christopher Hitchens) is a blatantly ideological argument rather than a literary one, I made some ideological points, too.

Orwell is beloved by people who don’t want to look at graphs and accept the simple fact that life has become immeasurably better over the last three hundred years.

And.

A real literary genius would either have written superior books or been able to see things more pluralistically. Usually, those two things go together, as with Mill, Naipaul, and all the other writers with whom Orwell ought not to keep company. They could see what he could not: the world is a Faustian pact, not a battle of wits about political allegiances.

How silly to idolise a man who refused to understand all of this because he was self-conscious about having gone to Eton.

You can read the whole thing here.

Why, when Jane Austen wrote Northanger Abbey, was she making fun of the Gothic? Another way to phrase this question is to ask why a young woman in the 1790s—the age of classical learning, Enlightenment ideas, post-Reformation non-superstition; the age of the French Revolution, of modern ideas—was writing about such medieval things?

The Gothic period in art and architecture was the High Middle Ages, starting in the twelfth century. In England, this begins in the time of the Norman kings, running through the start of the modern, at around the time of the Tudors. When the Renaissance began, this style became seen as barbarous, compared to the new classical style.

Walk through England and you will find many fine examples of the Gothic, from Canterbury to Northumberland. Turn right at the entrance of the Victoria & Albert Museum and you step into a work of capitals carved with leaves and the elegant tracery of church windows.

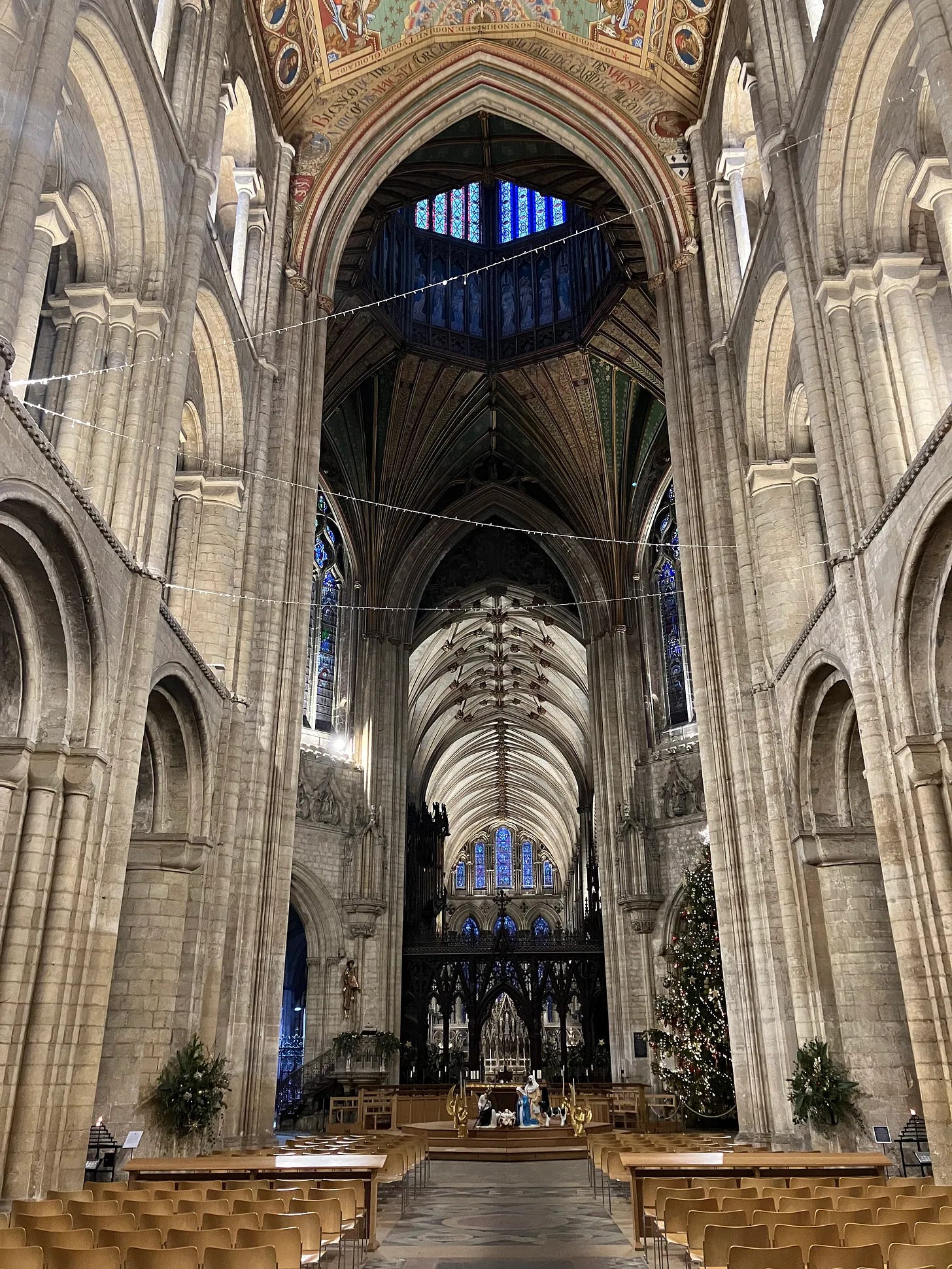

There are several phases of the Gothic: Early, Decorated, Perpendicular. It all depends on the pointed arch. In this picture from Ely Cathedral you can see twelfth-century Romanesque arches in the nave and then, suddenly, pointed Gothic arches at the end. The pointed arch bears more weight, and so it can rise much higher. This is how cathedrals come to look like forests, with their elegant pillars rising like young trees.

Of course, this was not merely a style, but part of a whole ideology. The Gothic is northern, Catholic, devoted. With the Renaissance and the rediscovery of classical knowledge, Gothic was seen as barbarous. Although it had evolved out of the rounded Romanesque style, it was now believed to be inferior to the actually Roman and Greek styles being revived as classical learning moved through Europe with humanism and the Reformation.

In London, you can see this in Covent Garden and on Whitehall, where Inigo Jones, England’s first classical architect, built St. Paul’s Church and Banqueting House. The first has a simple, rugged portico, but exemplifies classical principles of balance, proportion, parallels. It was built in the 1630s, bringing the new Renaissance style to England.

This style was enhanced by Christopher Wren, who rebuilt many of the City churches, and St. Paul’s Cathedral, in the classical mode. Like Jones, he worked from Italian models. The dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral is incomprehensible to the Gothic style. This was a clean, bright, open form of architecture, suitable to the newly Protestant country, where churches needed no mystery, no dark corners at the holy end, but plainness and visibility. In the century following, classical architecture became the basis of the Georgian style—those long rows of clean, simple, elegant houses.

This, too, had an ideology. In the age of science, reason, Enlightenment, and humanism, classical ideas and ideals were more highly valued. The medieval world-view had given way to the modern world view, and the aesthetics had followed.

But, starting with Horace Walpole, the Gothic underwent a significant revival.

Strawberry Hill, Walpole’s house west of London, is a bizarre place. It was built in the 1760s, but it is full of Gothic patterns and pictures—wallpaper with Gothic patterns, and so forth—but it feels very mock, very imitation. It has all the shapes and curves of the medieval, but doesn’t feel at all medieval. As Kenneth Clark says in The Gothic Revival: An Essay in the History of Taste, that is because Walpole didn’t use the right materials. That took several more decades.

When the Gothic revival in architecture was in full flush, in the nineteenth century, this had changed. The Victorians carved neo-Gothic stone and wood all over the country. Parliament looks medieval because it was built at the height of the medieval revival. It is no coincidence that A.W.N Pugin (who assisted Charles Barry) was Catholic, and that England by then (the 1830s) was undergoing a revival of Catholic tendencies in the Anglican church. The new medievalism wasn’t just about style.

Austen comes in the middle of all of this, between Walpole and Barry, between the pseduo-Gothic wallpaper and the Catholic revival. Her contemporary, Walter Scott, did more than anyone for the medieval revival with his historical novels. Ivanhoe is a thrilling re-creation, re-imagining, of the world of Robin Hood and King John, of the days when windows rose in high elegance as the Mass was sung under the drifting incense smoke. In his long poems he used Arthurian themes, which Tennyson later developed in his poems, eventually writing a whole marvellous account of Arthurian myth in The Idylls of the King. By the end of the century, William Morris was making sumptuous Gothic wallpaper, books, fabric, tiles.

So, Northanger Abbey comes in the middle of this fertile period of revival. Austen lived in a world of commerce, common sense, a Protestant dislike of superstition, and a canonical plain style in buildings, sentences, and dresses. But Romanticism was bringing a burgeoning sense of the Gothic back into art. Look at these splendid lines of Keats.

A casement high and triple-arch’d there was,

All garlanded with carven imag’ries

Of fruits, and flowers, and bunches of knot-grass,

And diamonded with panes of quaint device,

Innumerable of stains and splendid dyes,

As are the tiger-moth's deep-damask'd wings;

And in the midst, 'mong thousand heraldries,

And twilight saints, and dim emblazonings,

A shielded scutcheon blush'd with blood of queens and kings.

A perfect description of Gothic architecture. Later on, the appeal of Kate Greenaway’s illustrations was her ability to capture late eighteenth century simplicity at a time of High Victorian Complexity, when “carven imag’ries” were all over even the suburban houses.

In Austen, simplicity clashes with the new medievalism—that is, we see the classic style (plain, balanced, parallel) clash with the Gothic style (intricate, mysterious, romantic). This is the result of Austen teasing and testing her ideas about how novels should work, about the competing morality of the conservative mainstream and the new Romanticism (a huge part of the Gothic revival). It is part of the deeper contrasts in her world, between these two visions of life, religion, and art, which we still see all about us now.