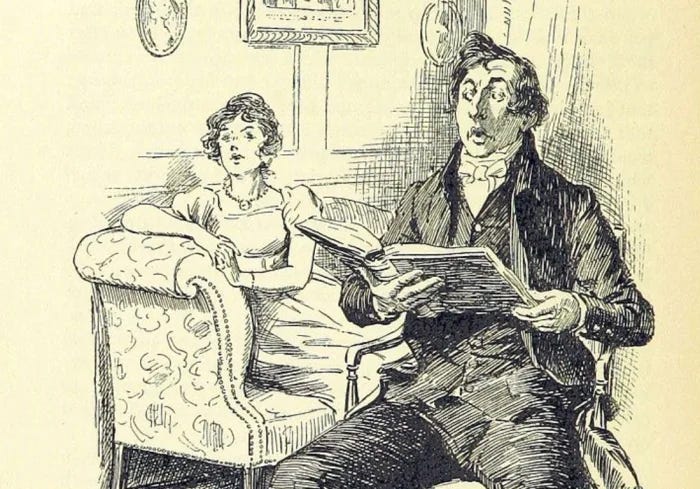

You remember the scene when Mr. Collins is asked to read a novel aloud to the Bennet girls and he is shocked, declaring instead that he brought Fordyce’s Sermons, the full title of which is Sermons to Young Women.

So, the inevitable question: which sermon did he read?

I was perusing Fordyce in the library recently, and it was surely Sermon IV. This sermon deals with the hobby-horse of the age: the immorality of novels. But, perhaps more importantly, it contains some sound common-sense about marriage.

Reading Fordyce is a strange experience when you have Jane Austen in mind. She would surely object to his crabbed and demeaning attitude to proper femininity, which occurs on what feels like every page. No long walks over muddy fields for him!

But who can read this invective against marrying a reformed rake and not feel regret that Lydia did not listen more closely?

That he who has been formerly a rake may after all prove a very tolerable husband, as the world goes, I have said already that I do not dispute. But I would ask, in the next place, is this commonly to be expected? Is there no danger that such a man will be tempted by the power of long habit to return to his old ways; or that the insatiable love of variety, which he has indulged so freely, will some time or other lead him astray from the finest woman in the world? Will not the very idea of a restraint, which he could never brook while single, make him only the more impatient of it when married?

And look at this warning about the folly of wasting your time. Could there be a more suitable passage to read aloud at Longbourn?

If your mornings be spent in rambling and dressing, your evenings in visits and cards, or public entertainments; if this be the general tenor of your transactions, on which side, I beseech you, can the balance be expected to lie at the bottom of the account?

It is when Fordyce inveighs against the reading of Novels that he becomes most Janeite.

(In Sermon VII, by the way, he advocates for women to be readers, just as Lizzie and Darcy do, and in Sermon IV he approves very much of Richardson, Austen’s favourite novelist.) Novels are dangerous. But the old Romances are full of honour and virtue—, much safer reading than novels, which are full of scandal and temptation. That’s because Romances were written in days of higher moral standing.

Alas, Fordyce complains,

The times in which we live are in no danger of adopting a system of romantic virtue. The parents of the present generation, what with selling their sons and daughters in marriage, and what with teaching them by every possible means the glorious principles of Avarice, have contrived pretty effectually to bring down from its former flights that idle, youthful, unprofitable passion, which has for its object personal attractions, in preference to all the wealth of the world. With the successful endeavours of those profoundly politic parents, the levity of dissipation, the vanity of parade, and the fury of gaming, now so prevalent, have concurred to cure completely in the fashionable of both sexes any tendency to mutual fondness.

The Protestant ideal of marriage—the mutual society, help, and comfort, that the one ought to have of the other, both in prosperity and adversity, in Cranmer’s splendid phrasing—is what Fordyce laments being lost with the selling of sons and daughters into marriage, phrasing Austen surely echoes in Emma.

All of a sudden, Fordyce stops sounding like a grumpy old patriarch, and takes on the air of a modern, with all the disdain he can muster for the Mrs. John Dashwoods of this world.

What has a modish young gentleman to do with those antiquated notions of gallantry, that were connected with veneration for female excellence, invincible honour, and unspotted fame? Is it not enough for him, if he intend to strike the matrimonial bargain, that by himself, or an old cunning father, he can drive a good one, to get possession of some woman, whose fortune, joined to his own, if any he have, shall enable him to glitter in public, and in private to gratify other favourite inclinations more freely? Provided these grand points are gained in the person he thus trafficks for to be the partner of his life, what signifies her appearance, her understanding, or her character? And those fine Ladies who seek conquest only for show, too well instructed in the superior consequence of that to put any value on so simple a thing as a Heart, merely for its own sake; what else have they to mind but securing, by whatever arts, such settlements as shall place them, when married, on a level with their companions, or if possible above them, in the all-important articles of gaiety and splendor?

He goes on like this. But doesn’t Fordyce here sound very like Jane!? Of course, there is an irony in that sermon being read to some of the Bennet family, but what a shame that Mr. Collins didn’t take the advice himself to pay more attention to the antiquated notions of gallantry.

This is great!

Always the master of detail, Jane Austen surely knew exactly what she was doing in choosing Fordyce. And many contemporary readers would have enjoyed the joke. Thanks for bringing us into the circle too.